Salvete!

Salvete!

My name is Briana Joseph and I am a first year undergraduate double majoring in Neuroscience and Africana Studies. For my Freshman Fellows project I am translating Latin texts from the Renaissance era. The first piece I worked on translating with my mentor, Paul Espinosa, is a series of copperplate engravings by Jacob Hoefnagel (1573-1635), entitled, Archetypa Studiaqe Patris Georgii Hoefnagelii (The Archetypes and Studies of his father, Joris Hoefnagel), published in Frankfurt-am-Main in 1592. These are artistic studies and verses depicting insect and plant life, meant to show off the father and son’s artistic skill and learning. It would later serve as an influential model book for fellow artists.

This work is in the tradition of the Wunderkammer, or Cabinet of Curiosities. These collections held exotic objects set out to display the rarest specimens. As we can see by the amazingly detailed engravings it is almost as if one is staring down into a glass display of life-like wonders.

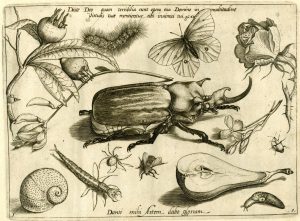

The verses that I translated contain both Biblical passages and learned personal or creative mottoes. For example, the first engraving above has the Latin “Dicite Deo quam terribilia sunt opera tua Domine in multitudine virtutis tuae mentientur tibi inimici tui, an excerpt from Psalm 65: “Say to God: how awe-inspiring are your deeds. Lord, according to the sheer number of your virtue, in like degree will your enemies speak falsely against you.” Located at the center of the plate is a horned or Hercules beetle, a subfamily of the Scarab beetle. According to German tradition, these species of beetle are meant to be a symbolic representation of Christ, as it was thought that it did not reproduce sexually. The inclusion of religious symbols were important to Joris and his son Jacob as they were Calvinists, and thus believed greatly in the sovereignty of God and the word of the Bible. The text at the bottom of the plate makes a great start for a budding artist: “Danti mihi Artem dabo gloriam,” “Since You give me Art, I shall give you glory.”

The verses that I translated contain both Biblical passages and learned personal or creative mottoes. For example, the first engraving above has the Latin “Dicite Deo quam terribilia sunt opera tua Domine in multitudine virtutis tuae mentientur tibi inimici tui, an excerpt from Psalm 65: “Say to God: how awe-inspiring are your deeds. Lord, according to the sheer number of your virtue, in like degree will your enemies speak falsely against you.” Located at the center of the plate is a horned or Hercules beetle, a subfamily of the Scarab beetle. According to German tradition, these species of beetle are meant to be a symbolic representation of Christ, as it was thought that it did not reproduce sexually. The inclusion of religious symbols were important to Joris and his son Jacob as they were Calvinists, and thus believed greatly in the sovereignty of God and the word of the Bible. The text at the bottom of the plate makes a great start for a budding artist: “Danti mihi Artem dabo gloriam,” “Since You give me Art, I shall give you glory.”

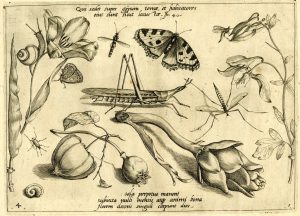

Religion is not the sole reference in these plates. Emblematic dicta are also included, for example, plate 4 reads, “sola perpetuo manent subiecta nulli mentis atque animi bona. Florem decoris singuli carpunt dies,” meaning “only the good things of the mind and of the spirit, subject to none, remain forever. The days seize a flower of its singular beauty.” What intrigued me most about this message was the grammatical construction of that last line. The phrase carpunt dies (The days seize) reminded me of the ancient adage carpe diem (Seize the day!). However, in Joris and Jacob’s reimagining, the day is now the subject of the sentence that performs the action of the verb, and thus expresses the fleeting nature of existence through a slightly more sinister sentiment. The days seize or rob the flower of its beauty: one notices that the lily on the viewer’s left is in bloom, and those on the right closed and beginning to wilt. Interestingly, that small snail in the upper left is the subject of an interesting blog Hunting for Snails – snails in art, which carefully goes through all of Hoefnagel’s 48 engravings and looks to individually identify each of the different snail species. It would be great to match up my future Latin translations with that blogger’s work to see if the texts shed light on the symbolism of the snails.

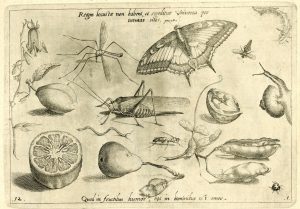

Finally, a nice example of Latin word play can be seen in plate 12 which reads, “Quod in fructibus umor, hoc in hominibus est amor,” meaning “What is the lifeblood in fruits, love serves as the same in humans.” What is most intriguing about this line is the sophisticated word play in the construction of the verse. The words “umor” and “amor,” lifeblood and love, are near homonyms and nicely emphasizes the connection between the two, all while young Jacob learns the tricks of the trade of an artist and the tricks of Latin — quite astonishing really, considering Jacob was all of 17 when he produced this work, himself a worthy Freshman Fellow!

Finally, a nice example of Latin word play can be seen in plate 12 which reads, “Quod in fructibus umor, hoc in hominibus est amor,” meaning “What is the lifeblood in fruits, love serves as the same in humans.” What is most intriguing about this line is the sophisticated word play in the construction of the verse. The words “umor” and “amor,” lifeblood and love, are near homonyms and nicely emphasizes the connection between the two, all while young Jacob learns the tricks of the trade of an artist and the tricks of Latin — quite astonishing really, considering Jacob was all of 17 when he produced this work, himself a worthy Freshman Fellow!