Enjoy this post by Romila Detering, one of our Special Collections First-Year Fellows for the 2024-2025 academic year.

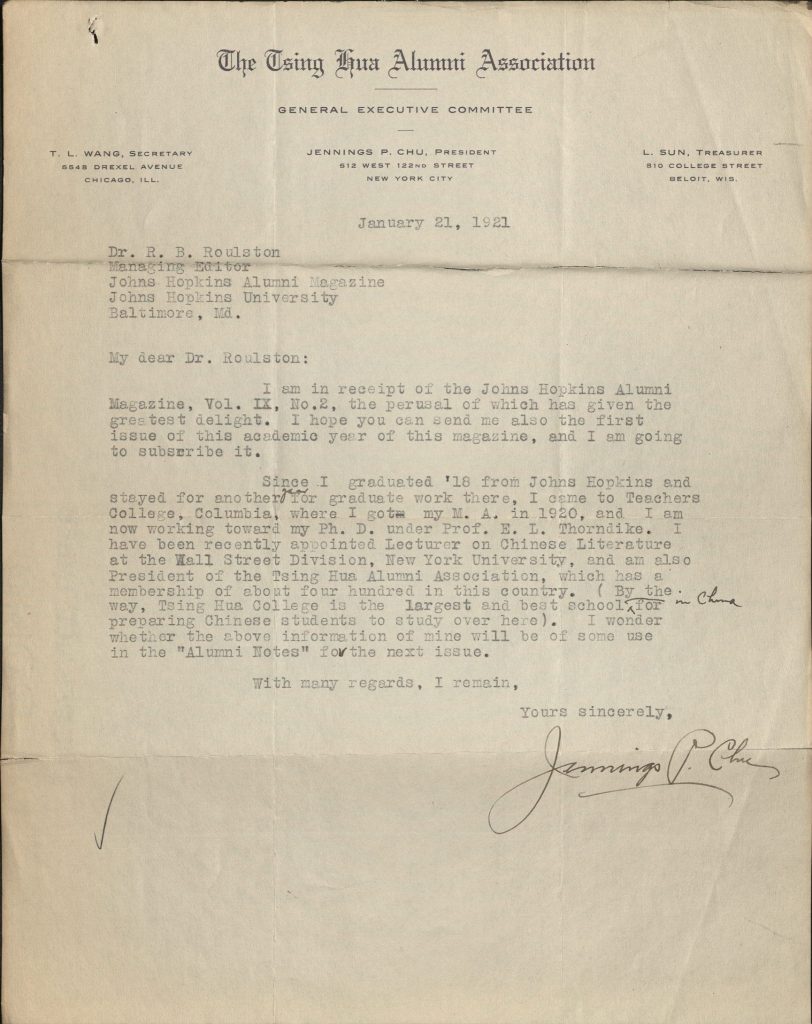

As I paged through the yearbooks from the late 1910s, I gasped at the comments that other students had written about immigrant students. The 1918 yearbook editors had written under Jennings P. Chu (a Chinese international student) that “on closer range [they] found he was human.” Under Ho Chin Chen, another Chinese student, the editors had written that “Ho Chin Chen is not a laundry sign but the name of one of the most likable members of [their] class.” The yearbooks revealed how negative the perception of immigrant students was, even European international students, during the American Progressive Era. Racial stereotypes were baked into the comments in the yearbook, jokingly, but concerning, nonetheless.

My interest in immigration and racism stems from my work with refugees in Germany and the classes I have been taking at JHU on international studies. I am currently in the five-year BA/MA program in international relations and have been primarily interested in European refugee policy. But the perception of immigrants in the United States is also fascinating, especially because of the way integration methods have changed in the last century.

The Progressive Era, between 1900 and the late 1920s, was a period of mass immigration to the United States. Immigrants arrived from Europe and Asia for job prospects that arose from American industrialization. While I studied these immigration trends in my US history course in high school, my class skimmed over young immigrants that came to the United States for education, not immediate employment. I primarily wondered if these international students experienced discrimination in the Johns Hopkins admissions process, as racism against immigrants was prevalent and even violent during this period in America. I hoped to examine whether admissions requirements varied for international and domestic students, and how race factored into admissions decisions.

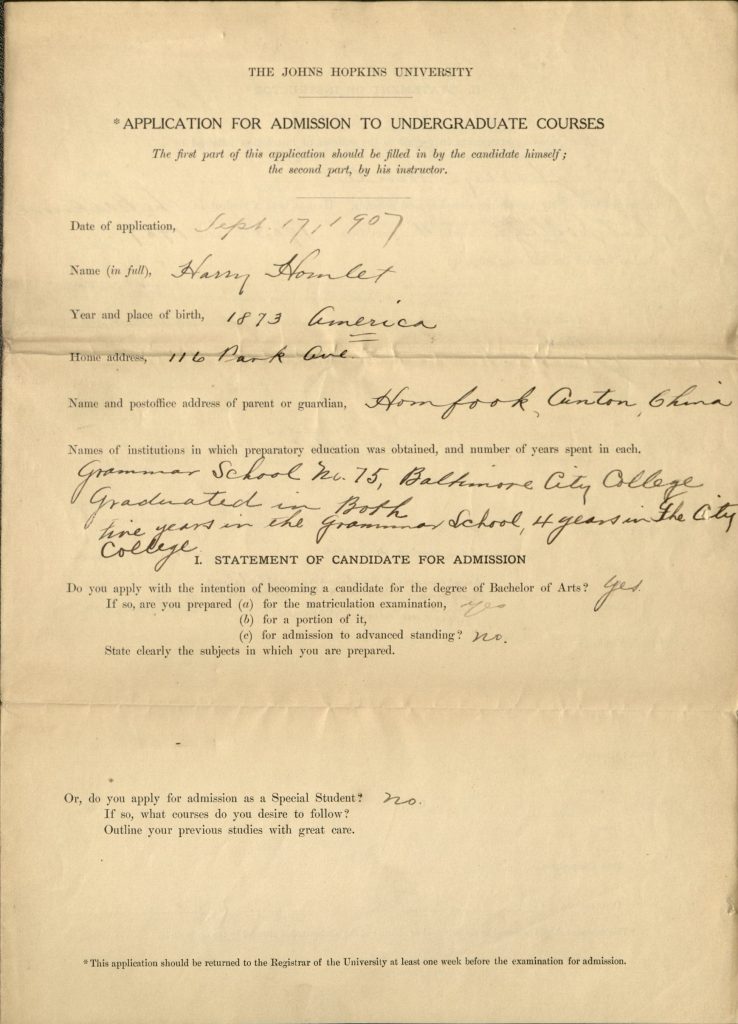

When paging through the early student records of multiple international students, from Italy, China, and Germany, there was a clear lack of discrimination against international students. However, international students were held to high standards (for example, requiring them to understand not only their native language, but also English as the language of instruction and other foreign languages). Some students also found it important to emphasize their ties to the United States in their application. In 1907, Harry Homlet, a student of Chinese descent, wrote “America” under place of birth and underlined it twice.

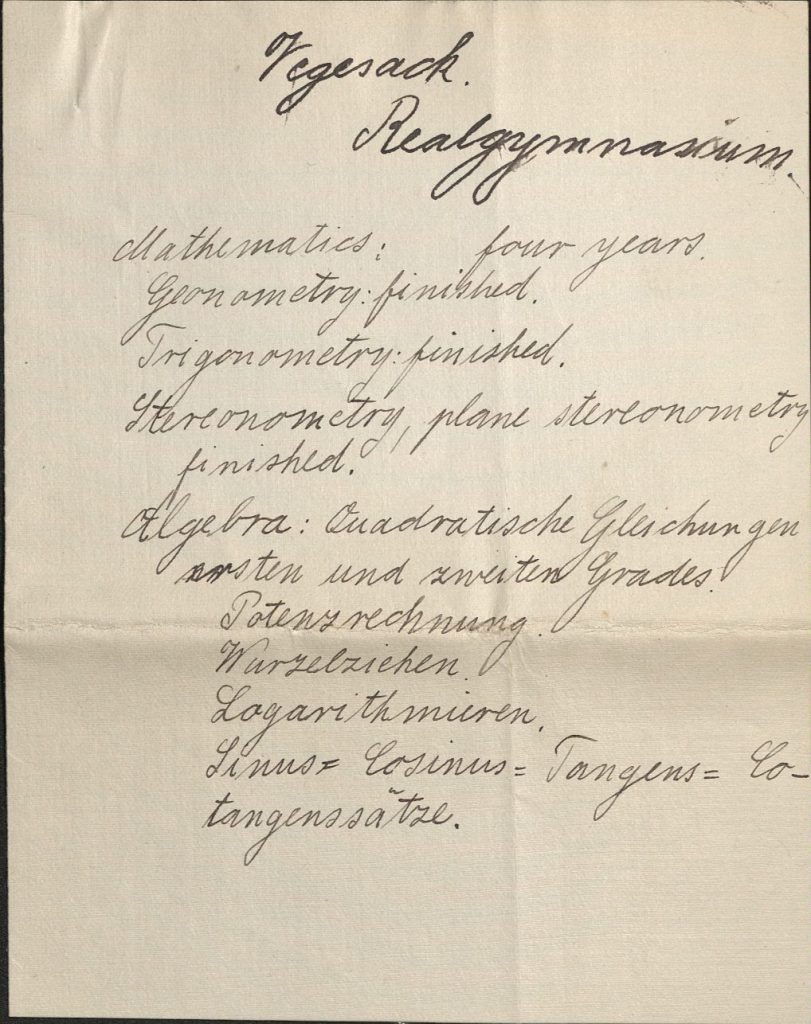

Johann Hinrich Knoop, a German international student, provided application documents in German in his files from 1918. His coursework was half in German and half in English, as he wrote “Mathematics: four years” in English and “Algebra: Quadratische Gleichungen ersten und zweiten Grades” (“Algebra: Quadratic Equations first and second levels) in German. This demonstrated a potential struggle with the English language, although he had studied it extensively along with Latin and French.

While the University did not intentionally cause international applicants to have more difficulty being admitted, setting high language expectations prevented more international students from applying and being accepted. Another student, Jennings P. Chu, wrote to the Johns Hopkins Alumni Magazine in 1921 requesting a copy of the magazine and detailing his post-graduation employment. He stated that he was the President of the Tsing Hua Alumni Association, which he explained was “the largest and best school in China for preparing Chinese students to study over here.” “In China” was handwritten into the margins after the letter had been typed. While this letter was written years after he was accepted to JHU, he recognized the potential lack of understanding JHU had for international colleges and the need to clarify that Tsing Hua was not American. This choice alludes to Chu’s caution, to avoid a misunderstanding of his Americanness, but also Chu’s somewhat cynical perception of JHU.

I am excited to continue examining the applications of international students with Dr. Brooke Shilling and observing how the admissions process responded to the race and nationality of these applicants. I have learned how small details, including an underlined word in an application or a handwritten edit, can highlight how subtly race affected admissions decisions and the Hopkins community in the early twentieth century. I am so grateful to Dr. Shilling for her guidance through my research process and look forward to narrowing down my scope.