Enjoy this post by Virankha Peter, one of our Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2023-2024 academic year.

Interested in applying? Find out about the 2024-2025 program here.

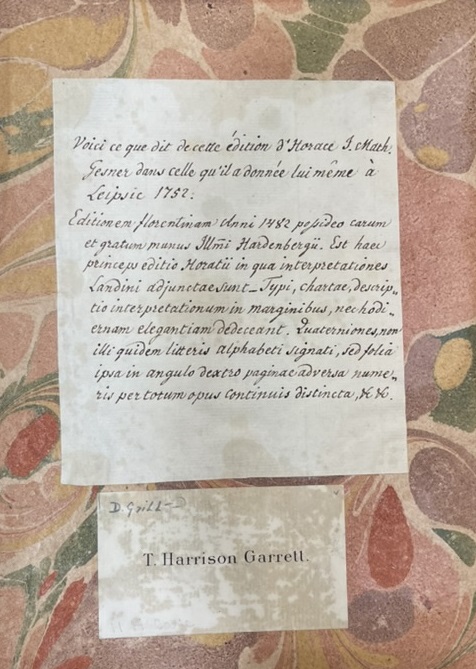

My year with Special Collections was spent understanding the history of a particular edition of a book, Horatii Flacci Opera: Editio Principum Princeps. Florent. 1482. Put plainly, it is a beautiful book of Horace’s Odes featuring commentary from an important scholar of 15th-century Florence named Cristoforo Landino. Critical to my research was a pastedown on the inside front cover. On it was a comment from Johann Matthias Gesner, a German classicist who had much to say about the peculiarities of the incunable I was holding in my hand.

It was this pastedown that I translated. The most interesting line in Gesner’s comment to me was his mention of how “the type, the paper, and the description of the interpretations are in the margins but would not befit today’s elegance.” On its own, the phrase struck me as quite cryptic. I felt a bit like a detective, working to understand all of these little pieces of jargon to begin to form a picture of what Gesner was referring to about this edition. In my investigation, I learned quite a bit about the history of the printed book. Something I loved was the traces of the manuscript tradition (books written by hand) that I learned can still be found in incunables. For example, the book I was examining was printed in Florence. As a result, the typeface being used was Roman, based on the handwriting of Italian humanistic scribes. I knew that this book had been passed down from hand to hand to hand to fall into mine, but it completely changed my perspective that the words themselves – inked on the pages – were like a fossil preserving the handwriting of an older tradition. The Roman typeface I saw in this 1482 incunable connects back to the present, as the Roman typeface inspired the development of Times New Roman which stares right back at me from the screen of my laptop whenever I write an essay.

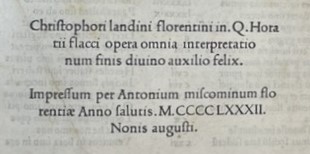

This book was also a relic of the larger tradition of early Italian printing. On the last page of this book, I was delighted to read about the printer of this edition, Antonius Miscominus of Florence, who completed this book on the nones of August (the nones corresponding to the first-quarter moon).

Spending time this semester in the Albert D. Hutzler Reading Room, my work in Special Collections helped me notice the stained glass dedicated to the early printing tradition. I read up on Aldus Manutius, another Italian printer whose printer’s mark – a dolphin wrapping itself around an anchor alluding to the Latin phrase festina lente (“make haste slowly”)– is on display for perceptive eyes. What a different world I couldn’t help now but marvel at, a world where printers put their mark on the books they create, becoming legends we honor centuries later.

However, what about the incunable I was holding in my hand was unusual, as Gesner noted? I felt not only like a translator of language, rendering Gesner’s Latin into understandable English, but a bridge across time. I needed to understand how the book in my hand – already foreign to me, having been printed in a different country at a different time under different conventions – compared to other incunables.

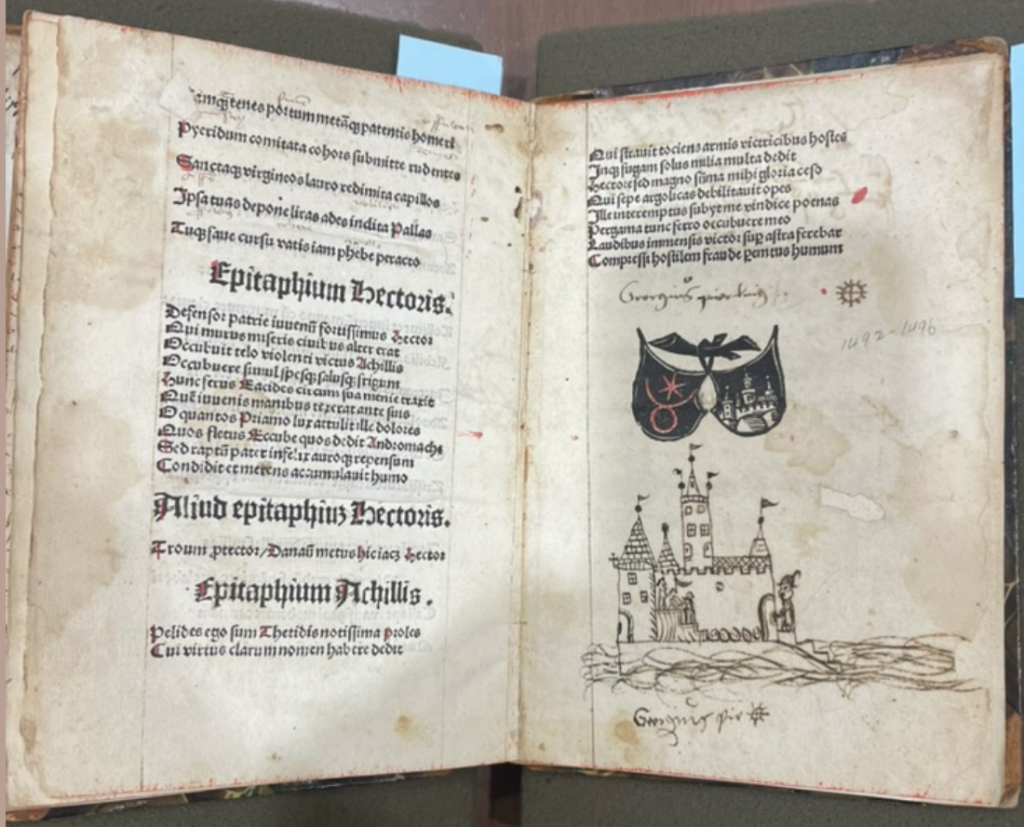

Perusing Special Collections’ incunables in the library catalog online, one caught my eye. It was titled Iliados, printed in 1496 in Frankfurt. I picked it for the same reason I wanted to study the Horace edition. Just as I loved Horace, the Iliad, its translation and reception were something I found incredibly precious. The very title calls up images of heroes and their greatness, gods and their power, fights over honor, and an epic world larger than life. This Iliados was a Latin translation of the text, attributed to Silius Italicus. Gazing upon the Iliados I had called up, I will admit, was surprising. While the Horace incunable from 1482 had been immense, beautifully bound, and in pristine condition, the Iliados I was holding was small. Just larger than my hand, the front and back cover of the book were kept together with the text of the book with a ribbon as the binding had come undone. But opening the book, I was equally surprised at the treasure that awaited me. The little book in my hand had a completely different typeface, Gothic letters with their crooked feet and barbs, as this book was printed in a Germanic city, and covered the center of every page. Filling the margins, rather than printed commentary like with the Horace, were handwritten annotations. Red lines penned by hand marked all the capital letters, a process I learned was called rubrication. Most breathtaking of all, on the very last page of the book, there seemed to be a drawing done in ink and pen.

But my detective work was not done. I still needed to compare this incunable with the one I first studied, looking at the type and the pages, and most specifically the markings denoting gatherings. Gesner notes in the Horace incunable numbers that run continuously through the book. These numbers were not the same as modern page numbers; rather they were printed onto the pages by the printer to help the binder know how to assemble the book. The numbers in the Horace incunable were an unusual way of marking this, while the Iliados in front of me featured the much more common system of letters. I had solved the mystery of what Gesner meant when he described the 1482 edition of Horace as unusual, but by looking at this book with its annotations and drawings I had also unlocked a new mystery, perhaps not one I could solve but one I could wonder at: how beautiful and complex we humans are and the artifacts we leave behind us. In translating the pastedown in the front of Horatii Flacci Opera, I got sucked down the rabbit hole of the history of bibliography, making stops on my journey to understand Renaissance Latin scholarship, paleography, and what it takes to print a book. While I might have always considered myself a lover of reading, this project helped me gain a brand new understanding of the physical entity: the book I hold in my hands and the people it took to get it there.