Enjoy this post by Noël Da, one of our Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2023-2024 academic year.

Hello and welcome! Having spent a few weeks parsing through the hazy Middle East-inspired sheet music collection at JHU Special Collections and related research on Egyptomania, here are a few observations I found interesting.

In 1922, Howard Carter broke through the sand and found the first steps to Tutankhamun’s tomb. Over the next months, the magnificence within was revealed to an eager America—a postwar nation, giddy with lavish excess. Fantasies associated with the contents of the tomb took to popular culture with all the sensationalism of a political scandal or bestseller series, with the added benefit of historical truth. Pyramids and palm trees began popping up all over the media (at the time, mostly movies and sheet music), and everyone either wanted to look like Cleopatra or date her.

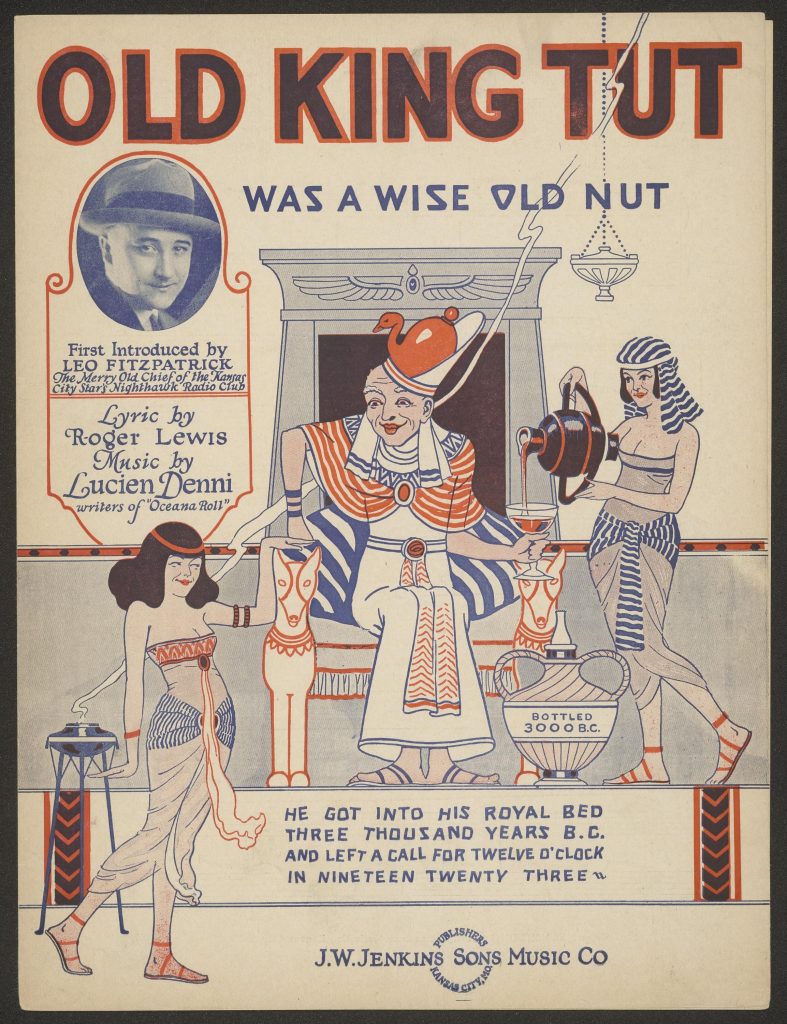

It’s a simple account of the events, and for the most part it’s true. The sheet music I found in the collection dating after the discovery is littered with Egyptian imagery: Sphinxes, hieroglyphic columns, pyramids, and snaking depictions of the Nile. There are even a few that mention Tutankhamun by name:

Even in this cover, we can see some of the more questionable ways in which Egyptian iconography was impressed onto American media. The so-called “wise old nut,” along with the story of how he got into bed in 3000 B.C. only to wake up for viewing purposes in 1923, comes across as decidedly un-Egyptian. Instead, it feels like a set of images forced into the form of an American narrative for the sake of exoticism and marketability. This is a theme that will continue throughout the collection, and it is something else I’ll be exploring—after all, the line between inspiration and appropriation is one that is thin and frequently crossed.

I’d also like to show you some of the ways the tomb discovery narrative does not account for the entirety of Egyptomania in history, specifically by exploring some sumptuously Egyptianized objects and structures that predate 1922. Many of these objects coincided with the Art Deco and Art Nouveau movements, whose elements experienced a great wave of Egyptian influence at this time. This is another thread that I’d like to explore: the way in which foreign iconography is introduced and incorporated into artistic movements until they are recognized as intrinsic to the movement itself—in short, how a certain kind of “cross-cultural contamination” can exist in art.

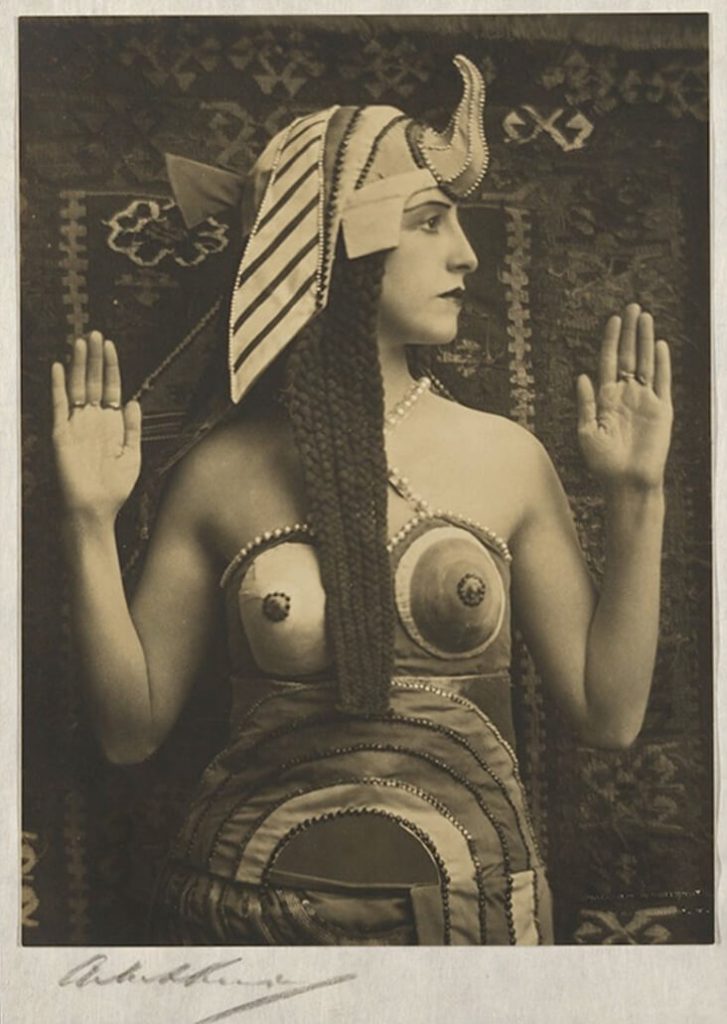

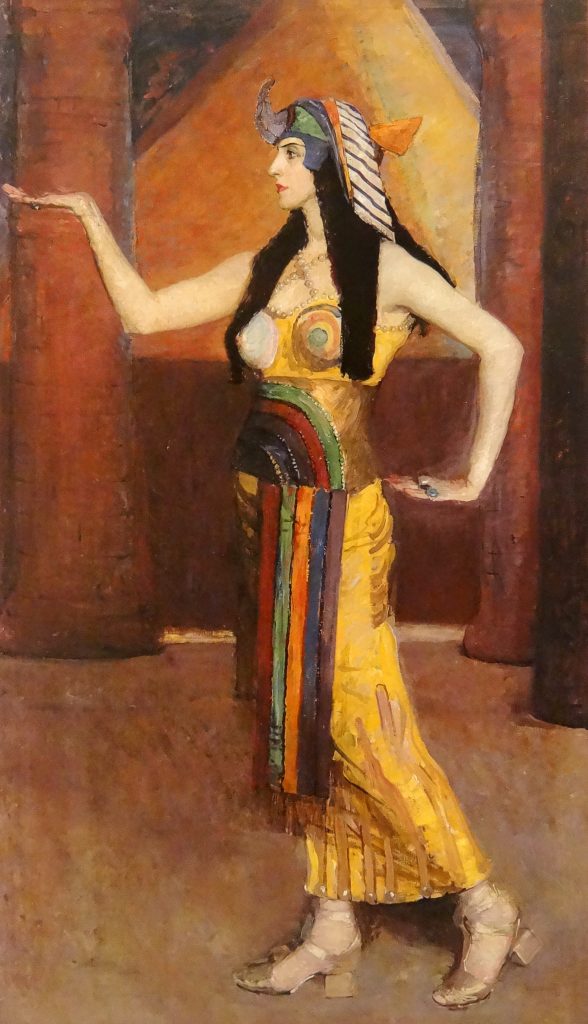

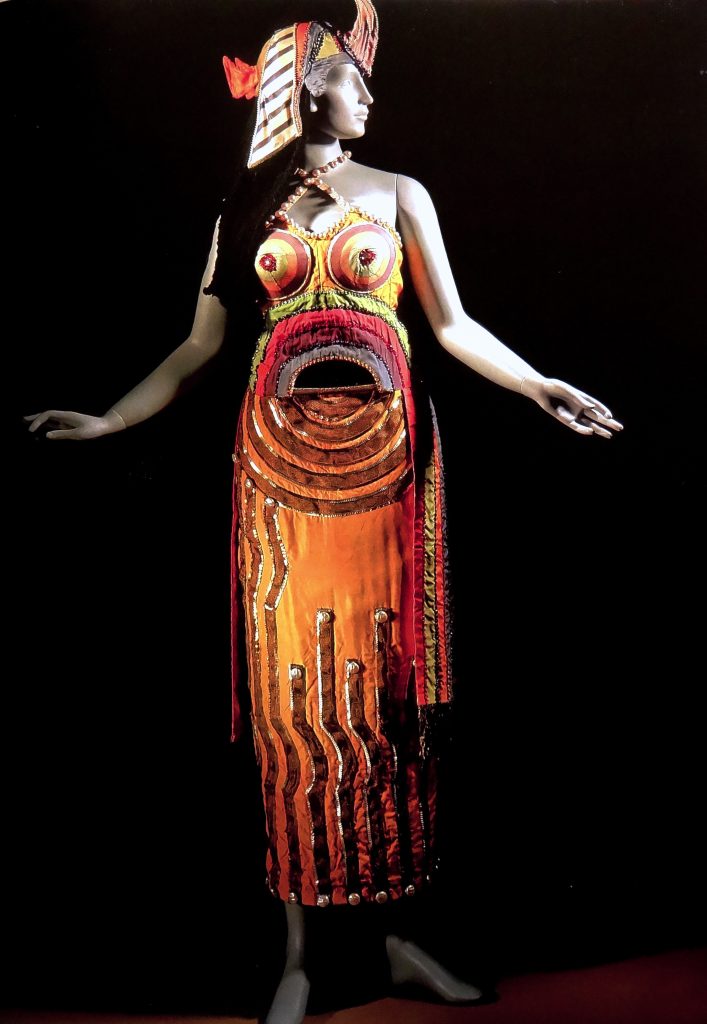

These are images of a costume meant for the role of Cleopatra in a Russian ballet (1918). The designer is Art Deco and Modernist artist Sonia Delaunay. In a blending of cultural styles, the concentric circles of twentieth century Art Deco are filled with the “oriental” colors associated with Egypt. Meanwhile, European textile processes are used to create an Egyptian-looking headdress. The painting (middle) feels especially clashing. European painting styles are used to depict a European model in an “Egyptian” pose with an “Egyptian” costume. Though it may be a beautiful piece of design, there is something jarring about this costume. Whether responsibly or not, it bends the rules of chronological and cultural genre.

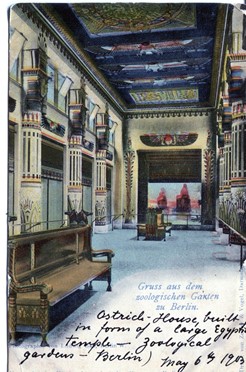

These are images of the Berlin zoo’s ostrich house, built in the 1870’s. The architects, Heinrich Kayser and Karl von Grossheim, dedicated at least some study to Egyptian designs in their construction [James Stevens Curl. The Egyptian Revival: Ancient Egypt as the Inspiration for Design Motifs in the West. 371]. This is apparent from their use of authentic Egyptian images like the Zodiac of Dendera and the painting of the Colossi at Memnon (visible at the far end of the interior room). What knowledge they had, however, may not have been extensive and mostly based on descriptions, like those brought back from Napoleon’s Egypt campaign between 1798 and 1802. This leads to small inauthenticities in the recreation: perhaps the scale is off, or the choice of materials. There is, once again, something recognizably European about this structure.

The same can be said of the Strasbourg “Egypt House.” Again, there is a clash between Egyptian imagery—bright blue and golden colors, hieroglyphic symbols, chevron carvings, reed depictions—and the symmetry and intricacy of Art Nouveau designs. The latter element is best seen in the central panel, whose lines are distinctly fluid and geometric in classic Art Nouveau style. Much like a remix of a song, this structure attempts to blend two separate aesthetics, both vying for visibility.

The next thing I noticed in the collection was the prevalence of a certain kind of word in the sheet music titles. First, there was “girl”: Bedouin Girl, My Cleopatra Girl, My Sumurun Girl: One-Step, My Oriental Girl (and, very similarly, That Oriental Girl of Mine). There was also “lady”: Lady of the Nile, My Lotus Lady, My Lady of the Nile. Then, there was “love”: Love in the Desert, An Egyptian Love Song, The Arab Lover to His Mistress, My Persian Love, My Cairo Love, My Hula-Hula Love. This is not an uncommon phenomenon—with each cultural fad comes an impossibly seductive, typically misogynist idea of a perfect woman to accompany the exotic romance. There were also an awful lot of “My”s in those titles, suggesting an attitude of ownership over the women of this trope. This had been the case for many cultures long before 1920s Egyptomania—recall Esmerelda in Victor Hugo’s Hunchback of Notre Dame, a beautiful and foreign “gypsy” lady.

For now, though, I’d like to focus on one hyper-romanticized woman: Cleopatra. The name saw a surge in popularity in the early twentieth century and Theda Bara’s 1917 performance (pictured below) further mystified its allure.

In many ways, Cleopatra came to embody the Egyptian temptress. Like the general perception of Egypt, her image is constantly shrouded by a haze of vague exoticism and faraway beauty. Attempts to attain or contain it are futile; it always slips through your fingers. In Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, Antony’s friend Enobarbus tries his hand at describing Cleopatra:

“I will tell you.

The barge she sat in, like a burnish’d throne,

Burn’d on the water: the poop [deck] was beaten gold;

Purple the sails, and so perfumed that

The winds were love-sick with them; the oars were silver,

Which to the tune of flutes kept stroke, and made

The water which they beat to follow faster,

As amorous of their strokes. For her own person,

It beggar’d all description: she did lie

In her pavilion—cloth-of-gold of tissue—

O’er-picturing that Venus where we see

The fancy outwork nature: on each side her

Stood pretty dimpled boys, like smiling Cupids,

With divers-colour’d fans, whose wind did seem

To glow the delicate cheeks which they did cool,

And what they undid did.”

(Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra 2.2 914-928)

This description, written in 1606 and supposedly spoken in 30 BCE, begins constructing the soporific shroud of “perfumed” air, that “cloth-of-gold tissue,” around Cleopatra that would hang around on sheet music centuries later. The settings ring so many bells: golden light, a glittering vessel, the Nile meandering through it all. I bring up Shakespeare here to suggest that Cleopatra, and Egypt by association, has always been enchanting, hot with an exotic glow. What I’m interested in relevant to the sheet music collection is how well artists and composers were able to capture it. I also plan to do some more digging on Cleopatra as the fellowship goes on—though, like Enobarbus said, she truly “beggar’d all description.”

As for the music itself, my general impression is… strange. I learned one of the melodies from the collection Across the Burning Sands on the piano. The song was quite odd. It did not sound Egyptian, and based on the research I’ve done into Arabic maqam music, characterized by a set of 7-note scales and certain rhythmic cycles, it was not Egyptian. For my next blog post, I look forward to sharing more songs and exploring the music theory behind them.

Thank you for reading!

The Johns Hopkins Collection of Middle-East inspired sheet music can be found on JSTOR.