If you’ve read anything by Stephen Crane, there’s a pretty good chance it was The Red Badge of Courage. Crane’s Civil War story is renowned for its insider perspective on combat experience—what it was like to be surrounded by gunsmoke, explosions of light and sound, bullets, wounded men.

The Red Badge of Courage raises two questions. First, with its straightforward presentation of its protagonist’s initial cowardice and eventual valor, is it a critique of war, an exaltation of battleground bravery, or simply a realistic portrayal of soldierly transformation? And secondly, how did Crane do it? Written thirty years after the war’s end by an author who had never seen military action, The Red Badge of Courage managed to create such a convincing sense of warfare that Civil War veterans claimed to have served with Crane.

The first question may be unanswerable. The second invites a bit of detective work. And that’s exactly what some undergraduates did this semester in our class “American Literature on Display.” After reading Crane’s novel, we examined some of the books and magazines of the late nineteenth century that Crane could have used to help him imagine the Civil War battlefields he so compellingly evoked. Students then described their research on our class blog.

We know that Crane read a series of articles about the Civil War in The Century Magazine. The many biographies, memoirs, criticisms and documents published in the “Civil War series” constituted a major national debate, and were eventually collected into a four-volume book. But what exactly did Crane glean from The Century? And what else might he have encountered in American print culture to shape his view of war? As it turns out, publications about the Civil War were voluminous at century’s end; Crane would have had access to a lot of material.

The Century often portrayed “war as a glorious entertainment, rather than a bloody conflict,” according to Katie Naymon. For example, “… the picture that… accompanies an article about the Battle of Bull Run… isn’t completely realistic… the focal point of the picture is a man on a horse, flag-waving, hand raised in victory.”

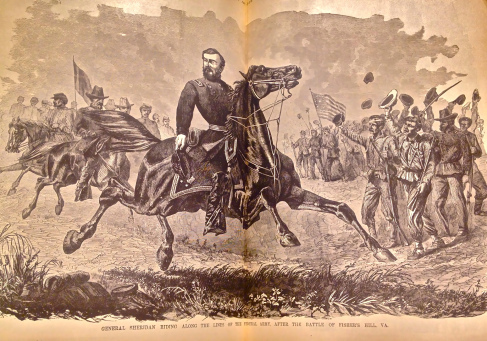

This chivalric figure of victory seems to have been prevalent in the 1880s; Zoe Ovans discovers another work that also calls up “the image of a magnificent general, astride a gallant horse, posed and ready to outwit the enemy and defend his comrades… The Soldier in Our Civil War, a pictorial history of the American Civil War… focuses on the valor of the soldier in the field of battle… [One] image stands out among the rest: in the section describing the battle of Fischer’s Hill, there is a marvelous two-page spread featuring General Sheridan ‘riding along the lines of the Federal army.’”

Alyssa Zelicof notes, however, that while this volume “hones in on the gallantry and boldness of soldiers such as ‘Colonel Ash, Charging into J.E.B Stuart’s Camp, Near Charlottesville, V.A.’,” Crane’s narrative asks us to question that stereotype: “The sincere depiction of war given by Crane gives insight into the psyche of a soldier in battle, and forces one to question the thought process of soldiers such as Colonel Ash. As he charges gallantly into the camp, is he thinking about his children and wife at home? Although his face reads as unsympathetic, could he be silently praying to make it out of battle alive? Henry’s observations humanize the stoic actions of a soldier, and highlight the false depiction of bravery in war.”

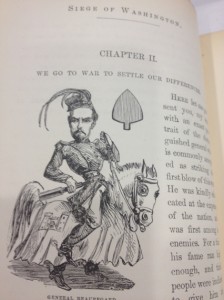

The valor on display in the 1880s was not without precedent, as we learned when looking at materials published during or soon after the war. In fact, it can appear in some shocking places. Rachel Witkin finds a caricature of the heroic horseman in The Siege of Washington D.C.: Written Expressly For Little People, a strangely light-hearted history of 1867 that might help to explain why war often finds so many eager participants: “Children would most likely laugh at how ridiculous the general looks on his horse and think that war is nothing but a game, or think that the general looks important and want to enlist in war. The chapter name is even more chilling, as it suggests that war is a normal way to settle one’s differences. These children will glorify war, like Crane’s ‘youth’ did, and have no idea what’s actually in store for them.”

The valor on display in the 1880s was not without precedent, as we learned when looking at materials published during or soon after the war. In fact, it can appear in some shocking places. Rachel Witkin finds a caricature of the heroic horseman in The Siege of Washington D.C.: Written Expressly For Little People, a strangely light-hearted history of 1867 that might help to explain why war often finds so many eager participants: “Children would most likely laugh at how ridiculous the general looks on his horse and think that war is nothing but a game, or think that the general looks important and want to enlist in war. The chapter name is even more chilling, as it suggests that war is a normal way to settle one’s differences. These children will glorify war, like Crane’s ‘youth’ did, and have no idea what’s actually in store for them.”

Civil War-era books not only romanticized war for children, but also romanticized the child who is already at war, as Tiffany Kim observes in A Selection of War Lyrics. The poem “The Color-Sergeant,” she explains, “is about a flag boy, Walter, who dies in battle. Moreover, it is about celebrating his death. A flag gives strong visual representation to otherwise intangible pride and morale. Therefore, the flag boy is extremely important to the idea of war, the idea being to protect what the flag represents. In the poem, Walter is honored for being a brave man and being ‘in the thick of the fight’ (line 14) to carry ‘the flag of the Free’ (line 4). Although he is not the big man on the battle field, he is seen as an important figure and a hero.”

Civil War-era books not only romanticized war for children, but also romanticized the child who is already at war, as Tiffany Kim observes in A Selection of War Lyrics. The poem “The Color-Sergeant,” she explains, “is about a flag boy, Walter, who dies in battle. Moreover, it is about celebrating his death. A flag gives strong visual representation to otherwise intangible pride and morale. Therefore, the flag boy is extremely important to the idea of war, the idea being to protect what the flag represents. In the poem, Walter is honored for being a brave man and being ‘in the thick of the fight’ (line 14) to carry ‘the flag of the Free’ (line 4). Although he is not the big man on the battle field, he is seen as an important figure and a hero.”

Of course, for most Americans living through the Civil War, newspapers and magazines were important sources of information about wins, losses, casualties, advances. The Confederate press suffered from shortages of supplies and labor; many of the books published in the South in this period are poor in quality. The press of the North, without those constraints, was developing novel ways of delivering the news. Notable in this respect was Harper’s Weekly, with its many newsy illustrations. Since photographs could not be reproduced upon the printing press at this time—and since the paraphernalia of collodion process photography was too cumbersome, slow and fragile for action shots anyway—war-time images were conveyed through wood-engravings by artists like Thomas Nast and Winslow Homer.

These images served multiple purposes. Certainly, as Rosa Acheson notes, there were depictions of heroes. The cover of the issue for May 3, 1862, for example, contains eleven portraits of military leaders, each one framed like a keepsake. But these portraits seem more informational than epic. “Each portrait is a close up, showing just the torso and face, so we are really able to distinguish what each man looks like. Some of them have glasses, others mustaches. All of them, despite their war uniforms, look like regular men. Of course the public recognition of these men as Civil War heroes was earned. However, the intention here is instead to put a face to the brave actions, to characterize individuals who we otherwise might just consider a small part of the larger story.” Similarly, in a Harper’s picture called “The Captured Flag,” Bianca Kenworthy sees both the familiar image of bravery and an impulse towards factual accuracy that is in line with Crane’s story—and even surpasses it: “the trees and hill of the image’s landscape match those described in passages found in Crane’s novel; Crane’s emphasis on the confusion-laden regiments can be seen in the image by the clusters of people as well as those who are struggling and have fallen or been killed. However, as many similarities as there are, certain key and subtle differences between the picture and Crane’s prose should be noted. For example, Crane divorced his novel from any precise historical context by omitting dates and named locations whereas this image can be dated and placed, lending it a heightened sense of visual credibility.”

The tension inherent in war-time reporting, between baring the pain of sacrifices made and honoring and perhaps mythologizing those sacrifices, comes across even in personal narratives of the time, as Alex Hamm notes in his reading of The Boys in Blue, with its long nineteenth-century subtitle, Heroes of the “Rank and File.” Comprising Incidents and Reminiscences from Camp, Battle-Field, and Hospital, with Narratives of the Sacrifice, Suffering, and Triumphs of the Soldiers of the Republic. “In sharp contrast to the realism of Crane’s work of retrospective fiction, when we look at the visual representations that come from contemporary histories of the war, we see lots of order and decoration… this may have been a sort of propaganda by the illustrators of the 1860s in an effort to inspire the people after the Union victory… we can see the difference between what the people of the era wanted to believe and what they knew really was true.”

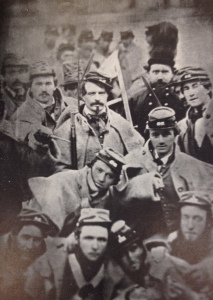

Several decades after the Civil War—around the time that Crane wrote The Red Badge of Courage—half-tone technology was invented, allowing for the publication of photographs, and soon the war received another series of illustrated treatments. Do actual photographs of the war tell a more accurate story, without the temptations of heroic tales? Was Crane’s work a response, perhaps, to some new, more factual aesthetic? Well, if The Photographic History of the Civil War is any indication, maybe not. As Marah Formanek points out, this ten-volume series was published on the semi-centennial of the war, “as a token of remembrance and an explanation of the soldiers and the battles that occurred between 1861 and 1865. The photograph below depicts a scene of the Confederate soldiers, or the ‘Boys in Gray,’ before their first battle at Bull Run. They are young, jovial, and confident before their first encounter with the true tragedies of war. The photograph is captioned with the comment that, ‘there is not a serious face in the picture.’” Perhaps. But however you read the image, what is clear is that the commentators in 1911 were still expressing a kind of optimism that Crane, in contrast, was intent on challenging.

Several decades after the Civil War—around the time that Crane wrote The Red Badge of Courage—half-tone technology was invented, allowing for the publication of photographs, and soon the war received another series of illustrated treatments. Do actual photographs of the war tell a more accurate story, without the temptations of heroic tales? Was Crane’s work a response, perhaps, to some new, more factual aesthetic? Well, if The Photographic History of the Civil War is any indication, maybe not. As Marah Formanek points out, this ten-volume series was published on the semi-centennial of the war, “as a token of remembrance and an explanation of the soldiers and the battles that occurred between 1861 and 1865. The photograph below depicts a scene of the Confederate soldiers, or the ‘Boys in Gray,’ before their first battle at Bull Run. They are young, jovial, and confident before their first encounter with the true tragedies of war. The photograph is captioned with the comment that, ‘there is not a serious face in the picture.’” Perhaps. But however you read the image, what is clear is that the commentators in 1911 were still expressing a kind of optimism that Crane, in contrast, was intent on challenging.

Watch this space for more from these students! They’ll be creating a digital exhibition to complement and extend “For Love or Money: Art, Commerce & Stephen Crane.”