The volume of our daily digital communications, combined with the relative scarcity of data preservation, mean that many of us face the prospect of losing most of what we have written and shared with others. But is this a new conundrum? No. This has been a serious problem ever since the revolution of ephemeral print culture in the early modern period.

Now the Virginia Fox Stern Center for the History of the Book in the Renaissance is restoring access to a trove of documents from a turbulent time in English history thanks to a recently awarded two-year grant of $318,000 from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The funding will allow the center to create an online database, digital library, and allied scholarly publications that will make publicly accessible a collection of over 5,000 printed broadsides and pamphlets from the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

The database and digital library will rely on materials collected and meticulously annotated by the jurist, parliamentarian, diarist, and long-time Londoner Narcissus Luttrell over a 50-year period (1679-1730). This corpus constitutes the single most extensive collection of its kind in the history of early modern print culture, and has been studied only minimally due to the library’s dispersal at auction in 1786.

Earle Havens, Director of the Stern Center and Nancy H. Hall Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts, and Alvan Bregman, Associate Professor Emeritus at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and an Associate Research Fellow of the Stern Center, will lead the effort, having spent the last 25 years and more reassembling as much of Luttrell’s collection as possible.

“It’s difficult to understate just how rare these materials are,” says Havens. “In many cases the only surviving copy of a given broadside is Luttrell’s copy bearing his telltale annotations. He did more than almost any other figure of the early modern period to gather and preserve printed matter that was literally never intended to be preserved, thus remaining for the most part unbound, vulnerable to damage, and easily discarded.”

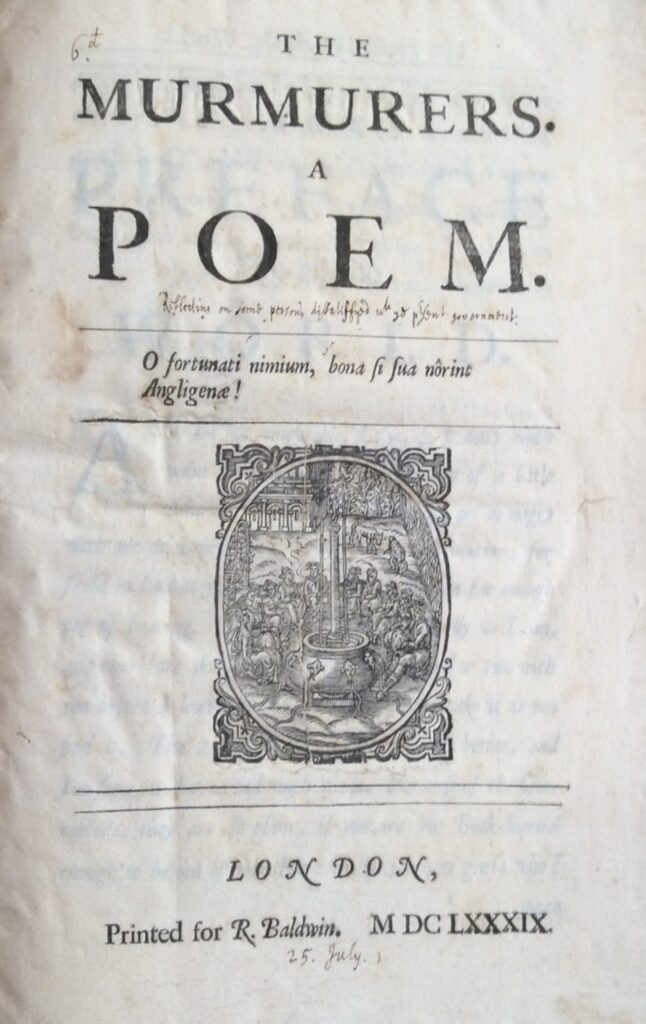

Luttrell’s collection includes contemporary news books and broadside ballads; irreverent “poems on affairs of state;” doleful verse elegies on the deaths of kings and potentates; worrisome prophecies of impending wars; short-form fire-and-brimstone sermon pamphlets; sensational, and often illustrated, broadside reports of portentous earthquakes, floods, plagues, and monstrous births in the countryside—many taken as omens of imminent divine retribution for the presumed iniquities of a sinful nation; sumptuously printed celebratory broadsides marking the ratification of peace treaties; and the single largest extant collection of “frost fair” broadsides—ephemera printed with makeshift presses set up in temporary booths on the river Thames when it had repeatedly frozen over in wintertime.

Havens and Bregman have been collecting and transcribing Luttrell’s marginalia, including precise dates of acquisition, prices paid, and rich bodies of additional interpretive markings since the late 1990s. All of these will be entered into an online searchable database, along with their analysis of the data. They will also explore Luttrell’s diary, replete with references to ephemeral publications, and his manuscript notebooks and commonplace books in which he made frequent reference to broadsides and pamphlets in his collection.

“It is exciting to think of the unrecorded annotations this project will bring to light as Luttrell’s far-flung collection is brought together again after such a long diaspora,” says Bregman. “Hundreds of unrecognized imprints that belonged to Luttrell are still to be found in rare book libraries and museum print collections, and each will add to our understanding of the print and news culture of this dynamic period in history.”

Luttrell’s collection and annotation of ephemeral print was born out of the national crisis of the so-called “Popish Plot,” an invented Catholic conspiracy that threatened to overturn Protestant rule in England between 1678 and 1681. Hatched by a disgruntled minister claiming a widespread Catholic conspiracy to kill the Protestant king of England, Charles II, the propaganda and polarizing scandals associated with the Popish Plot helped precipitate the first two-party political system of Whigs and Tories. Less understood is how this event also helped hatch what would become a continuous and sustained daily “news cycle” printed in ephemeral forms over the ensuing half century, feeding an incessant, daily demand for the latest political developments, gossip, rumors, and popular paranoia surrounding the alleged plot within the burgeoning megalopolis of London.

“Narcissus Luttrell’s library of ephemera uniquely reveals the short-term movements of British politics for fifty years,” says Anthony Grafton, Henry Putnam University Professor Emeritus at Princeton, and a collaborator with Havens on an earlier grant-funded marginalia project, The Archaeology of Reading.

“Narcissus Luttrell’s notes reveal the extraordinarily systematic efforts he made to date, analyze and store them—thus allowing us to follow Britain’s tempestuous politics, move by move, with microscopic precision. This largely forgotten 18th-century ‘information machine’ will come back to life at the Stern Center, and many unique and fascinating pieces of cheap (and sometimes expensive) print will be made accessible to scholars thanks to this project.”

Professor William Sherman, a marginalia scholar and Director of London’s Warburg Institute agrees. “In recent decades, scholars have worked hard to recover the political role played by print in the turbulent years of the English Civil War (1642-51), and nowhere is the extraordinary activity of both authors and readers more powerfully preserved than in the (now scattered) collection of annotated ephemera originally gathered by Narcissus Luttrell. For more than a quarter century, Earle Havens and Alvan Bregman have been building up a comprehensive picture of what Luttrell owned and how he used it, and, thanks to this generous grant from the NEH, he and his colleagues are poised as never before to bring this long-lost library of impossible rarities back to life.”

Havens and Stern Center Postdoctoral Fellow Martin Michalek will highlight selections from the Luttrell collection on October 24 at noon in the free, online talk “The Ephemeral Renaissance: Rare and Unique Single-Sheet Broadsides at the Sheridan Libraries.”