Enjoy this post by Storrie Kulynych-Irvin, one of our 2024-2025 First-Year Fellows. Applications are now open for the 2025-2026 cycle!

In this post I will be picking up and expanding on the main theme of my previous post. There we meet Scaramella, the faithful guard dog, that barked in Latin as it were while protecting the books of his master, the German humanist Jacob Locher (1471-1528). We translated Scaramella’s Latin epigram, where we were introduced to the two sides of an academic debate: the Scholastics and clerics (denigrated as Mules) versus the Humanists (friends of the Muses), represented by Locher: Hoc Scaramella loquor: mulas preponere musis, audax est vacuo iudicat et cerebro. “I am Scaramella and I declare: to place mules before muses is audacious and one makes that decision with an empty mind.”

These words came at the end of Locher’s pamphlet of 1506 in the JHU Special Collections and were actually pretty tame compared to the words of Locher himself. Below, I’ve included my translations of further selections from Locher’s work.

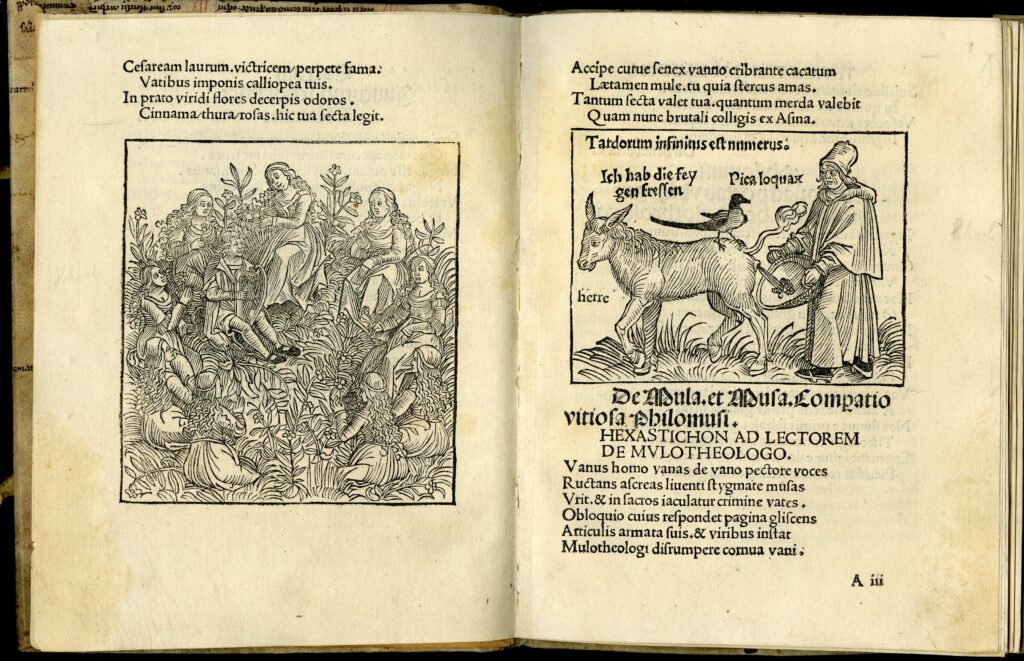

The left-hand page shows us Locher the poet with his harp surrounded by the Muses of antiquity. In that fragrant field of poetry, we read:

Caesarem laurum victricem perpetae famae

vatibus imponis Calliopea tuis.

In prato viridi flores decerpis odoros

cinnama, thura, rosas hic tua secta legit.

“Calliope, you place the victorious Imperial laurel wreath

of lasting fame upon your poets.

You pluck the fragrant flowers in the green meadow

here your followers select cinnamon, frankincense, and roses.”

Locher here aligns himself with the Muses, and the reference to the Imperial laurel shows us that Locher was particularly proud of being a Poet Laureate of the Holy Roman Empire. The right-hand page, by contrast, is pretty vulgar and is accompanied by a highly satirical woodcut of a Scholastic collecting his ‘knowledge’ from the backside of a donkey, illustrating just how low Locher’s opinion was of their work:

Accipe curve senex vanno cribrante cacatum

laetamen mulae, tu quia stercus amas.

Tantam secta valet tua, quantum merda valebit,

quam nunc brutali colligis ex asina.

“Bent over old man, receive the excrement pushed from the mule

into your leaking basket, for you love such dung.

It is worth as much to your sect as feces will be worth,

which you now collect from a dull ass.”

Within the small frame of the woodcut, we can also read: “Tardorum infinitus est numerus.” “The number of stupid men is infinite.” The “Pica loquax” or “mocking bird” is surely poking fun at the scholastic with his leaking basket and his pedantic spectacles. The donkey (labeled “Herre”) seems to only speak a crude German (compare Locher’s learned Scaramella reciting Latin in the previous post) saying: “Ich hab die Feygen fressen” “I have eaten plenty of figs (a laxative!).”

In today’s university we have many fora for debates. Besides in-person, we have newspapers, blog posts, podcasts, etc. But what about the early modern university? I learned through my research that, less than a decade after the printing press became widespread, pamphlets were a heated medium for argument in German universities – to such an extent that these debates were called “pamphlet wars.” This academic infighting pitted different sects of faculty and students against each other, but we can see from the above verses and woodcuts, just how creative and biting the satire could become.

Scholars have unpacked much of the background and players behind Locher’s work. James Overfield’s book Humanism and Scholasticism in Late Medieval Germany (Princeton, 1984) outlines how in 1503 Locher was at the University at Freiburg. There he wrote a diatribe against another professor, George Zingel. It is unclear what sparked the conflict as the two had been on friendly terms previously. Locher called Zingel “the most passionate enemy of the poets,” and a “raving Occamist.” He described Zingel as a devilish liar who was opposed to poets, any innovations within the university, and Locher himself. Locher went so far as to claim that Zingel had interfered with his courses, turned the university council against him, and even hired sixty-six men to murder Locher. It is probably prudent to doubt the full truth of these claims, but they ultimately highlight the prominent controversies in early modern universities between Locher’s newer ideas based in humanism and secular poetry versus those of older scholastics and professors. Thankfully, as Overfield writes, much of this invective sputtered out and “soon the work became less an ad hominem attack than a general criticism of scholastic theology (p. 196).” The satirical neo-Latin, which we first experienced with Locher’s faithful guard dog Scaramella, now takes on more nuance and even more bite in Locher’s own hands and we gain so much more by looking at the original Latin here.