Enjoy this post by Julia Mendes Queiroz, one of our Special Collections Freshman Fellows for the 2021-2022 academic year!

Hello everyone! Welcome to my second, and final, blog post about my Freshman Fellows’ research project “Reading between the Rhumb Lines: Mapping the Caribbean”. This academic year has flown by so quickly, and it’s difficult to believe that I am in the final stage of completing this project. I want to begin by acknowledging and thanking all of the Sheridan Libraries staff who organized the Freshman Fellows initiative this year, particularly my advisor Lena Denis. The guidance and understanding that I received was crucial to the completion of my research, and I am very grateful to have had the opportunity to work with them. Being a Freshman Fellow has been one of the key highlights of my first year at Johns Hopkins.

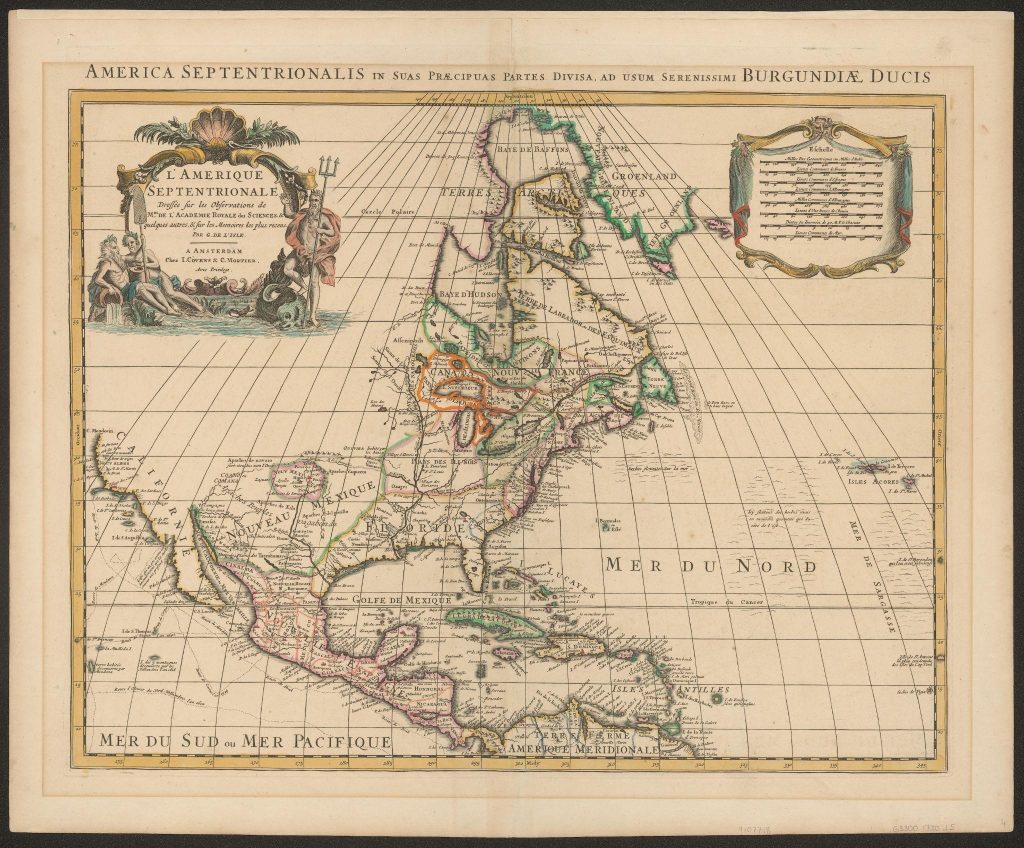

This spring semester, I have continued to interact with the extensive primary material of the Greene Map Collection, studying maps from several different centuries. The following, created in 1730 by a French cartographer, is an illustration of L’Amerique Septentrionale (North America), depicting the coastal United States and Central America:

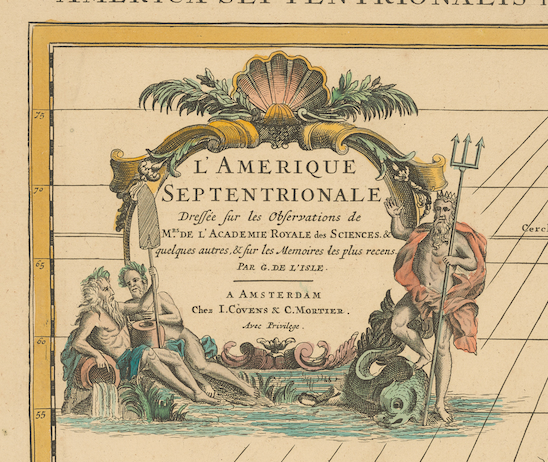

This image is one of the more decorative maps in the collection; the illustration of mythical creatures and ornate structures hint that it was not made to be a navigation resource. The use of color and the type of paper it was printed on indicates that the map was created to feature in an elegant and expensive Atlas, a collectors’ item, as opposed to guiding ships on their voyages. On this specific inscription, the cartographer mentions that this map was drawn upon the observations of the Royal Academy of Sciences and on the most recent ‘memories’, as well as ostentatious displays the scale of the map. In a map intended for navigation, this would be done a lot more simply and practically.

There are several other intriguing details on this map, such as territories being given names like “The island of five mountains discovered by the Dutch in 1616”, and the fact that map makers thought it important to label massive swathes of the ocean as “floating seagrass”. These types of details were one of my favorite parts of completing the project, for they are unique to every single map; some of the figures I studied did not have a lot of writing, while others had paragraphs upon paragraphs of Latin. Each one of the artifacts in the Greene Map Collection appears to be created on a different ideal and purpose – some are densely educational, with hydrographic and urban-planning information, while others appear to focus on a navigational purpose. Furthermore, while many maps appear to be sanctioned by scientists, geographers and experts, others have decidedly anecdotal information prominently displayed or mysterious descriptions of “unknown” lands. These observations inspired a significant part of my central line of inquiry; I wanted to investigate the progression of maps through time, as well as exploring the features that differentiate them.

I also plan on using the inscriptions on these maps to explore some of the pre-colonization history of the Caribbean, and to uncover language traditions hidden in cartography. In two maps produced just seven years apart, there are significant differences in which they portray the Caribbean Islands; one of them, a British production, appears to still retain traces of the indigenous language of populations that were decimated by European colonists. As discussed in my previous blog post, the names given by the Taino people to the lands they inhabited have riveting background histories – some honored Taino chiefs and warriors, others referred to their traditions and ways of life. I wanted to continue looking at this, to understand how the territories of the Caribbean sea would have been named if the Indigenous people who originally inhabited them had not been massacred and their culture erased.

A word of gratitude to Mr John Greene and Mrs Linda Greene: This opportunity has been an unique experience in my college life – to interact with an immeasurable collection of mint-condition maps spanning 600 years. I would have never been able to see and study any of these resources had it not been for their acquisition, collection and preservation of thousands of maps, as well as their generosity. Thank you for donating your collection to Johns Hopkins University and allowing students the opportunity to research with them.