Enjoy this post by Tim Lyu, one of our 2017-2018 Special Collections Freshman Fellows.

In 2016 the Hopkins’ website, said in undisguised pride, “For 37 years in a row, we’ve put more money into research than any other U.S. academic institution.” Honestly, this is precisely what I had in mind as I came across the flyer about Freshman Fellows in a dimly-lit corner of a men’s restroom in the Milton S. Eisenhower Library – the opportunity to conduct humanities research and even get paid for it.

In 2016 the Hopkins’ website, said in undisguised pride, “For 37 years in a row, we’ve put more money into research than any other U.S. academic institution.” Honestly, this is precisely what I had in mind as I came across the flyer about Freshman Fellows in a dimly-lit corner of a men’s restroom in the Milton S. Eisenhower Library – the opportunity to conduct humanities research and even get paid for it.

On a more serious note, however, my interest in independent, literary research traces back to the last semester of my high school career. In my senior spring, I compared and contrasted the literary works (letters, memoirs, novels, etc.) that came out of the Chinese Cultural Revolution to those of the Japanese American internment experience during WWII. By juxtaposing these two historical events, I attempted to illustrate the ways by which multiple languages help victims of history bear the memory of their traumatic experiences. Through this research, I’m more convinced than ever of the resilient power of words to tell stories despite the limits of time, culture and space. Moreover, I started to realize the contemporary significance of literary research, for my own helped me better understand the various forms of public grief – the Black Lives Matter movement, police brutality, and even the recent removal of Confederate statues – we’re experiencing in the U.S. today.

Even more, my unique encounter with the translation between languages as well as cultures primed me for what I plan on accomplishing as a Freshman Fellow. Right now I’m investigating the mysterious Jose Pazos Robles, a professor of Spanish at Johns Hopkins from 1920 to 1936. Unfortunately, Robles was on vacation with his family in Spain at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Although Robles supported and worked for the Spanish Republican Government, or the Loyalists, as an interpreter at the Russian Embassy, he disappeared in 1937. Years later it was learned he had been executed by the Loyalists as an alleged spy for Francisco Franco, leader of the opposing Nationalist forces.

Therefore, my research aspires to demystify the ambiguity surrounding Robles’ death, the chain of unfortunate events leading to it, and its long-lasting repercussions. I started the research through a close-reading of the correspondences available at Special Collections, many of them handwritten by various people of the Hopkins community, members of Robles’ family, and Robles himself.

It has been a real treat to read these letters. Some of them deal with the mundane logistics of Robles’ insurance and unpaid royalties from his publishers, exhibiting the bureaucratic responses of the companies demanding more evidence of Robles’ death. Others showcase the baffled, helpless family of Robles – his wife Margara, his daughter Marguerite, and his son Francisco – in desperate need of financial assistance while still praying for Robles’ return. Regardless of the content, these yellow papers, wrinkled at the edges but alive with wildly cursive handwriting, show a fragment of history that has been forgotten by many but had been lived by a few. From the ink of these Spanish words, some of them crossed out and rewritten, I can almost smell the puzzlement of Marguerite, sitting alone in her apartment in France and waiting for news of her father; the dread and unease of Francisco, fearing for his own destiny, who was later interned as a prisoner of war; and the sincere hope of Hopkins Professor H. C. Lancaster, a colleague and friend of Robles, to help the poor, shocked family of Robles.

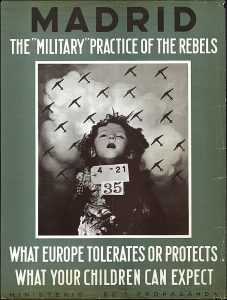

All these details sum up what I’m truly passionate about: to relive the history through primary resources, something I didn’t have access to in high school. And I’d like to design this project, with the help of my mentor Jim Stimpert, so it becomes more than a mere translation from Spanish to English or a case study of Jose Robles alone. Instead, by utilizing secondary resources such as biographies, movies, or even war propaganda posters, I’m hoping to use the story of Robles to shed light on some details of the Spanish Civil War, which served as a historical prelude to the larger conflict between the geopolitical powers of the Communist Soviet and the U.S. during the Cold War. Furthermore, I’d like to examine ways in which the people of Hopkins and Baltimore, including Professor Lancaster, Hopkins President Isaiah Bowman, Professor Esther. J. Crooks of Goucher College, and Baltimore lawyer Emory Niles, had been supporting Robles’ family. More than a story of betrayal, death, and misunderstanding, the mystery of Robles is also a testimony to friendship and solidarity across national boundaries in times of crisis.

While I’m still at the beginning stage of my research, I understand that my goal is definitely subject to change. But what I enjoy the most about the process is not finding the answer but rather the opportunity to follow one question into many others.

_________

Explanation of the “Madrid” poster (above)

This image of a poster became rather famous in the propaganda war between the Loyalists and the Nationalists in Spain in 1936. The child in the center is allegedly a victim of a Nationalist (Franco) bombing attack that took place in Getafe, a town near Madrid. The poster, published by the Loyalists, is trying to show how inhuman the Nationalists were in using indiscriminate bombing of civilians (and children) to further their political aims. It was an effective tool at the time. The back story is that there is at least some doubt as to whether the atrocity in Getafe actually took place. — Jim Stimpert, Senior Reference Archivist, JHU Special Collections.