Going on a college campus tour is a bit like watching a live-action commercial; by the end, it is not hard to feel as though you are being offered a product with the capacity to significantly improve your life. Of course, some claims about the “product” arouse skepticism. Such was the case when I heard on a Hopkins campus tour that students here, even those in their first year, are provided ample opportunity to participate in research. And yet my suspicions have been proven wrong. In my freshman year at Hopkins, I have had the chance to pursue not one, but two research projects.

Going on a college campus tour is a bit like watching a live-action commercial; by the end, it is not hard to feel as though you are being offered a product with the capacity to significantly improve your life. Of course, some claims about the “product” arouse skepticism. Such was the case when I heard on a Hopkins campus tour that students here, even those in their first year, are provided ample opportunity to participate in research. And yet my suspicions have been proven wrong. In my freshman year at Hopkins, I have had the chance to pursue not one, but two research projects.

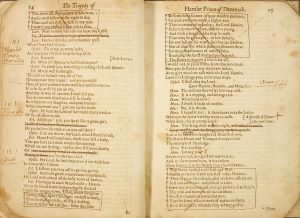

One of those projects has been my Freshman Fellowship in Special Collections. My research topic changed throughout this semester; in my last blog post, I wrote about comparing productions of Hamlet in West and East Germany. It became clear, however, that I would have more success pursuing a different course of study. I instead chose to research Hamlet through the lens of language, examining how revisions and annotations to the text tell us something about its accessibility and primary audience. My findings indicate that Shakespeare’s endurance as a cultural icon may in part be explained by the extent to which his work has been adapted to particular times in history. Extensive annotations and historical notes have been added to later editions of the play to make the language more accessible to the young scholar. Even in 1676, actors putting on the play were revising certain phrases to make them clearer for their audience. Charles and Mary Lamb, in their 1872 edition of Tales from Shakespeare for Young People, provide an interesting example of Shakespeare being used for a clearly-defined purpose: the cultivation of virtue.

It is easy to think of these discoveries in terms of how they impacted large groups of people, and there is value in such an approach. But I challenged myself throughout my research to think of individuals. I imagined the excitement of a young girl, previously denied access to her father’s library, reading Shakespeare for the first time. I reflected on the boldness of a 17th-cenutry actor choosing which portions of Hamlet to cross out. Of course, it is impossible to fully know and appreciate the reactions that various people have had to Shakespeare throughout time. But I do understand something of how people today view Shakespeare; in fact, I was given the chance to make my own observations when I presented my research at the Peabody Library on May 6th. I am grateful to have had that experience for so many reasons: the grandeur of the location itself, the excitement I felt at sharing my findings with an interested public, the chance to practice cogency in summarization. But I took the most joy in the conversations I had with attendees, from the mother who delightedly snapped a picture of the 1676 promptbook to send to her actor-in-training son to an older woman who recalled reading a later edition of Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare for Young People.

I noted in my application essay for the Freshman Fellowship program that “to read Shakespeare is to catch a glimpse of what it means to be human.” I stand by that observation, though it feels only right to expand it in light of the research I have done. Shakespeare is indeed a powerful conveyor of the human condition, but there is also significance in the ways that we ourselves interact with the text. The brilliance of Shakespeare’s works has not dimmed because people are constantly breathing new life into it: transforming its purpose, mining its text for hidden insights, bringing color and vibrancy to his stories with innovative adaptations. This reciprocal relationship between text and reader is what sustains Shakespeare’s relevance, and it’s a large part of what made this project so fascinating.

In closing, I offer my gratitude to all the wonderful people who facilitated this experience. It’s been a privilege and a pleasure to work with my mentor, Amy Kimball. All expectations I had at the beginning of this project have been exceeded, in large part because of her. I also extend my thanks to the other Freshman Fellows: Kiana Boroumand, Lucy Massey, and Faith Terry. They have taught me that research should be shared — not to feed self-importance or arrogance but because there is enormous value in collaborative effort and the creativity it often sparks. I was thoroughly inspired by the freshness of thought they brought to their respective topics, and I await with eagerness their next great discoveries.