The following blog post was written by David Farris of The Sheridan Libraries Reserves Department. While a graduate student at the Peabody Institute, David worked as a student employee at the Peabody Library. There, he spearheaded a project to identify and inventory all of the titles included in the gift by John Pendleton Kennedy.

John Pendleton Kennedy (1795-1870) was a leading figure in Baltimore society during the mid-Nineteenth Century. A veteran of the War of 1812, he trained and worked as an attorney and was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates and the U.S. Congress; however, Kennedy’s true passion was writing.

John Pendleton Kennedy (1795-1870) was a leading figure in Baltimore society during the mid-Nineteenth Century. A veteran of the War of 1812, he trained and worked as an attorney and was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates and the U.S. Congress; however, Kennedy’s true passion was writing.

In 1819, Kennedy began his first foray into the literary world in collaboration with Peter Hoffman Cruse on the periodical The Red Book, “a satiric potpourri in the Spectator tradition” (Bohner, 36). In addition to the periodical, Kennedy wrote three novels: Swallow Barn; or, a Sojourn in the Old Dominion (1832), Horse-Shoe Robinson, a Tale of the Tory Ascendency (1835), and Rob of the Bowl, a Legend of St. Inigoes (1838); the anti-Jacksonian satire Quodlibet (1840), Memoirs of the Life of William Wirt (1849) and published several speeches and papers.

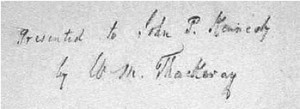

He counted among his friends and personal acquaintances George Henry Calvert, James Fenimore Cooper, Charles Dickens, Washington Irving, Edgar Allan Poe, William Gilmore Simms, and William M. Thackeray. In his journal entries from September 1858, Kennedy wrote that Thackeray asked him for assistance with a chapter in The Virginians: Kennedy provided Thackeray with scenic descriptions of the Virginia landscape (Bohner, 219). However, there is a disputed account, perpetrated by John H. B. Latrobe in his article for Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography, in which Kennedy is said to have written the fourth chapter of the second volume of The Virginians (Gwathmey, 131-33).

Additionally, Kennedy was an early champion and later patron of Edgar Allan Poe, whom he met after Poe won a writing contest, of which Kennedy was a judge, sponsored by the periodical, Saturday Visitor (Ridgely, 66).  John Pendleton Kennedy was one of the men chosen by George Peabody, whom he befriended when they served together in the War of 1812, to organize the creation of the Peabody Institute (est. 1857), a gift from Peabody to the city of Baltimore (Parker, 88-89). Having served with distinction on the Board of Trustees and then as the second president of the Peabody Institute for a decade, John Pendleton Kennedy’s professional and personal association with George Peabody and the Institute led to his decision to bequeath his personal library and manuscripts to the Peabody Institute. In his Last Will and Testament, Kennedy writes:

John Pendleton Kennedy was one of the men chosen by George Peabody, whom he befriended when they served together in the War of 1812, to organize the creation of the Peabody Institute (est. 1857), a gift from Peabody to the city of Baltimore (Parker, 88-89). Having served with distinction on the Board of Trustees and then as the second president of the Peabody Institute for a decade, John Pendleton Kennedy’s professional and personal association with George Peabody and the Institute led to his decision to bequeath his personal library and manuscripts to the Peabody Institute. In his Last Will and Testament, Kennedy writes:

I give to the Peabody Institute…my library, comprising all my books, pamphlets, maps and charts…and this I give as a special donation from me for the use of the Institute, but not to be kept as a circulating library, by which I mean, not to be taken out of the library rooms of the Institute for ordinary use. I also give to the Institute my several bound volumes of the manuscripts of my printed works, which I have preserved in the original MS. copies, as also my two bound volumes of autograph letters which have been written to me. These I give to the Institute with a special request that they be carefully preserved as a testimony of my interest in its success. (Tuckerman, 485).

JPK: His Legacy and His Influence on the George Peabody Library

Long overshadowed by the recognition and reputation afforded to George Peabody for his generous endowment to the city of Baltimore, John Pendleton Kennedy’s vision and dedication to the founding and initial governing of the Peabody Institute is remarkable. As early as 1841, Kennedy was an advocate for improving the city of Baltimore by establishing “a Free Public Library, a Museum and School of Art and provisions in the way of Lectures” (Tuckerman, 390). In one of Kennedy’s last reports as President of the Peabody Institute, he wrote:

Our country is yet far from being gifted with a Library completely supplied to meet these requisites and fully to satisfy the research of students in their pursuit of that kind of knowledge which, being of rare demand, does not ordinarily find a place in private collections. And although this impediment to accurate research is gradually lessening before the awakened enterprise of the present time, still, it is our part, as I am sure it was Mr. Peabody’s wish we should so regard it, to use the munificent donation with which we are entrusted in the careful, persistent and intelligent application of our means to the gradual accumulation of everything notable in literature and science as necessary to the pursuits of the scholar. (Tuckerman, 399).

It is this same foresight, wisdom, and his numerous contributions which guarantee John Pendleton Kennedy a prominent and permanent place in the history of the Peabody Institute and the George Peabody Library.

Ray – The collection is still mostly intact. There were 1800 titles in the original gift and only about 115 are either missing or unable to be identified as having come from Kennedy. That’s not a bad percentage given the institutional changes that occured over the history of the Peabody Library.

Thanks Amy and David-interesing tidbit. Do you know how many books remained in the original donation of Kennedy? Was this a collection that remained fairly intact?

Ray