The National Council on Public History (NCPH) defines public history as “the many and diverse ways in which history is put to work in the world.”

To me, the more important definition includes an exploration of who does public history: Public historians come in all shapes and sizes. They call themselves historical consultants, museum professionals, government historians, archivists, oral historians, cultural resource managers, curators, film and media producers, historical interpreters, historic preservationists, policy advisers, local historians, and community activists, among many other job descriptions. All share an interest and commitment to making history relevant and useful in the public sphere.

In that spirit, this year’s NCPH conference convened March 26-29, 2025, in Montréal, Canada, and centered on the theme of Solidarity/Solidarité, echoing historical and contemporary calls for worker solidarity. As NCPH President Denise Meringolo shared, “Solidarity/Solidarité invites us to work together to rediscover our shared heritage and to build new understanding of the beauty and complexity of human experience.”

As program manager for Hopkins Retrospective—the university-wide public history initiative that explores the history of Johns Hopkins University and shares it in meaningful ways—I, along with my colleague Ve’Amber Miller-Dye, Digital Content and Outreach Coordinator for Hopkins Retrospective, had the privilege of speaking on two different panels about our work.

Hearing from other speakers and attendees was also very powerful and memorable. I’d like to highlight a few that I felt were particularly useful for my work with Hopkins Retrospective with regard to outreach, collaboration, and engagement in histories of marginalized people.

Folks from the DC History Conference hosted a workshop titled “Community Connections: Planning an Inclusive Local History Conference.” One of my biggest takeaways was how much time it took to create such a thoughtful, thorough, and welcoming event; they just celebrated their 51st year. Partners, collaborators, friends, neighbors, local historians, and so many different types of people joined in community in the spaces the librarians and archivists provided, which can serve as an example for future Sheridan Libraries events.

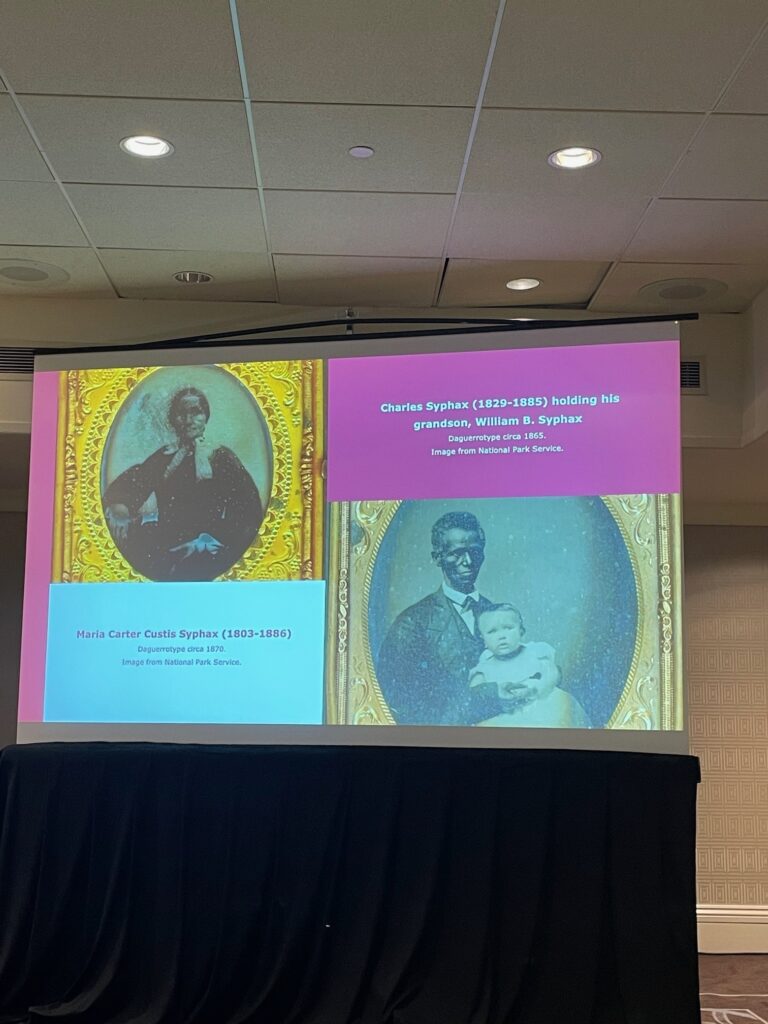

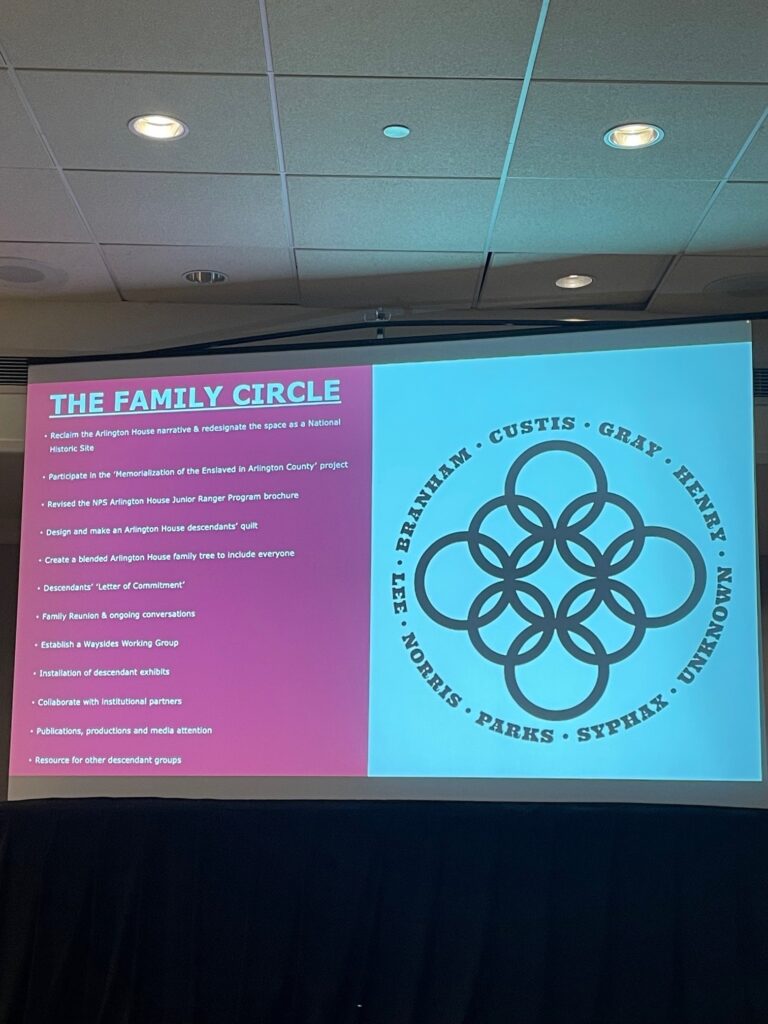

Another panel provided time for a coalition of descendants, genealogists, historians, and National Park Service folks to share their experiences in a session called “Finding Our Voice: The Families of Arlington House.” I found their conversation about developing a “Family Circle” to be very touching. This tool, used by family historians, helps visualize ancestors and descendants of several families within a circle, showing their history is intertwined. It helps document relationships and makes paternal and maternal connections more visible. Their “Family Circle” includes the following families: Custis, Gray, Henry, Branham, Lee, Norris, Parks, Syphax, and an others unknown. The descendants are attempting “to recognize the intertwined historical narratives of the Lees and the enslaved families and reconcile them.” You can read more about their work at NPR and on a petition to re-designate Arlington House as a national historic site.

The conference ended with a plenary to be remembered and felt for years to come. “F*ck Community Engagement, We Work in Solidarity!: Equalizing Collaborations Between Public Historians and Black Stakeholders.” The speakers Marco Robinson, Nishani Frazier, Hilary Green, Christy Hyman, Tara Y. White shared their thoughts, no holds barred.

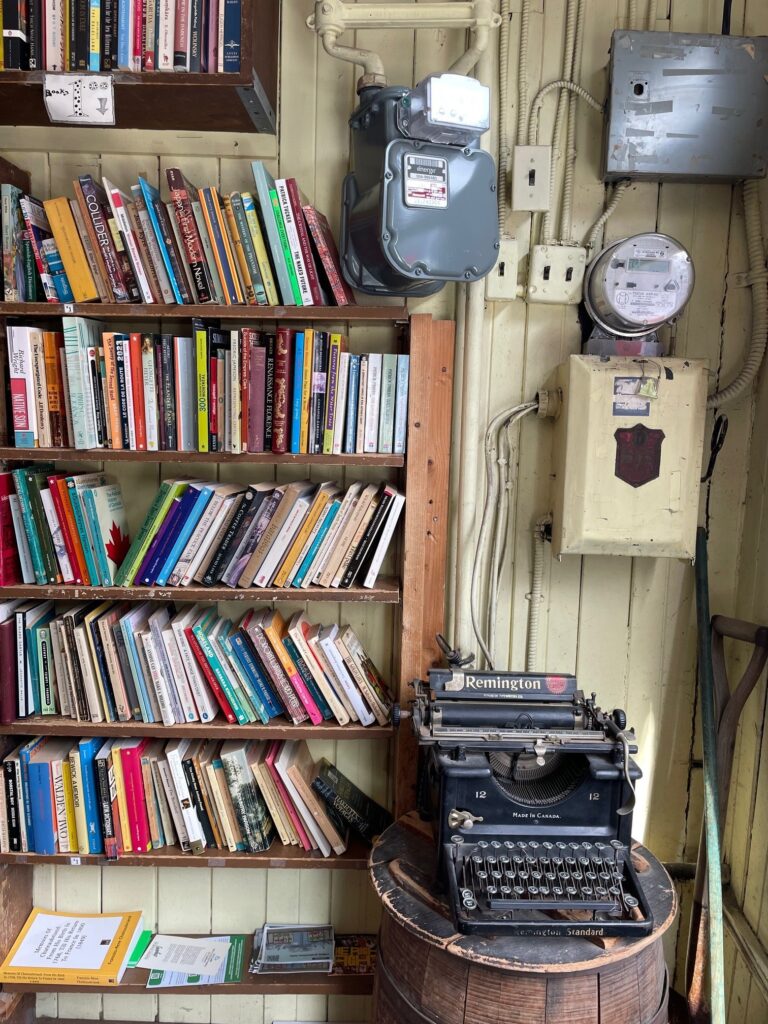

I also seized the opportunity to explore Montreal’s amazing sights, incredible food, and vibrant neighborhoods. As a plant-based eater, I enjoyed tofu poutine and walked the campus of McGill University, where I stumbled upon a 50-year-old used bookstore —The Word— I picked up Willa Cather’s Shadows on the Rock, which seemed particularly appropriate while in Quebec.

Thanks for reading! Stay tuned for Part II featuring Ve’Amber’s takeaways!