Recently I had to give up my personal Facebook archive. It’s a long and boring story, but something I never expected to be asked to do and it felt wrong…maybe a tiny bit icky. It got me thinking more about privacy and the places we store information online. While you might not realize it, librarians tend to think about privacy a lot and even have a Library Bill of Rights. What you might not know, is that since the Patriot Act was enacted and expanded, there have been librarians under gag orders who could not publicly speak out about their experiences related to the FBI demanding that patron data be handed over.

In July 2005, two FBI agents visited the Library Connection in Connecticut. The Library Connection is non-profit cooperative of library databases that arranges record-sharing between 27 different libraries and tracks book rental and other services. The agents handed The Library Connection’s executive director a document that demanded that he produce any and all “subscriber information, billing information and access logs of any person or entity” that had used library computers for 45 minutes on February 15, 2005 in any of the 27 libraries whose computer systems were managed by the Library Connection. The FBI wanted the private data on library patrons to protect against international terrorism.

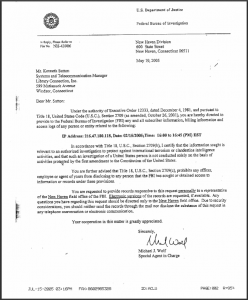

A National Security Letter (NSL) is a written directive to produce records that the FBI issues to third parties, such as telephone companies, Internet Service Providers, banks, consumer credit reporting agencies, and libraries. The legal framework for NSLs was established by Section 505 of the USA Patriot Act in 2001. Recipients of an NSL are typically under a perpetual gag order and are not permitted to disclose it. A library can be required to hand over books, documents, computer files, and hard drives for an investigation to protect against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities. Such letters existed before the Patriot Act, but were greatly expanded by the law.

If you worked for the library and received one of these letters, you could not speak of it ever. Librarians protested the renewal of the Patriot Act, but lost in a tie. What would library staff do if they couldn’t talk about it? Ever? They started to get creative and post canary signs, which read something like “The FBI has not been here today, but watch closely for this sign to be removed.” The Connecticut librarian was under a perpetual gag order, unable to speak out or testify about it during a debate over the Patriot Acts’ renewal. Eventually the gag order was lifted and a group of librarians, known as the Connecticut Four in library circles, began to speak out publicly.

Many libraries gather the minimum amount of patron information needed for library operations, and if you’re curious, you can see exactly what type of data is collected by the JHU Libraries. The American Library Association recommends that if a library collects data about patrons for planning, library staff should do so in a way that protects the identity of the patron. As long as records exist, however, librarians cannot ensure confidentiality, because agencies will seek this information and can do so more easily under the Patriot Act. If a library or library vendor is going to store patron data then the librarian should ask for the patron’s permission and tell them about the risks.

Many librarians feel privacy is a basic right and strongly support a First Amendment right to receive information from a publicly funded library. Courts have upheld privacy rights based on the Bill of Rights of the U.S. Constitution. Ultimately, however, the biggest threat to privacy is not an NSL, but it is you. It’s me. It’s the choices we make in how much information we self-publish through Facebook, Twitter, or give away to third party services who may store data far longer than a library. It’s the privacy rights we give over to vendors and other companies in exchange for services we like, such as recommending related books or personalizing our accounts to our liking. How many times have you quickly scrolled or clicked through service agreements without really reading them deeply? I know I have in the past, but from now on, I plan to think more intentionally about my online presence.

I thought I had nothing to hide in that Facebook archive, and actually, I didn’t…but it didn’t make it feel any better to hand it over and worse still that others were sifting through and reading it. Once I realized what it felt like to turn over that personal data myself, on a much smaller and humbler scale than an NSL, it was too late to stop others from seeing it. For our much larger online footprint, we owe it to ourselves to think about what we are putting out there about ourselves, how we feel about it overall, and start to think about it.