A funny thing happened on the way to the twentieth century. Literary conventions, along with the artistic conventions native to most forms, came under attack. Anti-convention campaigns across the globe were given various names by the revolutionaries of various stripes who launched them: “impressionism,” “expressionism,” “symbolism,” “futurism,” “imagism,” “Dadaism,” “surrealism,” “lettrism”… but the term that generally applies to all of them is “avant-garde,” as in the “advance guard” of a new cultural order. (Or, to be fair, multiple new cultural orders…)

A funny thing happened on the way to the twentieth century. Literary conventions, along with the artistic conventions native to most forms, came under attack. Anti-convention campaigns across the globe were given various names by the revolutionaries of various stripes who launched them: “impressionism,” “expressionism,” “symbolism,” “futurism,” “imagism,” “Dadaism,” “surrealism,” “lettrism”… but the term that generally applies to all of them is “avant-garde,” as in the “advance guard” of a new cultural order. (Or, to be fair, multiple new cultural orders…)

One figure central to several of the avant-garde movements—at least geographically, as the doyenne of the Paris salons—was Gertrude Stein. Complementing our substantial holdings of avant-garde periodicals, books and ephemera, the Sheridan Libraries has a significant collection of works by Miss Stein: first or early editions of almost everything she published. Some of my students recently examined a few of these pieces and posted their interesting discoveries on our class blog.

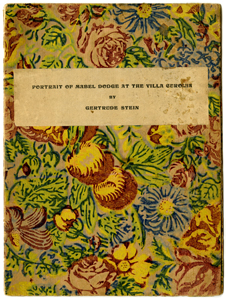

Natalie Moreno looks at Stein’s pamphlet Portrait of Mabel Dodge at the Villa Curonia (1912) and notes that its wallpaper binding is a sign of its status as a privately printed book—and thus of Stein’s long struggle with the publishing world. The poem inside, a portrait of Stein’s supporter Mabel Dodge Luhan, is also indicative of the importance of friendship and patronage in the avant-garde economy.

Natalie Moreno looks at Stein’s pamphlet Portrait of Mabel Dodge at the Villa Curonia (1912) and notes that its wallpaper binding is a sign of its status as a privately printed book—and thus of Stein’s long struggle with the publishing world. The poem inside, a portrait of Stein’s supporter Mabel Dodge Luhan, is also indicative of the importance of friendship and patronage in the avant-garde economy.

Anne Badman explores Stein’s career and friendships a few decades on down the line, via Before the Flowers of Friendship Faded Friendship Faded (1931). Here the relationship to the friend, poet Georges Hugnet, is antagonistic, reflecting an argument about Stein’s billing on the title page of Hugnet’s book of poems Enfances, which Stein was translating—or rewriting, depending on how you look at it. Before the Flowers was brought out by Stein’s own imprint, the Plain Edition, which functioned as a small press exclusively for Stein’s work… another technique Stein used to publish her experimental and oft-mocked work.

You can see these two delicate booklets for yourself in Special Collections, along with our other delectable Stein treats. Many of these works were donated by Robert Wilson, the former proprietor of the late, great Greenwich Village bookshop The Phoenix, or by the Broadway producer Mary Ellyn Devery, who assembled her collection with Wilson’s assistance. The Phoenix was a place where avant-garde works of literature could be bought and sold long before they met with mainstream approval, and was therefore central to their survival. Wilson’s legacy is appreciated in a memorial chapbook investigated by Emily Markert.

Stein seems to be enjoying something of a renaissance these days; her life, writing, family, art collecting habits and role in the twentieth-century avant-garde are the subjects of not one but two recent museum exhibitions. And perhaps you saw last year’s Woody Allen film Midnight in Paris, in which Stein was strangely impersonated by Kathy Bates. She’s also the ongoing subject of political controversy, due to her ties to French Nazis during the Second World War. Just how did she and Alice B. Toklas, the woman she called her wife—two prominent expatriate Jewish lesbians—get through the war years in France?

Stein seems to be enjoying something of a renaissance these days; her life, writing, family, art collecting habits and role in the twentieth-century avant-garde are the subjects of not one but two recent museum exhibitions. And perhaps you saw last year’s Woody Allen film Midnight in Paris, in which Stein was strangely impersonated by Kathy Bates. She’s also the ongoing subject of political controversy, due to her ties to French Nazis during the Second World War. Just how did she and Alice B. Toklas, the woman she called her wife—two prominent expatriate Jewish lesbians—get through the war years in France?

Stein’s notoriety is not exactly a new thing, however. Yes, she was central to the avant-garde movements of her own time, but she has continued to serve as a touchstone for the avant-garde in the mid-twentieth century and beyond. You can see her influence in the work of contemporary poets as different as John Ashbery and Lyn Hejinian.

And you can see it in the work of poet Robert Grenier, whose book Sentences (1978) was also the subject of a student’s inquiries. We use the term “book” here very loosely, as the work in question is a box of 500 index cards, each bearing a line of… something we could call poetry. Do you read the cards in order? Do the 500 sentences make one long poem, or 500 short ones? As Joella Allen notes in her blog post, Grenier’s work expresses the avant-garde’s DIY spirit and tongue-in-cheek resistance to convention: when asked if there was a relation between the 500 cards, Grenier replied, “None. But you can make one.”

And please do not over look Gertrude Stein’s To Do: A Book of Alphabets and Birthdays which is not a kid’s book but a cross between medieval primer and futuristic sudden fictions.