By Rob Gamble, Processing Assistant and Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History

Part of a monthly series of posts highlighting uncovered items of note, and the archival process brought to bear on these items, as we preserve, arrange, and describe the Roland Park Company Archives.

Historians are trained to think critically about the archives they use, both at the micro- and macro- level. We must be attentive to the context and motivations behind the production of individual artifacts or documents (see my previous blog post!). This requires asking broader questions about how and why these historical materials were preserved and collected in the first place.

This much I knew, at least in an abstract sense. What I failed to grasp before beginning work on the Roland Park Company Archives last fall was the extent to which archivists have a role not only in making possible but also in shaping our knowledge of the past. Processing the Roland Park records has given this historian-in-training a deeper appreciation for the artistry and patience of the archivist.

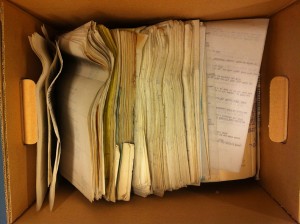

As the “before and after” pictures accompanying this blog post illustrate, few archival collections come ready-made.

When Johns Hopkins University acquired the Roland Park Company Archives from its previous holder, Cornell University, it obtained more than just cardboard boxes with papers in them. It also took possession of the systems of organizing and classifying documents applied by the collection’s previous holders, Cornell and the Roland Park Company. Like their predecessors at Cornell, archivists at Johns Hopkins remain dependent upon, and limited by, how the company originally categorized and physically housed its records. Shortcuts in filing procedures taken eighty years ago were permanently inscribed in the archive.

A prime illustration of how archives are produced over time can be seen in Cornell’s finding aid to the collection. Written in 1984, the document provides the only comprehensive description of the enormous collection and has been indispensable in helping to process the collection at Johns Hopkins. For a number of reasons, however, it requires updating. It was not as simple as slapping Johns Hopkins labels over Cornell labels.

The main reason stems from the need to better protect and preserve these documents. As the company wound down its operations in the late 1950s and early 1960s, its file cabinets were boxed up and would eventually land at Cornell in 1968. In the process of moving the files, however, some cabinets were more carefully transferred than others. This is reflected in the widely varying orderliness and cleanliness of the 300-plus boxes in the collection. Cleaning, flattening, and placing the loose papers into acid-free folders not only makes them easier to access but also better ensures their longevity—not to mention saves patrons from coming across any organic matter left by animal interlopers! Cornell had initiated this process, but much more work was needed.

Placing loose papers into folders brought to light other issues, most notably the inefficient use of space. Some boxes were bursting with papers, others only half full. With limited shelf real estate in Special Collections, reducing the number of boxes makes the lives of both archivists and patrons easier.

Archivists constantly are faced with the challenge of balancing the intentions of the original authors, or what we can gather of them, with the needs of researchers and realities of processing. As a historian, I am tempted to speculate on just what the increasing disorder of the collection by the 1940s and 1950s says about the Roland Park Company and its evolution. Working the Archives, however, I recognize that there are too many factors that could serve to explain the collection’s varying degrees of organization and disorganization. In other words, the Roland Park Company was not the only “author” of its archival collection—so too were the movers it hired, the archivists who have stewarded these records over time, and even the research patrons who have used and cited the collection.