Enjoy this post by Storrie Kulynych-Irvine, one of our Special Collections First-Year Fellows for the 2024-2025 academic year.

My name is Storrie Kulynych-Irvin, and I’m excited to be working as a First-Year Fellow. My project involves translating and analyzing a series of neo-Latin texts, under the guidance of my mentor Paul Espinosa. When I took classics in high school, my curriculum focused on standard Classical Latin texts written by authors such as Caesar, Vergil, Catullus, and Horace.

With this project, I have the opportunity to delve into Latin written about 1,500 years after the lifetime of those famous Romans. Before I began the fellowship, I knew that religious texts, and some scientific ones, were written in Latin during the Middle Ages and early modern period. What I didn’t know was the extent to which Latin was still an active language over a millennium after its ancient heyday. In his book Latin: Story of a World Language (Harvard, 2013) classical philologist Jürgen Leonhardt writes that “the quantity of post-Roman texts is so extensive that it exceeds the total of all extant classical Latin texts by a factor of ten thousand (p. 2).” It wasn’t just monks and nuns who wrote or copied Latin; other well-educated people used it as their language of communication, like doctors, professors, theologians, scientists, philosophers, and jurists. In large part, neo-Latin is still under-researched, but it is now undergoing more thorough investigation.

It is common knowledge that the rediscovery and renewed interest in classical texts played an important role in the spread of the Renaissance and Reformation. Latin, of course, was still active before this rediscovery, from the early days of the church through the Carolingian period. The texts favored and emulated during the Renaissance were the ancient Classical ones, particularly the works of Cicero, who was considered the best model. But the Middle Ages also saw stylistic deviations from the Ciceronian style – for example, in the works of Scholastics like Thomas Aquinas. Medieval Latin poetry shifted its rhythmic patterns and began to include end rhymes, though schools still taught the rules of classical meter. Yet Latin’s core grammatical rules remained intact. Rather than being quickly replaced by the evolving vernacular languages, Latin evolved alongside them, and many authors wrote in both Latin and their vernacular. In fact, Leonhardt notes that until at least the 15th century, “more literature was produced in Latin than in each of the national languages (p. 5).”

Even when and where vernacular literature developed, Latin continued to flourish. My first translation is proof: a pamphlet printed in 1506, written by the humanist Jacob Locher. He was born around 1471-4 in Ehingen in southern Germany, and spent most of his career at the University of Ingolstadt. In 1497, Emperor Maximilian I named him a Poet Laureate of The Holy Roman Empire. Locher was perhaps best known for his translation from German into Latin of Das Narrenschiff (“The Ship of Fools”) a popular 15th-century satire, by Sebastian Brandt. The work of Locher’s that I’m translating doesn’t have a specific title per se: the title page just lists the different contents under the heading, Continentur in hoc opusculo a Jacobo Philomuso facili syntaxi concinnato …, (“The following [titles] are contained in this little work, elegantly written in a easy-to-follow manner by Jacob Locher, a Devotee of the Muse”). What follows is a series of satirical poems and polemics illustrated with intriguing and humorous woodcuts. Throughout the work Locher, on the side of the humanists, refutes criticisms coming from his academic rivals, the scholastics and clerics of the Church. The humanists looked back to poetic and secular examples of Latin, while the scholastics relied on the more stilted and esoteric Latin of the schools of Logic and theological debate.

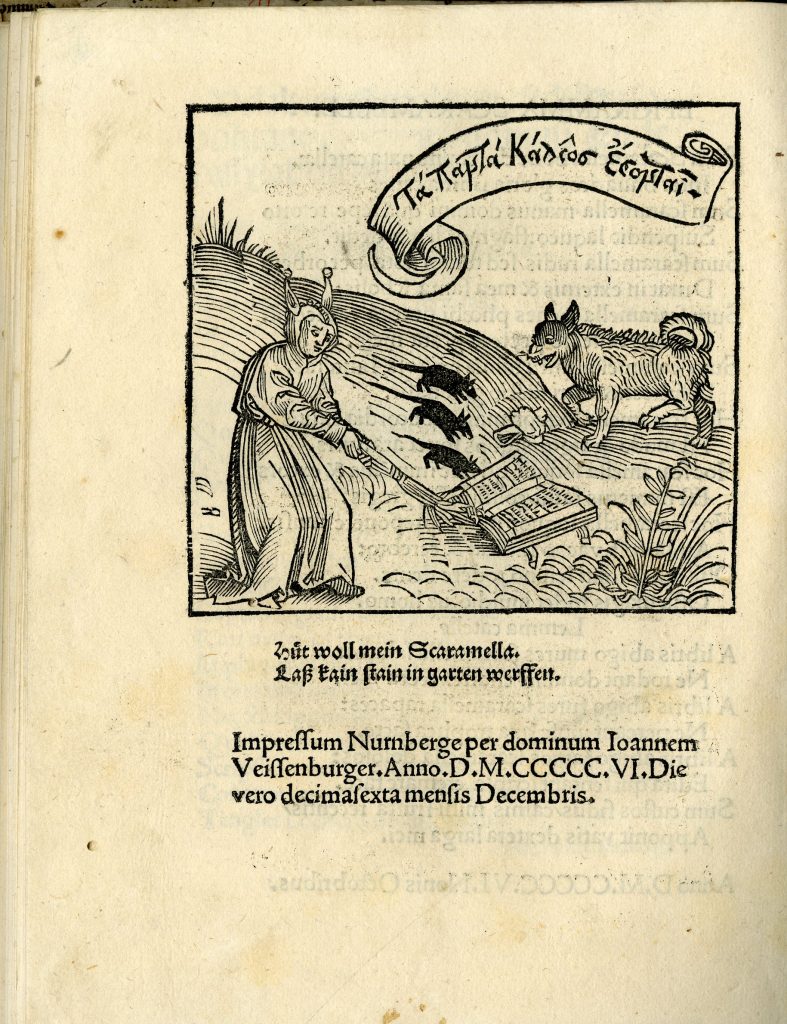

The text I translated actually comes at the end of the pamphlet. It is an epigram for Scaramella, Locher’s faithful dog, who compares the two sides pitted against each other: the poets and humanists such as Locher (companions to the Muses) versus the clerics and scholastics (compared here to stubborn mules). The woodcut beneath the verses shows Scaramella driving off jealous mice and fools attempting to gnaw away and set fire to his master’s books.

Epigramma Scaramellae

Sum Scaramella bona de semina nata catellae,

inter bavaricos gloria prima canes.

Sum Scaramella, manus domini, quae saepe retorto

suspendit laqueo, flagraque lenta dedit.

Sum Scaramella rudis, sed totum nota per orbem

durat in externis et mea fama scholis.

Sum Scaramella, penes Phoebi nutrita cathedram.

Lusibus oblecto pectora grata meis.

Sum Scaramella, mihi nimis exitiosa simultas

displicet et clari factio gymnasii.

Hoc Scaramella loquor: maior concordia brutis

est modo quoque rigidis, quos fovet ara, viris.

Hoc Scaramella loquor: quod nunc immensus et excors

est numerus fatui colluuiesque gregis.

Hoc Scaramella loquor: mulas preponere musis

audax est vacuo iudicat et cerebro.

Ossa canes soliti ieiuno rodere dente,

ossa magis rodet invidiosus homo.

An Epigram for Scaramellae

I am Scaramella, born from the good seeds of a young dog

the prime glory among German dogs.

I am Scaramella, the hand of my master, which often

holds up my twisted leash, gave me a gentle lashing.

I am Scaramella, a bit wild, but well-known through the whole globe,

and my fame endures in foreign schools.

I am Scaramella, nourished under the seat of Phoebus Apollo

I amuse my agreeable soul with my games.

I am Scaramella, an overly dangerous feud and a faction

from the famous gymnasium upsets me.

I am Scaramella and I declare: there is lately greater

concord among dull as well as stern people, whom the Church favors.

I am Scaramella and I declare: the fact is that the number and dregs of the foolish crowd

is immense and beyond comprehension.

I am Scaramella and I declare: to place mules before

muses is audacious and one makes that decision with an empty mind.

Just as dogs have grown accustomed to gnaw bones with hungry tooth

so the envious man gnaws at bones all the more.

Lemma catellae

A libris abigo mures Scaramella salaces,

ne rodant domini chartea tecta mei.

A libris abigo fures Scaramella rapaces,

ne pereant musae fixa trophea sacrae.

A libris abigo fatuos Scaramella dolosos,

edita qui tentant scripta cremare face.

Sum custos fidus, carnis mihi frusta recentis

apponit vatis dextera larga mei.

A Concluding Note from the Dog Himself

I, Scaramella, drive the hungry mice away from the books,

in order that they not nibble the covered books of my master.

I, Scaramella, drive rapacious thieves away from his books,

so that the established prizes of the sacred muse may not perish.

I, Scaramella, drive away from his books the cunning fools,

who attempt to burn the published writings with a torch.

I am a faithful guard, the generous right hand of my poet

places pieces of fresh meat before me.