I recently received this anonymous comment in the suggestion box on M Level:

I recently received this anonymous comment in the suggestion box on M Level:

“Thank you for the graphic novels we have at MSEL, but is it possible to get more of these type of texts? Comics are no longer just for children. In fact, they have become very intelligent and well written…” — A Reader

Too true! There are some really great comics out there, and the selection seems to get better and better every year. And it’s not just the old-school publishers like DC Comics, Drawn & Quarterly, and Fantagraphics that are putting comics on the shelves. Big publishing houses like Pantheon and Random House have finally realized what so many of us have known all along: comics are a visual and textual art form that have a unique and subtle way of communicating stories and ideas. They’re complex, moving, and entertaining.

MSE Library doesn’t have a large collection of graphic novels, I know, but we are buying more all of the time. Here are just a few that came in this month (the starred ones I personally recommend).

*Abandon the Old in Tokyo

Abandon The Old In Tokyo is the second in a three-volume series that collects the short stories of Japanese cartooning legend Yoshihiro Tatsumi. Designed and edited by Adrian Tomine, the first volume, The Push Man and Other Stories, debuted to much critical acclaim and rightfully placed Tatsumi as a legendary precursor to the North American graphic novel movement. Abandon the Old in Tokyo continues to delve into the urban underbelly of 1960s Tokyo, exposing not only the seedy dealings of the Japanese everyman but Tatsumi’s maturation as a story-writer. (Publisher’s description)

Alex

Alex is a thirtyish artist who has retreated from a successful career as an animator in Los Angeles to his forlorn hometown. Depicted as a dog-headed man in a world of humans–symbolic of his alienation from those around him as well as of the anthropomorphic animals he once drew–he spends his days drinking, watching TV, and laboring over drawings he ultimately destroys in drunken despair. Reminders of his unhappy adolescence (devastatingly portrayed in Kalesniko’s Why Did Pete Duel Kill Himself? 1997) surround him in the persons of his childhood pal and only friend, Jerome, whose life is even more pathetic than Alex’s (he still lives at home with his religious-fanatic mother); his high-school crush, who’s returning to town; and his former art teacher, now a homeless alcoholic presaging a similar fate for his rudderless student. Former Disney animator Kalesniko possesses a wonderfully distinctive visual style consisting of delicate but assured line work, simple yet dynamic compositions, and effective variation of panel shapes; perhaps his nearest peer is French comics master Guido Crepax. He expertly deploys that style in the service of a touching, compelling portrait of a life immobilized by personal and artistic frustration. (Gordon Flagg, Booklist)

Aya

Abouet could have just wanted to tell a sweet, simple story of the Ivory Coast of her childhood as a counterpoint to the grim tide of catastrophic news, which is all most Westerners know of Africa. But in Aya, Abouet, along with Parisian artist Oubrerie, does quite a bit more than that, spinning a multifaceted romantic comedy that would satisfy even without any political agenda behind it. Set in 1970, Aya follows the travails of some teenage girls in the peaceful Abidjan working-class neighborhood of Yopougon (which they call “Yop City, like something out of an American movie”), as they strive for love and the right boyfriend. Yop City, as detailed in Oubrerie’s fluid and cartoonish black and white drawings, is a mellow place where disco rules the night and practically the worst thing these girls have to worry about is the disapproval of their parents—or in the case of the quiet title character, criticism from those who wish she were more boy-crazed and less focused on a career. It’s a quick piece of work, but memorable in mood, capturing the country’s brief flicker of postcolonial peaceful prosperity before descending into the modern maelstrom of corruption and violence we know only too well. (From Publishers Weekly)

Cancer Vixen

In 2004, cartoonist Marchetto, a hyperstylish “terminal bachelorette,” was busy capturing “fabulista” humor, in the New Yorker and Glamour. She was engaged to a fabulous guy, perennially cool restaurateur Silvano Marchetto, whose personal style perfectly matched her Manhattan-centric life. If this were fiction, this is exactly when she’d stumble; unfortunately for her, life imitated art, and sure enough, she found a lump in her breast shortly before her wedding. Just as bad, she didn’t have health insurance: her policy had lapsed shortly before the fateful mammogram. Cancer Vixen tells the story of what happens next, and how her inner circle— stylists, gossip columnists, shoe designers and assorted others you’d only find in New York City, rallies round to help her beat the disease and get married on time and in high style. Marchetto wears her best high heels to chemotherapy and remarks on the similarities between her hospital gown and Diane von Furstenberg designs. The fashion details are great fun, drawn in a spare loose style, but it’s the heart of her story, the support and love she gets from her family and friends, that make Cancer Vixen a universal story that’s hard to put down. (From Publishers Weekly)

*De:Tales Stories from Urban Brazil

It is in our nature to be fascinated by identical twins. We watch them whenever possible, captivated by mirror images interacting, moving independently of one another and yet sharing the same mannerisms and speech patterns. Fabio Moon and Gabriel Ba are Brazilian twins who share an award-winning talent for comics and an abiding love of the medium. This collection of short stories features the pair working together, in tandem, or separately – trading off on the roles of writing and illustrating, sharing those roles or flying solo. Brimming with all the details of human life, their charming tales move from the urban reality of their home in Sao Paulo to the magical realism of their Latin American background, living up to the twins’ critical acclaim and proving that they are a talented pair to watch for. (Publisher’s description)

*Sloth

The much heralded Love & Rockets cartoonist turns in his first original graphic novel and it showcases a creator still making vital work after two decades. The story is of young people too creative, too smart and too passionate for the constraints of suburbia. Miguel Serra wakes up from a yearlong coma, slower physically but not mentally. He is literally out of step with the rest of the world, a perfectly disaffected youth. Miguel, his friend Romeo and girlfriend Lita use rock ‘n’ roll, urban legends and sex to feel alive. It leads to a love triangle that complicates things nicely. Hernandez takes a big gamble in the middle of the book by having everyone change roles in the story. It’s unclear at first whether it pays off, but eventually the reader sees the characters from different angles, making the humanity in the story stronger as our sympathies are challenged. Hernandez has been compared to GarcÃa Márquez, and uses heavy symbolism, in this case the image of a lemon orchard, which represents both the unconscious and how plant life makes the rest of the world look artificial. Sloth packs a lot of emotion and complicated storytelling into an unusual tale. (Publishers Weekly)

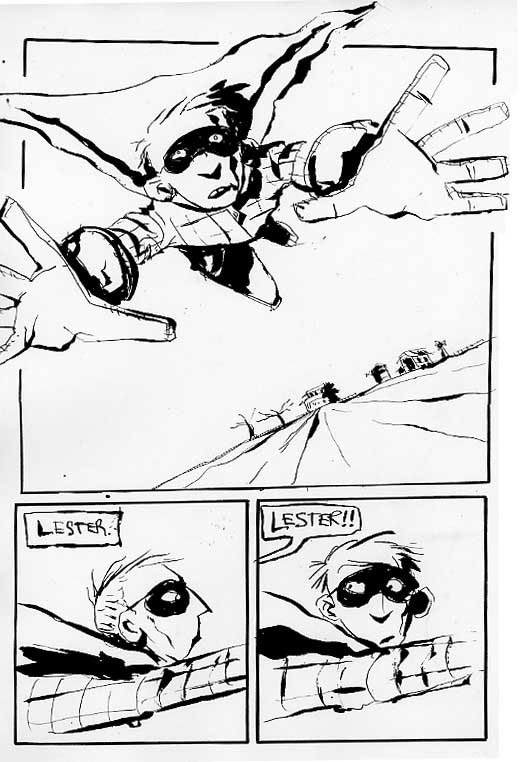

*Tales from the Farm

Ten-year-old Lester, orphaned by his mother’s cancer, lives with his bachelor uncle Ken on a southwestern Ontario farm. He wears a superhero’s mask and cape all day, and he imagines that he has been entrusted with the task of staving off invading space aliens. Ken is making allowances for the boy, but he’s clearly uncomfortable with Lester’s preference for solitary play and comic books. It’s Jimmy, who runs the nearby gas station-convenience store, who reaches out to Lester, participates in his alien-invasion fantasy, and brings him back to the world. Lemire enriches this rather familiar scenario with telling, particularizing detail, ensuring that this time the old heartwarming routine is unforgettably special. Books like this are the reason alternative-comics publishers such as Top Shelf exist. Lemire uses an utterly personal, idiosyncratic drawing style, rough but completely clear, that even just-off-mainstream publishers, such as Dark Horse, would insist on gussying up for publication (in fact, though, Lemire’s art resembles the jagged, blocky look of Mike Mignola’s–and Dark Horse’s–Hellboy). The simple story’s slice-of-life lyricism, sparked by magic realism, is too art-house-movie-ish for the mainstream. But it works. (Ray Olson, Booklist)

We Are on Our Own

A stunning memoir of a mother and her daughter’s survival in WWII and their subsequent lifelong struggle with faith. In this captivating and elegantly illustrated graphic memoir, Miriam Katin retells the story of her and her Mother’s escape on foot from the Nazi invasion of Budapest. With her father off fighting for the Hungarian army and the German troops quickly approaching, Katin and her mother are forced to flee to the countryside after faking their deaths. Leaving behind all of their belongings and loved ones, and unable to tell anyone of their whereabouts, they disguise themselves as a peasant woman and her illegitimate child, while literally staying a few steps ahead of the German soldiers. We Are on Our Own is a woman’s attempt to rebuild her earliest childhood trauma in order to come to an understanding of her lifelong questioning of faith. (Publisher’s description)

Enjoy!!

It’s good to see someone acknowledging the creativity and talent that goes into these books! So many times I have been scoffed at by artists when trying to show them how fantastic some of these comics are.

“A Reader” is mixing up comics and the 2 main types of graphic novels. Graphic novels were usually compilations of comic issues, often covering specific segments of a storyline. The graphic novels “A Reader” is likely referring to, illustrated novels, have always been well written and drawn and inked and typeset. They had to be and being $10-$20 each, they were not for “children”. As for the intelligence of graphic novels and “A Reader”, I’ll simply quote Mark Twain…

“When I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.”