Posts in this series were written by undergraduate students in the spring 2020 Museums & Society class Scribbling Women: Gender, Writing, and the Archive. We used rare books, archival materials, and digital primary sources in the Sheridan Libraries’ collections to prompt and guide inquiries into the creation, reception, preservation, and legacy of texts from the 1820s through the 1930s—speeches, private writings, and published poetry, fiction, and journalism—by North American women who brought attention to race-, gender-, and class-based inequities. Through their short essays, bibliographies, and analyses of digital sources, students are providing to a broad audience accurate information about and appreciation for the “scribbling women” they studied. For more about our series title, please see the first post. For more about our public-facing work, please see our gallery of final projects and blog.

Today’s post is by Riya Rana, Class of 2020, an International Studies, Sociology, and Economics major.

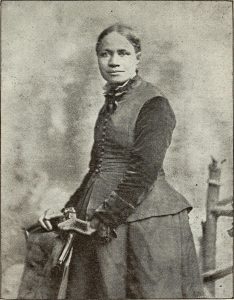

Photograph of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, from Women of Distinction: Remarkable in Works and Invincible in Character, by L. A. Scruggs (Raleigh NC: Scruggs, 1893). Image via Wikimedia.

In May 1866, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper addressed the Eleventh National Women’s Rights Convention in New York. At this convention, the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was founded, which initially advocated for suffrage for women and for African Americans—although it later broke apart on this very question. Harper’s speech, published in the convention’s Proceedings and accessible online through the Archives of Women’s Political Communication at Iowa State University, is fittingly titled “We Are All Bound Up Together.” In it, Harper urges unity between white women and black women in America. Identified as a “leading poet, lecturer, and civil right activist” by the Archives of Women’s Political Communication, Harper symbolized a unique bridge between the anti-slavery and suffrage movements despite threats to interracial solidarity in the post-bellum period. What does Harper’s speech, delivered to a gathering of white women suffragettes like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Lucretia Mott, reveal about the ways in which Harper navigates these tensions between race and gender?

Harper’s speech starts on a humble note as she proclaims herself to be a novice on the stage, although in fact she was already an experienced and renowned abolitionist lecturer (“Frances”). Her speech begins with an evocative anecdote about the bankruptcy proceedings she faced after her husband’s death; after a land administrator reclaimed her possessions, she was keen to demand women’s rights because “justice is not fulfilled so long as woman is unequal before the law” (Harper). Harper’s anecdote lays the foundation for her central argument: injustice against any individual is a failure of the country as a collective. She immediately applies this argument to the context of racial inequality, explaining that America’s attempts to suppress black folks hurt America itself by impairing the morality of poor white men, who were neglected by rich slaveholders and political elites. Harper’s transition from an anecdote of her gendered struggles as a grieving widow to her impassioned condemnation of racism and slavery in America is deliberately marked by her language; she begins with a sympathetic account that unifies humanity under the term “we” as she claims “we are all bound up together” in this country. The shift in her speech to the injustices facing black Americans is accompanied by her switch from the unifying “we” to the accusatory “you,” as she argues that her white audience is responsible for black oppression.

This movement from “we” to “you” highlights the tensions Harper faced as one of the few prominent black women in predominantly white organizational spaces filled with racism and nativism (Little). She confronts these contradictions through her central argument against injustice; her speech emphasizes the shared struggles at the root of both black Americans and the white working class, thereby linking their experiences as citizens who must possess and protect common rights. While the switch from “we” to “you” might seem incidental, it marks a crucial development in the speech, signalling a fundamental transition from the rhetoric of sisterhood to that of critical solidarity, from non-threatening humility to divisive candor, from gathering to intersectionality.

The rest of Harper’s speech analyzes these intersecting modes of race and gender while underscoring the importance of interracial suffrage and solidarity. She explicitly details the hypocrisies of white supremacy, such as America’s reliance on black men as soldiers who can die for the country but cannot receive full citizenship rights. These accounts of injustice are central to Harper’s argument that a wrong against an individual is a stain on the collective; she does not pretend that suffrage is a panacea for “all the ills of life” (Harper). Instead, Harper rejects mainstream, idealized notions of white womanhood by revealing the role of white women as perpetrators of racism and violence.

Harper’s eloquent navigation of spaces for both gender and racial equality reveals crucial dilemmas that we continue to experience today. As a black woman in predominantly white activist spaces such as suffragette conventions and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, Harper was part of organizations in which privileged white women often positioned themselves as liberators while they excluded and de-centered black voices from their agendas. Harper’s speech is a critical examination of these networks of privilege, and her words emphasize that activism is not simply a gathering of like-minded people. Rather, spaces of activism rely on and reproduce hierarchies of privilege, power, and priorities. Critical analysis of activist spaces can provoke internal divisions, which may bring readers to question why Harper risked backlash from both white suffragists (for criticizing their complicit racism) and black activists (for working among white colleagues). Harper’s goal is not to inspire depoliticized pity for black oppression from her audience of white women; rather, she insists that black and white people share a common humanity in order to engender active cooperation and solidarity that transcends prejudice and identity politics. Her central argument, which details how oppression inflicts a wound on both the oppressors and the oppressed, is essential to understanding why providing gender equality (women’s suffrage) without racial equality (black enfranchisement) is not a partial victory but rather a collective failure.

Works Consulted

“Frances Ellen Watkins Harper.” The Baltimore Sun, 7 Feb. 2007. www.baltimoresun.com/features/bal-blackhistory-harper-story.html.

Harper, Frances Ellen Watkins. “We Are All Bound Up Together.” Proceedings of the Eleventh National Women’s Rights Convention, Held at the Church of the Puritans, New York, May 10, 1866 (New York: Robert J. Johnston, 1866). Online at the Iowa State University Archives of Women’s Political Communication. https://awpc.cattcenter.iastate.edu/2017/03/21/we-are-all-bound-up-together-may-1866/.

Little, Becky. “How Early Suffragists Sold Out Black Women.” History Stories, A&E Television Networks, 8 Nov. 2017, www.history.com/news/central-park-to-get-its-first-ever-statues-of-real-life-women.