Langston Hughes was born on February 1, 1902—110 years ago today. It’s only a coincidence that his birthday inaugurates Black History Month, but to me the timing has always seemed like a fateful homage to the man whose work as a poet, story-teller and political activist laid the foundations for so many aspects of contemporary African American culture.

Langston Hughes was born on February 1, 1902—110 years ago today. It’s only a coincidence that his birthday inaugurates Black History Month, but to me the timing has always seemed like a fateful homage to the man whose work as a poet, story-teller and political activist laid the foundations for so many aspects of contemporary African American culture.

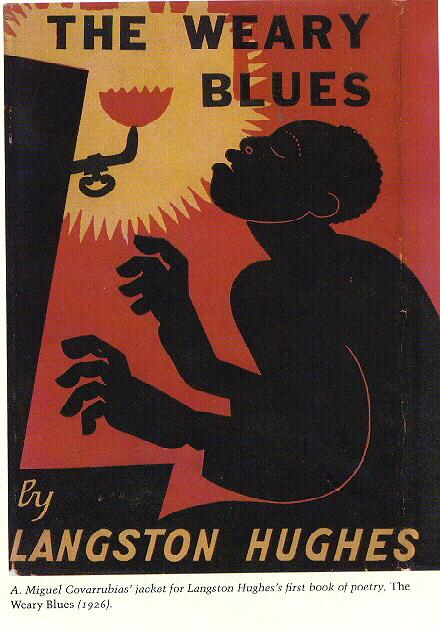

Hughes was a prodigy and a Renaissance Man in an era when those terms were not frequently applied to people of color. He entered the literary world with a bang in 1921, at the age of 19, when his poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” was published in the anti-racist periodical The Crisis, then edited by W. E. B. DuBois. When his first book of poetry, The Weary Blues, was published in 1926, the poem was dedicated to DuBois. It was not the first time that Hughes was associated with prominent men: in 1925 he worked for Carter G. Woodson, the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History and the “father” of African American history (it was Woodson, in fact, who started Black History Month); later that year, while working as a busboy, he was “discovered” by the poet Vachel Lindsay. (And now you know how the Washington, D.C. eatery and bookstore Busboys and Poets gets its name.)

Despite these mentors, Hughes was more often the subject of critique than appreciation in the 1920s and ’30s. In fact, he sought to distance himself from the middle-class aspirations of “Talented Tenth” redeemers like DuBois. In his manifesto “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” published in The Nation in 1926, he declared that a lot of what counted as culture for his African American peers reflected deep down a desire to “act white.” His own artistic aim, in contrast, was to celebrate “the low-down folks, the so-called common element, and they are the majority—may the Lord be praised!” So in his poems in The Weary Blues and later collections like Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927), Hughes uses dialect, depicts boisterous Harlem scenes and lets his characters hang loose. He was raked over the coals by Black critics for “holding up our imperfections to public gaze.”

Hughes got famous as a poet, but he also wrote novels, memoirs, plays, books for children and non-fiction works like A Pictorial History of the Negro in America (1956), a popular and accessible history equally suitable for the library or the coffee table. Accessibility was also a distinguishing characteristic of his beloved “Simple” stories from the 1940s and ’50s, which starred Jesse B. Semple as a kind of Harlem Everyman—a wise-fool witness to America’s changing social morés.

Hughes wasn’t content to be “just” a writer, however; he used his celebrity-hood as a platform for the exploration of vexing political issues. Hughes was a Communist sympathizer in the 1930s, a correspondent for the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper during the Spanish Civil War, an ardent Pan-Africanist and civil rights activist. Post-humously, he has been seen not only as a civil rights hero and artist who opened up new avenues of African American expression, but also as a possible gay icon. Hughes’ sexuality continues to be debated by biographers. It would have been difficult for him to be either “out” or “allied” in his time, but if he were alive today, it’s easy to imagine that the man so used to living on the edge, pushing every envelope, would have embraced yet another civil rights challenge.