Enjoy this post by Meenal Srivastava, one of our 2024-2025 First-Year Fellows. Applications are now open for the 2025-2026 cycle!

Hi everyone! My name is Meenal. I’m a rising sophomore at the Johns Hopkins University, originally from Phoenix, Arizona, majoring in Neuroscience and minoring in Writing Seminars. As a First-Year Fellow, I’ve had the opportunity to conduct research in the Sheridan Libraries’ Special Collections since the fall semester. My project focuses on counter-cultural ephemera from the 1960s, with a particular emphasis on the exchanges between American and Indian poetry. This journey has been surprising, intellectually rich, and at times deeply personal. I’m incredibly grateful to my mentor, Heidi Herr, who has championed my growth, helped me trust my voice as a writer and researcher, and unearthed fascinating primary sources that have anchored this project.

My research centers on the Hippie Trail—a loosely defined travel route that brought hippies from the West (primarily the U.S. and Europe) into Southeast Asia during the 1960s and 1970s. While most histories of the trail focus on the spiritual and recreational motivations of Western travelers, I became more interested in what was exchanged along the way: books, rituals, values, poems, letters. The travelers were not just on a physical journey but on an ideological one, seeking something they believed the East could offer: escape from Western materialism, spiritual depth, and, in many cases, authenticity.

Writers of the Beat Generation, such as Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder, helped set the ideological foundation for this movement. In the City Lights Journal No. 1, Ginsberg’s poem “In India” recounts his arrival in Calcutta in 1962: “All the hip rituals in U.S. involving pot have been developed and institutionalized here—it’s like seeing a miniature photo enlarged so you can recognize all the details.” He goes on to draw parallels between yogic practices and pot smoking: “There seems to be emerging a definite relationship between pranayama breath control yoga & the practice of pot smoking.”

What Ginsberg saw in India wasn’t foreign; it was familiar. The beatnik ethos he had helped foster in the U.S. was, to him, mirrored by the mystics and ascetics of the East. But what began as a personal spiritual journey quickly became a site of artistic and political connection when Ginsberg encountered a group of Bengali poets known as the Hungryalists.

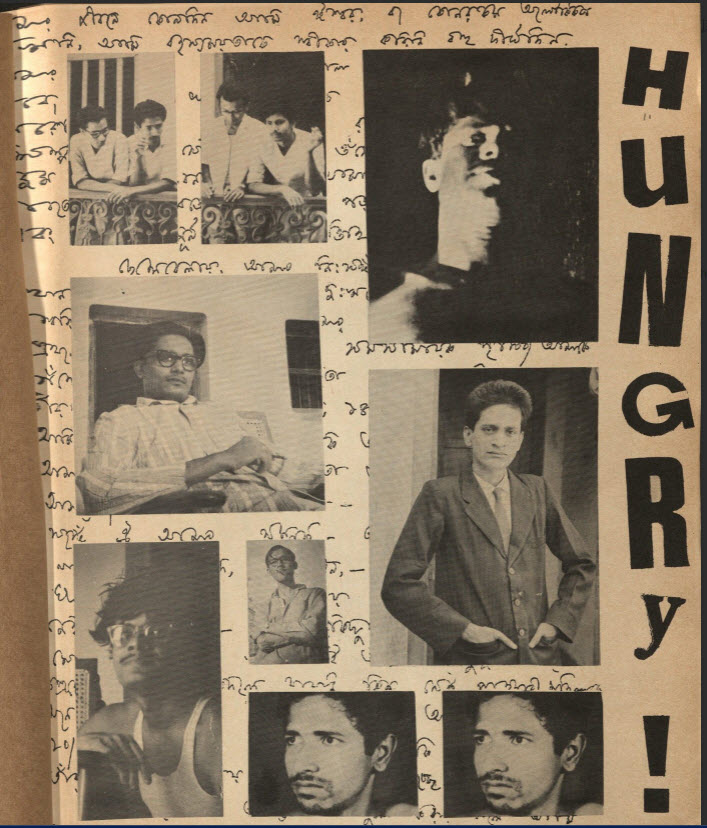

The Hungry Generation—launched by Shakti Chattopadhyay, Malay Roy Choudhury, Samir Roychoudhury, and Debi Roy—was an avant-garde literary movement that emerged from the chaotic post-independence reality of Kolkata. In their 1961 manifesto, the Hungryalists declared that existing Bengali poetry lacked “that scream of desperation of a thing wanting to be man, the man wanting to be spirit.” They rejected dominant poetic genres such as surrealism, realism, and stream of consciousness, aiming instead to present the raw image in its purest form.

Perhaps due to their shared ideals, the Hungryalists and the Beats developed a kinship of sorts during their few months together in India. As such, the Beats and other American Counterculturalists did a lot of excellent work for the Hungryalist movement in two ways: fundraising and marketing. When Malay Roy Choudhury was tried in court on charges of obscenity for his controversial poem Prachanda Boidyutik Chhutar (Stark Electric Jesus), Ginsberg, Snyder, and others quickly mobilized, raising funds through literary journals like Salted Feathers, a Portland-based countercultural journal that donated all profits to the Hungryalists. Ginsberg contacted countless literary VIPs for donations, such as editors, novelists, and cultural figures, including members of the Congress for Cultural Freedom. The Beats also helped coordinate publication efforts in America and Europe, such as the poetry anthology Intrepid, which distributed Bengali poetry alongside works by Western countercultural writers to its American audience.

While the support of the Beats–and especially literary giants like Ginsberg–helped legitimize the Hungries in the eyes of the Western literary establishment, it came with a cost. The Hungryalists were, at times, marketed as the “Indian branch” of Beat poetry, rather than as a uniquely Indian, independent movement. One quote from Gary Snyder is especially telling–in a holograph letter published in Salted Feathers, Snyder claimed that “Ginsberg really developed those boys [the Hungryalists], he is the one actually responsible for turning them on.” This framing—though perhaps intended to show camaraderie—undermines the intellectual independence of the Hungryalists. In fact, they were not simply a derivative movement. As Malay later clarified in an interview with Evan Kennedy: “You think that a family living in a slum would know about Baudelaire? We did not even read Ginsberg’s Howl or other books by Beats.”

The Hungryalists were not inspired to form by Ginsberg; they were inspired by Kolkata—by the squalor, the refugee crisis, the violence of partition, and the failure of institutional religion to address existential chaos. I was curious as to why the Beats and other American Counterculturalists may have fallen into this pattern of misleading advertising. Well, according to historian Steven Bolleto in his article on the Revolt of the Personal in 1960s and 70s Kolkata, emphasizing this point helped the Beats show to their Western peers an “international, diffuse Beat sensibility.” In a way, that makes sense–what better way to advertise your own poetry movement than to convince the literary establishment that your poetic influence is so widespread that it inspired the formation of another poetry movement as far away as west Bengal?

Another point I was curious about was how this foreign involvement with the Hungryalist countercultural movement was receiving in India. In his article published in the arts magazine Avant-Garde, Malay recounts how his obscenity trial revealed the suspicious attitudes that other Indians held towards foreigners, and especially towards the American poets he was meeting. During the police interrogation, the officers asked him questions such as “Which foreign government is paying you?…Where is your underground printing press? What sort of relation do you have with the Americans who visit you often?” Then they searched his house and found City Lights Journal 1 and asked if Allen Ginsberg, who is pictured on the front cover, “was that chief CIA spy who had recently toured India in disguise.” In the trial itself, when famed Bengali poet Tarun Sanyal defended Malay’s artistry by comparing his poetry to Whitman’s, the prosecution declared, “This court is not ready to tolerate any foreign poet. Ours is a different culture, far superior to that of the West.”

Malay then went on to lose the case.

In the West, foreign engagement legitimized the Hungryalists; in India, it alienated them from the true target audience of their counter-cultural movement: their fellow countrymen. The Hungries faced much ridicule about their involvement with the Beats in particular; one-anonymous Hungryalist even wrote in Salted Feathers, “We often hear that we are Beat cultists, that we have taken literature on loan from foreigners… That we fully accept this foreignness—and so on.”

This tension—between transnational recognition and local rejection—has become central to my understanding of cultural exchange. What began as an inquiry into hippie travelers and drug rituals evolved into a much deeper examination of how the perception of counter-cultural poetry movements is shaped by who controls the narrative being distributed in literary circles. Moving forward, I hope all of my readers are able to take away an impression of how important it is to consider the consequences of foreign involvement in –and misrepresentation of–the countercultural movements of developing, newly independent countries like India.

Going into this project, I was unsure of what I’d find or if I’d even be able to see this project all the way to the end. However, over this past year, I have had the opportunity to present my research twice: once during a round-table presentation with library staff and fellow First-Year Fellows in the Macksey Room of the Brody Learning Commons, and again at the Friends of the Libraries Annual Meeting held in the George Peabody Library. I’m also thrilled to share that I will be presenting this project at the American Historical Association Annual Conference in Chicago in January 2026. This research is still a work in progress, but I’m excited to see where it goes over the next year!