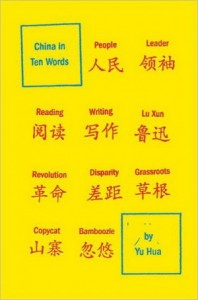

How is it possible to summarize a country as complex as China in ten words? Yu Hua, a renowned novelist in China, did just that. In his first work of nonfiction published in English, entitled China in Ten Words, Yu chose People, Leader, Reading, Writing, Lu Xun (a famous 20th century writer), Revolution, Disparity, Grassroots, Copycat, and Bamboozle to describe the past four decades of Chinese history, using each word as the prompt for personal memoir, social reportage, and political commentary.

How is it possible to summarize a country as complex as China in ten words? Yu Hua, a renowned novelist in China, did just that. In his first work of nonfiction published in English, entitled China in Ten Words, Yu chose People, Leader, Reading, Writing, Lu Xun (a famous 20th century writer), Revolution, Disparity, Grassroots, Copycat, and Bamboozle to describe the past four decades of Chinese history, using each word as the prompt for personal memoir, social reportage, and political commentary.

Formerly a small town dentist, Yu Hua burst onto the Chinese literary scene in the 1980s with a series of stories that were both stylistically innovative and thematically provocative. Having grown up during the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), Yu Hua found himself almost obsessively preoccupied with the twin specters of Chinese history: the revolutionary past and the human capacity for cruelty and violence. These became the central theme throughout his early works. For example, a story published in 1987, entitled “1986” (yi jiu ba liu nian), tells how ten years after the Cultural Revolution, people already forgot about the horrendous past: “The disastrous years of the Cultural Revolution have faded into the mist of time. The political slogans pasted again and again on the walls have all been painted over, obscured from the view of pedestrians strolling through the spring night, invisible to those for whom only the present can be seen” (The Past and the Punishments, 171). This collective amnesia, however, is disrupted by violent return of the past, in the form of a mad man, a former political prisoner who had lost his mind during the Cultural Revolution. In front of a shocked audience of townspeople, the mad man methodically dismembers himself, thus re-enacting and recalling the unspeakable horror of the past.

More than twenty years after he published “1986”, Yu Hua seems to still be wrestling with the idea of the haunting presence of the past in the present, the inescapable nightmare of history. On the surface, China today, with its single minded pursuit of economic growth, seems a far cry from its Cultural Revolution years. Yet, behind the gargantuan transformation China has gone through in the past few decades is a similar, if not the same, revolutionary fervor that had fueled the frenzy of the Cultural Revolution. To illustrate this point, Yu Hua gives ample examples, one of which is the forcible eviction of homeowners from their own homes. In the name of economic development, government backed developers resort to violence to force people out of their homes to make way for new highways or skyscrapers. Retelling one horror story of forcible home demolition after another, Yu Hua reminds the reader of the famous definition of “revolution” given by Mao Zedong, China’s supreme leader during the Cultural Revolution, “A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained, and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence.” China’s economical miracle, Yu Hua believes, relies “to a significant extent” on such violence (China in Ten Words, 127). Sure, such an economic model is efficient (“The government did not even give us time to surrender,” said one of the victims of forced demolition), but it is brutal.

The JHU library collection includes English editions of three of Yu Hua’s works, China in Ten Words (2011), Brothers (2009), The Past and the Punishments (1996). The library also has over 100 books dealing with the subject of the Chinese Cultural Revolution and over 1,000 titles on China’s modern and contemporary history.