Processing archivists arrange and describe unpublished materials so that researchers can use them effectively and efficiently within Special Collections and Archives at universities, museums, historical societies, and other institutions. Because archivists deal with aggregates of unpublished material of various sizes and formats, this process is often more complicated than cataloging published books, which are generally more consistent (they are discreet, predictable units that all have titles, authors, publishers, places of publication, etc.) Archivists developed professional processing standards over decades and even centuries in order to establish consistency, so that researchers know what to expect when they consult archival materials. Some of these standards, such as provenance (the idea that materials created/donated by the same person or organization should be grouped together as collections, rather than organizing material by subject, for example) and original order (the concept that as much as possible, archivists should maintain records in the order given by the person or organization who created them) are fundamentals that have been the bedrock of archival work in Europe and the United States for the last few centuries. Other standards have changed or have been developed in the last 20, 10, or even 5 years.

As an example, the Society of American Archivists first published Describing Archives: A Content Standard (DACS), a guide that archivists use to determine what notes should be included in a finding aid (or guide) for a collection and what type of information belongs in those notes in 2004. Other standards for archival description existed before DACS, but DACS was published as something new rather than a revision of earlier standards. More recently, in the past 5-10 years, archivists at a variety of institutions have started to codify an evolving set of practices around reparative description and reparative processing, a term used by Kelly Bolding in her 2018 presentation “Reparative Processing: A Case Study in Legacy Archival Description for Racism” to encompass processing standards that center historically underrepresented and marginalized people (particularly Black people) and actively counteract the harm that archivists have done in the past and present. Bolding and several of her fellow archivists who make up the Archives for Black Lives in Philadelphia collective created a set of guidelines, the Anti-Racist Description Resources, to assist others doing this work.

These evolutions in standard practice over time can create a need for archivists to reprocess collections. Reprocessing involves looking back at collections that already have been processed (i.e., they already have a complete finding aid to guide researchers who want to use the collection) to bring them up to current standards of archival practice. Sometimes, this simply involves things like adding new notes to a finding aid or making small adjustments to the information in existing notes. In other cases, it involves extensive reprocessing and redescription within a reparative framework.

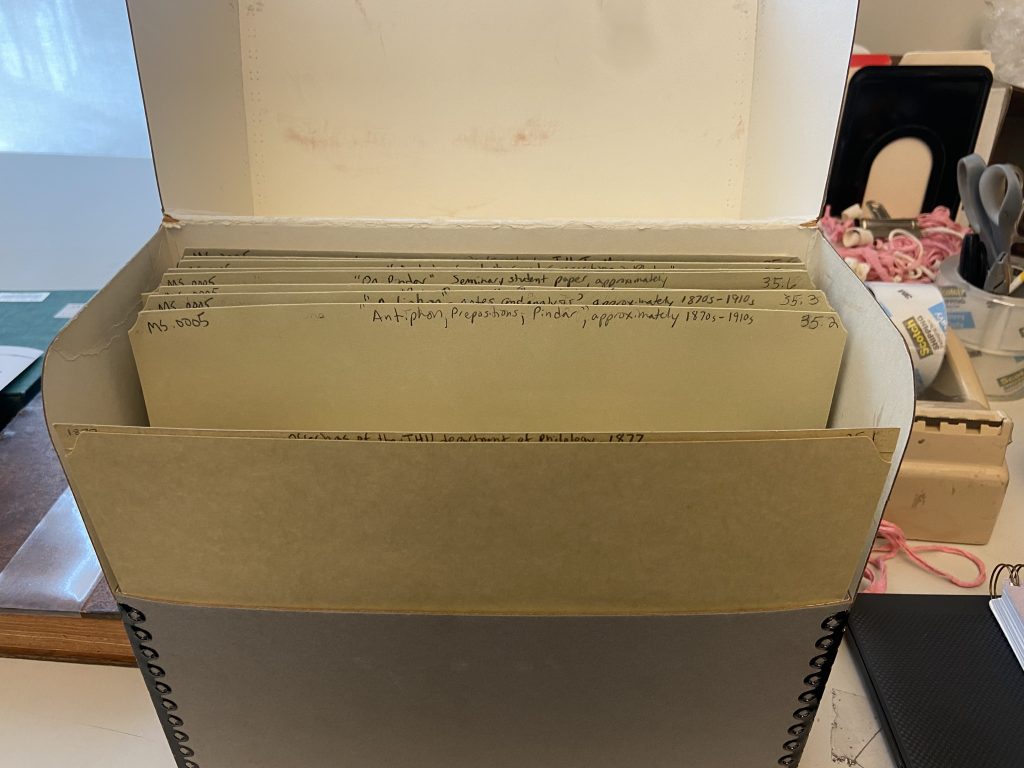

As the Processing and Research Archivist for the Hopkins Retrospective Program, much of my job involves reprocessing collections that are related to Johns Hopkins University’s history. Archivists in Special Collections and Archives processed many collections from the early days of Hopkins in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and our team identified several that would benefit from reprocessing. One of my recent projects involved such a collection, the Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve papers (MS.0005). In the weeks to come, I’ll be publishing additional blog posts about Gildersleeve, the reprocessing project, and the places that taking a reparative lens to the man and his papers took me.