When artist and theatrical designer Lèon Bakst (Russian, 1866-1924) designed Evergreen Museum & Library’s Bakst Theatre in 1922-23, he did so as a gift to the house’s grande dame, Alice Warder Garrett (1877-1952). Garrett, an enthusiastic if amateur artist herself, wanted to transform a gymnasium on the second floor of Evergreen’s North Wing into a space where she could practice, perform, and host other artists.

After first meeting Bakst in Paris around 1914, Garrett began acting as Bakst’s manager in the United States, coordinating sales of his works among American collectors and arranging for gallery exhibitions of his work.

Then as now, he was renowned for his work as a designer for the Ballets Russes (1909-1929), an avant-garde dance company whose emphasis on a unified production in which the design, performance, and music all were created with each other in mind, Bakst’s art is made up of vibrant colors and patterns.

Garrett also collected Bakst’s art for herself and her purchases today make up Evergreen’s rare collection, which includes everything from hand-painted set backdrops and costume sketches to a Bakst costume worn by Alice and, perhaps most significantly, the Bakst Theatre itself, which is the only extant theater designed by Bakst in the world and one of very few house interiors that Bakst designed.

Because she was both friend and patron to Bakst, he was the natural choice to transform the space. He moved into Evergreen for the winter of 1922-23 and began work, pulling inspiration from traditional Russian folk motifs as well as more unusual inspirations such as cake molds and woven textiles. Such unexpected sources were somewhat par for the course for the eccentric designer, who Alice once wrote about to her sister as “one of the most strange human beings that I have ever know…with such reverence for his art and great will power and concentration on his work.”

For the first time in 10 years, Evergreen has designed a new installation around Bakst’s artwork, incorporating rare objects from the Alice Warder Garrett papers and the Sheridan Libraries collections of sheet music. In celebration, the installation’s curators, Sam Bessen (Eleanor & Lester Levy Family Curator of Sheet Music and Popular Culture) and Michelle Fitzgerald (Curator of Collections for Homewood Museum and Evergreen Museum & Library), have shared some of their favorite artworks that will be included.

Want to see more? Come visit Evergreen Museum & Library on a house tour or view the online companion exhibit to check it out!

Michelle Fitzgerald:

Admittedly, this might be one of my favorite works at Evergreen! Lèon Bakst sketched this backdrop for a scrim to be used in the 1915 Ballets Russes production of Sleeping Beauty. The production would later be produced in London at the Alhambra Theatre in 1921 on a much larger scale where Bakst was able to reincorporate many of these earlier designs. The production was considered a massive design success whose influences are still drawn upon in present-day ballets of Sleeping Beauty (most notably, the American Ballet Theatre’s 2015 tour). I love the dreamlike landscape Bakst creates here that feels simultaneously inviting and eerie. Looking at it, it’s easy to imagine sitting in the audience of the Alhambra after intermission, waiting for the orchestra to start and the dancers to appear on stage.

Bakst designed this costume for an unrealized production of Sadko in Paris. The production’s titular character is a staple in Russian medieval folklore and as such, Bakst drew upon Russian folkloric patterns and costumes to influence his design. As a designer for the Ballets Russes, Bakst was an active participant in the Mir iskusstva or World of Art movement, which was comprised of a group of early 20th century Russian artists who sought aestheticism in all things and a restoration of pre-industrial Russian art, much like the Pre-Raphaelites in England.

Sam Bessen:

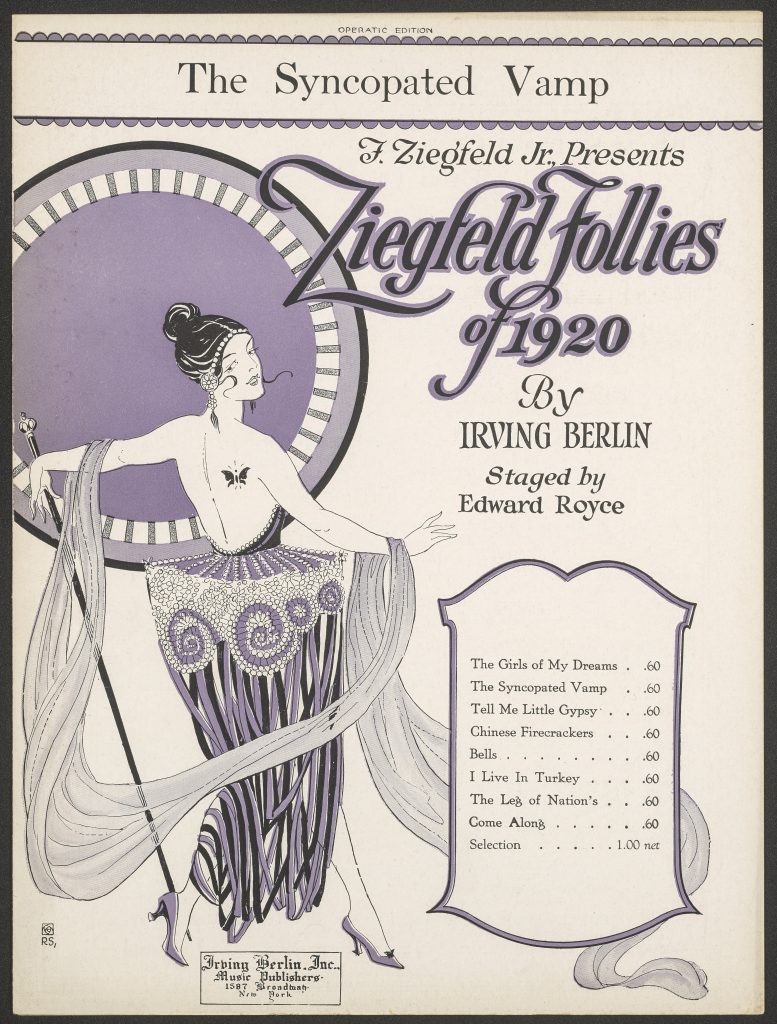

The era of the Ziegfeld Follies is one of my favorites in American stage history. The Follies were a variety show that originally ran from 1907 to 1931, spawning several revivals and films. Imagine a ridiculously over-the-top production with lavish costumes, gigantic ornate sets, and choreography—all set to music by the biggest pop stars of the day. The producer, Florenz Ziegfeld Jr., was inspired by performances he saw at the Folies-Bergère in Paris, a venue that still hosts performances today.

The sheet music now on display at Evergreen demonstrates a few connections between the Follies and the Ballets Russes: they began two years apart (the Follies in 1907; the Ballets Russes in 1909), both arising out of Parisian stage traditions, each bringing together the absolute best in choreography, music, and design. As songs from the Follies were published each year, audience members could take home their favorites to play on the piano.

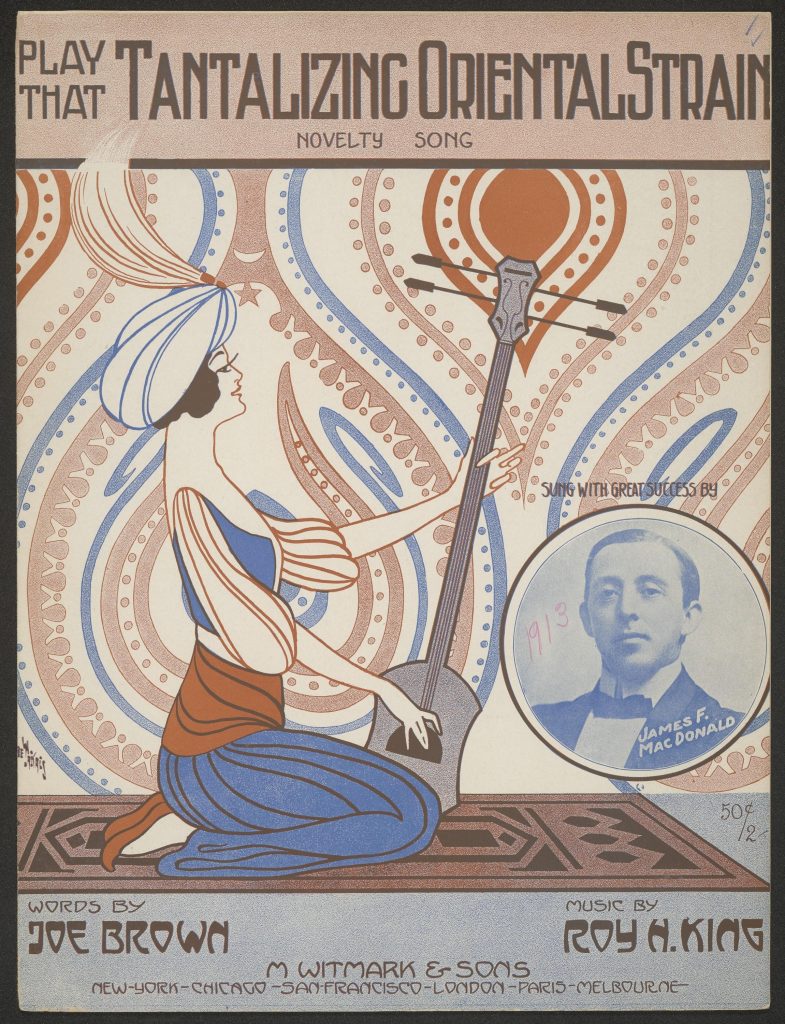

Another focus of the new installation is the spotlight on a recently digitized collection of sheet music covers from the Collection of Middle East-inspired sheet music. These songs were amassed to explore stereotypes of the Middle East and Asia in popular culture from the 18th to the 20th centuries. The collection has been the subject of two First-year Fellows (Vanessa Han and Noel Da) who have explored the exoticized – often sexist and racist—depictions of people, historic sites, and cultures.

In choosing these songs, I wanted to make a connection to Alice Warder Garrett and Lèon Bakst’s fascination with Orientalist designs: Bakst incorporated several such designs into his sets and costumes, and Garrett performed an “Oriental Dance” in Evergreen’s theatre.

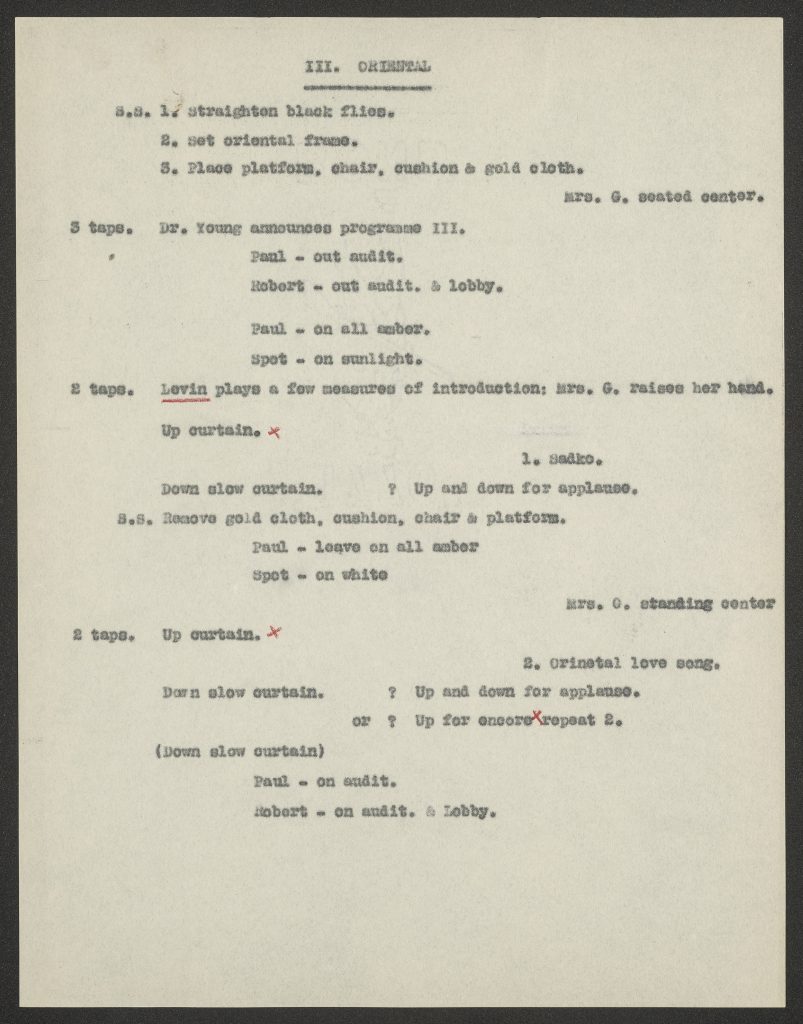

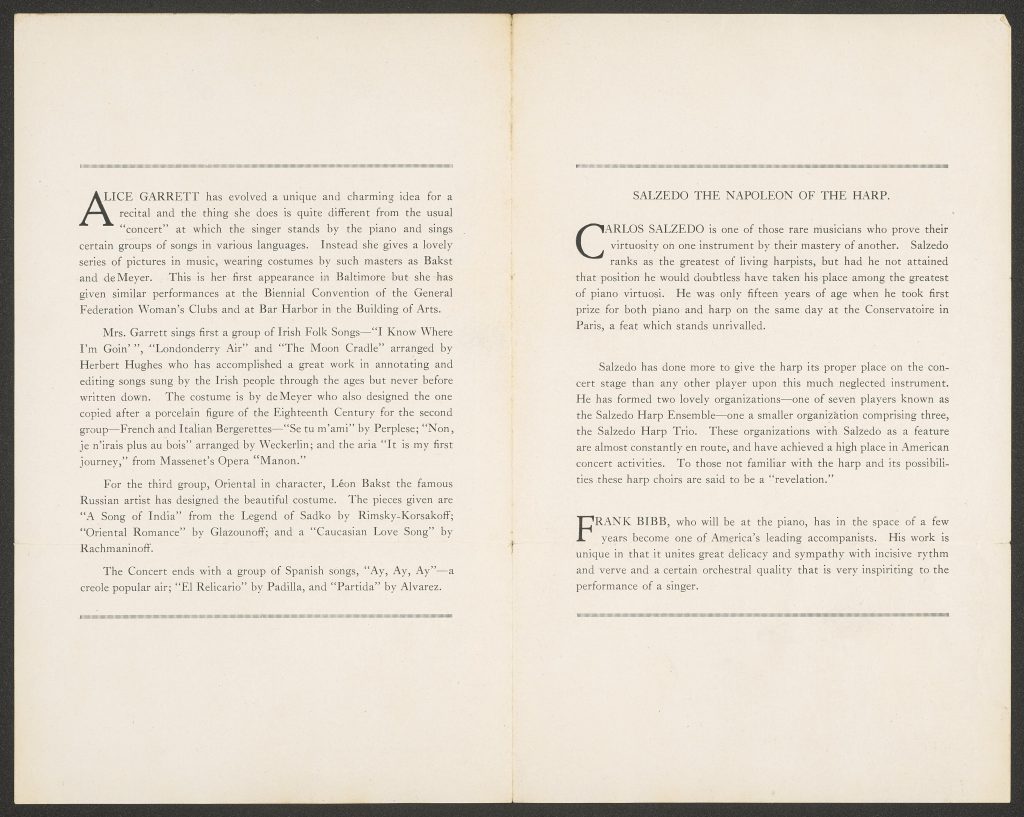

The remaining objects I chose to display come from the Alice Warder Garrett Papers, an archival collection comprising Garrett’s personal papers. In the collection, I found several items that provided me with a deeper understanding of her performance philosophy and creative process. This performance program dives into Garrett’s “unique and charming” approach: “a lovely series of pictures in music.”

Installations at Sheridan Libraries & Museums require the collaboration of many departments. We would especially like to thank the Libraries’ Conservation and Digitization staff for the creation of facsimiles to ensure the long-term preservation of our sheet music and archival collection.