Caroline West is an international studies major from Chattanooga, TN. She considers the Special Collections to be the perfect place to engage her various passions, which include history, politics, art, Shakespeare, and language.

Caroline West is an international studies major from Chattanooga, TN. She considers the Special Collections to be the perfect place to engage her various passions, which include history, politics, art, Shakespeare, and language.

Zora Neale Hurston, American novelist, once wrote that “nothing that God ever made is the same thing to more than one person.” A slight revision of this quote to read “nothing that Shakespeare ever wrote is the same thing to more than one person” aptly summarizes one of the most important lessons I have learned so far in my research in Special Collections. Of course, I didn’t embark on this project believing that there were only a few analyses of the works of Shakespeare. One visit to the library’s section of books on Shakespeare is sufficient evidence of the plethora of ways people have interpreted the great bard’s works throughout history. That is why I believe the revised Hurston quote to be so applicable. Every person that examines Shakespeare, with few exceptions, comes to his works with fresh eyes, and thus, the possibility of a completely unique interpretation.

Coming to such a conclusion is at once encouraging and daunting. It supports the idea that I might have something of value to add to the existing vast breadth of Shakespearean research. But I am also aware that Shakespeare’s works have been studied for centuries; it is difficult, if not impossible, to find an angle that has not already been explored. All that being said, I am hopeful that, at the end of the academic year, my research will have yielded knowledge that, if not completely new and unique, is at least interesting to the intellectual community at Hopkins and beyond.

The topic I intend to explore is a comparison of productions of Hamlet in West and East Germany in the mid-to-late 20th century. Those locations lend themselves particularly well to Hamlet for one pertinent reason: East Germany, at the height of its stability, was arguably the world’s most perfected surveillance state. The primary theme, among others, in Hamlet is surveillance. Thus, I believe there is fertile ground for comparisons between East Germany and Elsinore, which would have introduced conflict between the East German government and theater directors. Indeed, I was inspired to choose this particular topic after reading an article in the New York Times about a production of Hamlet in East Germany that was shut down after the government suspected a political statement was being made through emphasizing the line “Denmark’s a prison.” I’m particularly interested to discover how cultural differences between West and East Germany, many of which are still evident today, were reflected in Hamlet productions.

I consider my research worth conducting because it engages many of my passions: the intersection of art, culture, and politics, German history, Shakespeare, language…the list goes on. Furthermore, I am eager to investigate each of these subjects for myself, to rely not simply on what I read in a textbook, but to form conclusions based on my own understanding of documents from past eras. But I understand that others might need more convincing. What is the value of studying old documents and books? The frequent advances we’ve made in technology in the past few decades have practically hardwired us to be forward thinking. We’re captivated by the possibilities of the future; the realities of the past, both beautiful and broken, are less comfortable to contemplate. We reach for the e-reader, not the yellowed manuscript from bygone centuries.

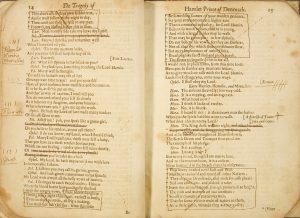

It is in Special Collections, I believe, that we see a more perfect marriage of the past with the present. Through Special Collections, a document or a book from 1616 is preserved with the technology of 2016. It is the fusion of the two that broadens our understanding of our world and our history, recognizing that one is not necessarily superior to the other. It’s not easy to find that balance between appreciating the past and believing wholeheartedly in the potential of technology and progress to create a better future.

Germany is particularly fertile ground for examining how exactly we achieve that balance, because Germany’s history is a blend of the most brilliant of lights with the darkest of evils. Its government perpetrated the worst genocide in human history, and it is also the homeland of masterful artists, scientists, musicians, and intellectuals. So how does one create an image of Germany that recognizes these blatant contrasts without giving greater value to either end of the spectrum? There’s a word in German that I think serve this purpose: Vergangenheitsbewältigung. To my knowledge, this word has no exact English equivalent; its approximation is “grappling with the past.” This is the starting point for understanding why Germans, as a German friend of mine once put it, “are proud of not being proud.”

This is also how one unravels the multitude of threads in Germany’s history, a past that includes darkness sometimes so evil and brutal that it seems nearly impossible to overcome. But there is light in this country’s appreciation for Shakespeare, in the brilliance of playwrights like Bertolt Brecht, in the art and music its citizens have produced, in the fierce compassion of Angela Merkel’s response to the refugee crisis, in the way that it has doggedly knit itself back together, undeterred by knots and tangles along the way. Inherent in my research is this idea of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, and in my opinion, that’s reason enough to spend time in Special Collections. I seek to fashion a vision of the past that is neither too rosy nor too bleak, that appreciates how far we have come and how far we still have to go. That seems particularly critical, perhaps now more than ever before. I don’t expect through my findings to create such a foundation for all future research, but perhaps I can at least lay a few stones.