In earlier posts, I talked about reprocessing the Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve papers and how that work led me to Fannie Manning Gildersleeve Tonsler, a Black woman from Charlottesville, Virginia, who was Gildersleeve’s daughter. Now that I’ve set the stage, I want to give an overview of what I’ve learned about Fannie from some of the public records that mention her and the conversations I’ve had with people who are also interested in learning more about her life.

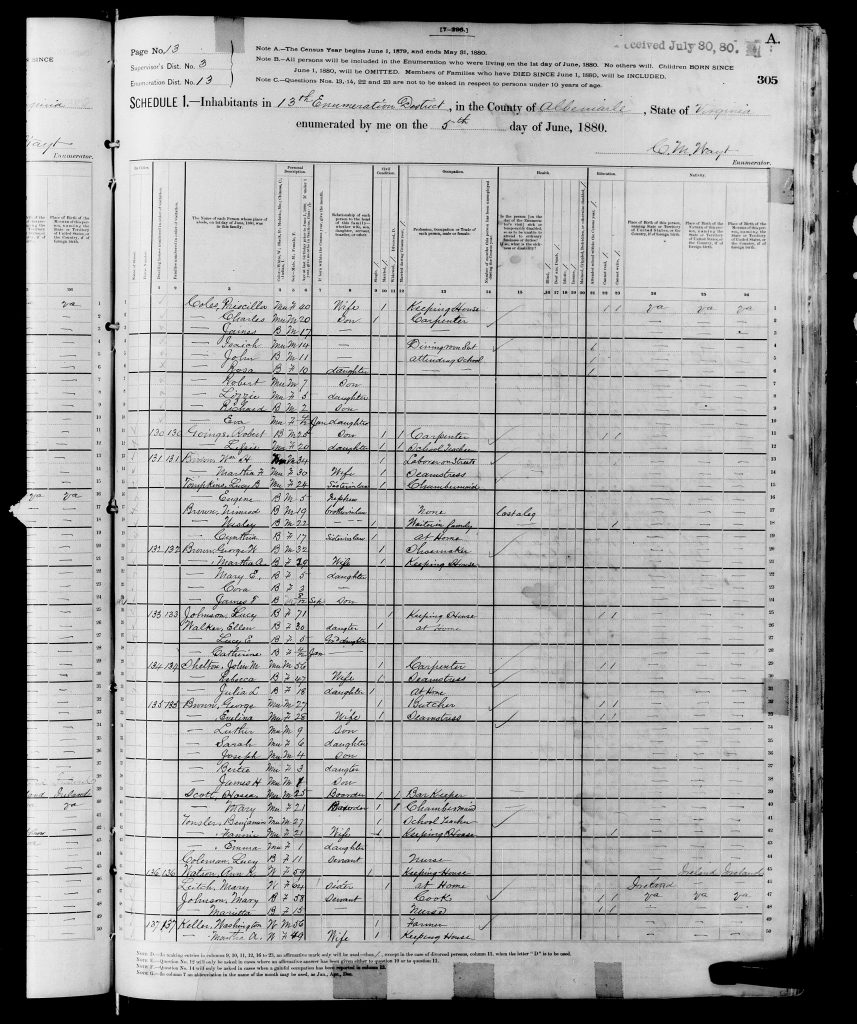

Based on information in the 1880 U.S. Census, Fannie Tonsler was probably born in 1859 or 1860. Her State of Virginia death certificate lists her birth year as 1869, but this seems highly unlikely, given that she was married in 1876 and had a one-year-old daughter in 1880 (as classicist Judith Peller Hallett notes in a footnote in her conference paper “Ultra veritatem muliebris vis: women classicists at and beyond Washington University in the dawning of post-bellum America”, 6). It seems likely that Fannie was born in the Charlottesville, Virginia area (although Richmond is close enough that it is also a possibility, and a secondary source that I mention later says that her origins were in England), and given the time and place, the odds are that she was born enslaved.

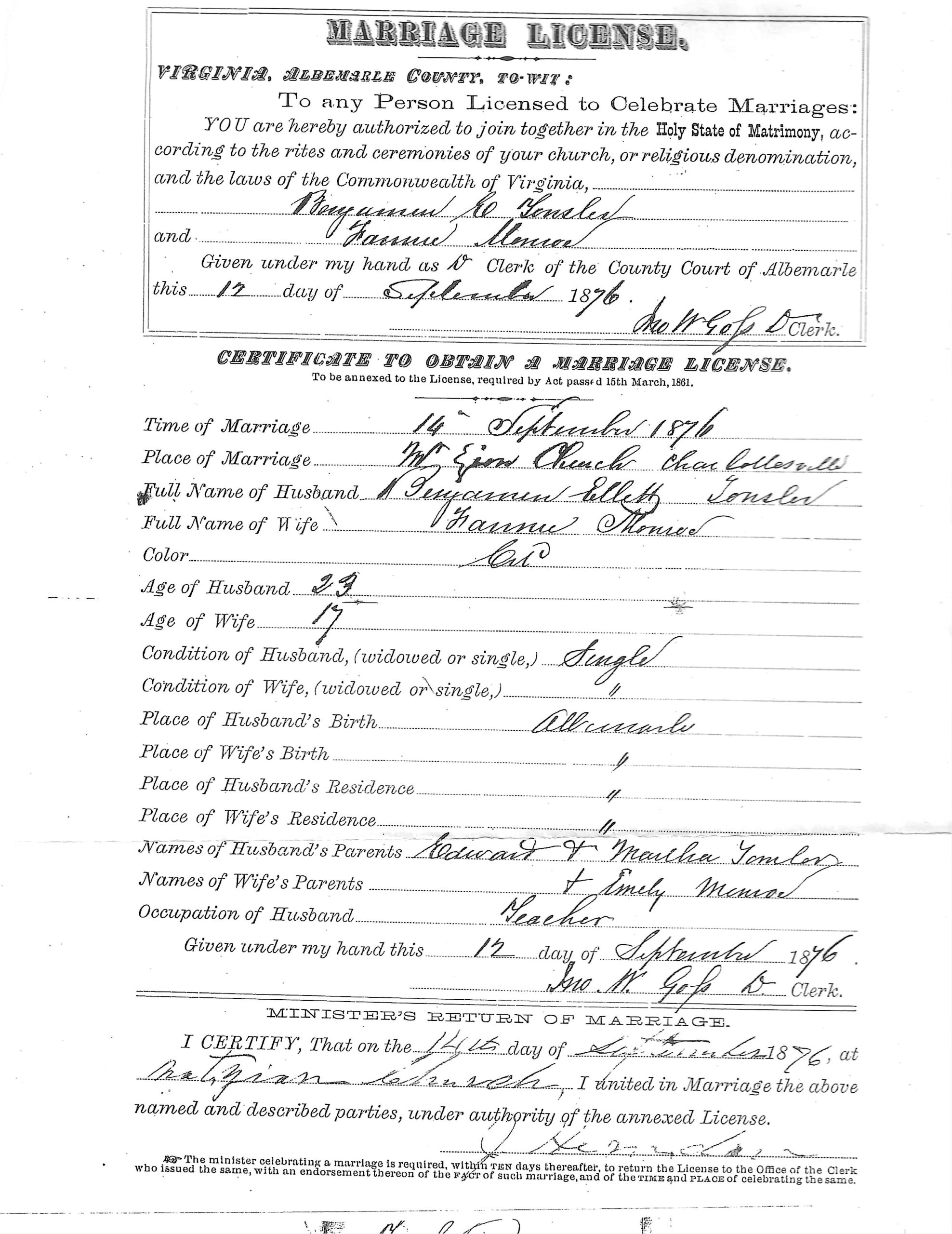

So far, I have seen very little information about Fannie Tonsler’s mother. Susan Oberman, a former resident of Charlottesville, VA who did genealogical research on Benjamin Tonsler, shared a copy of Benjamin and Fannie Tonsler’s marriage license (dated September 17, 1876) with me. This is the first instance that I am aware of where Fannie definitively shows up in a public record, and it is also the only place I have seen her mother’s name listed. In this document, her mother’s name is written as Emily Monroe, and no father’s name is given.

Marriage License, Benjamin Tonsler and Fannie Monroe, “Tonsler” Vertical File, Albermarle Charlottesville Historical Society Library.

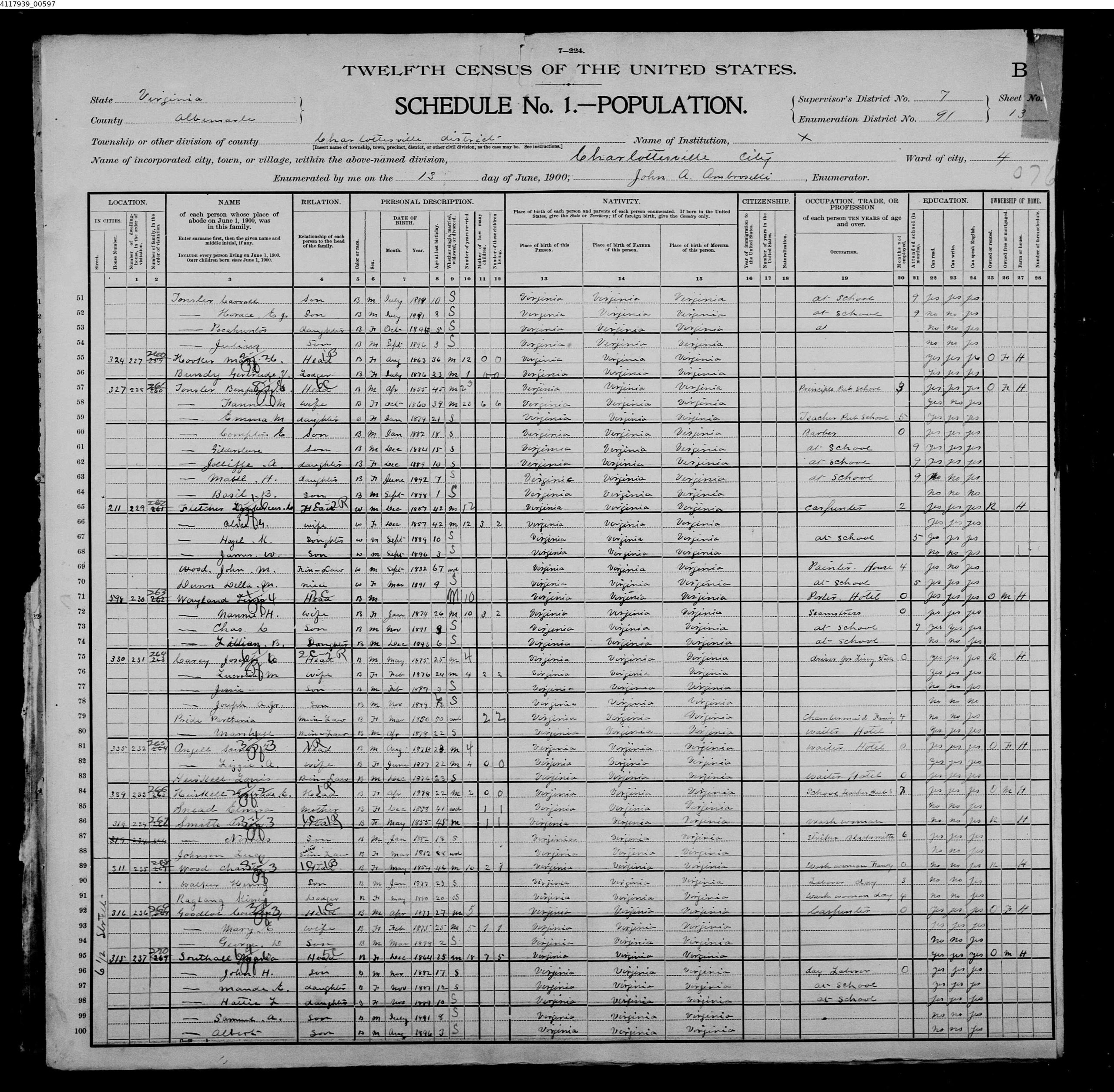

By 1880 (according to the U.S. Census), the Tonslers had a one-year-old daughter, Emma. Most records from the 1890 census were lost in a fire in 1921, but by the next Census in 1900 (when Fannie was around 41) the Tonsler household consisted of 8 people, Benjamin and Fannie Tonsler and their six children. The Tonslers’ daughters were Emma (21), Jolliffe (10), and Mabel (7), and their sons were Compton (18), Gildersleeve (15), and Basil (1). Gildersleeve and Basil Tonsler’s names clearly connect to their white, former Confederate soldier grandfather, but some of the Tonsler’s other children’s names also have connections to the Gildersleeve family and to Johns Hopkins. Emma was the name of Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve’s mother, and it was also the name of his only daughter with his wife. While Emma is a relatively common first name, Jolliffe is not. One of Johns Hopkins the founder’s brothers, Samuel Hopkins, married a woman named Lavinia Jollife, whose father was an enslaver from the Winchester, Virginia area (See William Jollife’s Historical, genealogical, and biographical account of the Jolliffe family of Virginia, 1652 to 1893, 102-107 for more information on Lavinia Jolliffe’s family, which included both enslavers and abolitionists). These names of the Tonslers’ daughters could be a coincidence, but it’s hard not to speculate that they may have some link to the Gildersleeve and Jolliffe families.

“United States Census, 1900”, Charlottesville District, Charlottesville city, Ward 4, ED 91, Albemarle, Virginia, United States, Sheet 31B, database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MMJJ-9WD : 10 March 2022). The entry for the Tonsler household begins on line 57 (seven lines down).

The Preservers of the Daughters of Zion Cemetery, the historically African American cemetery where several members of the Tonsler family (including Benjamin and Fannie) are buried, have an excellent website with a page about Benjamin Tonsler and his role as an educator in Charlottesville’s late 19th and early 20th century Black community. Interest in education clearly ran in the Tonsler family – Emma Tonsler was listed as a teacher in the 1900 census, and all of the other children of school age are listed as in school. Poignantly, in the same census, Fannie is listed as able to read but not able to write, suggesting that she did not have the same educational opportunities as her husband and children (and all the more heartbreaking given that her father Basil Gildersleeve was fluent in so many languages). A book from the “Images of America” series, Charlottesville: An African-American Community by Agnes Cross-White, contains photos of Benjamin and Fannie, Emma, Basil, and Mabel Tonsler, all of which can be seen in the Google Books Preview. The photos came from Tonsler descendant Elmer Sampson, and interestingly, the caption on Fannie’s photo says that she “originally came to the United States from England” (Cross-White, 10). I have seen no other source linking Fannie to England, but that doesn’t mean that the connection isn’t there.

When my colleague Monica Blair and I were in Charlottesville for the fall 2022 Universities Studying Slavery Conference, Edwina St. Rose and Bernadette Whitsett-Hammond, two leaders of the Preservers of the Daughters of Zion Cemetery, generously gave us a tour and showed us the graves of Benjamin and Fannie Tonsler and some of their children. Fannie died on June 8, 1937, and her name on her gravestone reads “Fannie Gildersleeve Tonsler.”

Fannie Gildersleeve Tonsler’s grave in the Daughters of Zion Cemetery, Charlottesville, Virginia. Photo by Liz Beckman.

Frustratingly, as you might have noticed, the documents I described that outline Fannie Tonsler’s life are mostly from the perspective of various government bureaucrats (with the exception of the photo that came from her family), and they are light on the details of what her childhood, marriage, and family life were like. This is one of the great failings of archivists and the archival record that we have shaped: more detailed records created by people who were not some combination of white, male, and wealthy often were ignored by archivists and the institutions who employ us, or those people simply may not have had the resources (like being able to write) to create records in the first place. In my final post in this series, I will discuss the questions I still have about Fannie, and speculate about some of the answers and some of the leads I would like to follow up on.

Sources:

Cross-White, Agnes. Charlottesville: An African American Community. Dover, NH: Arcadia, 1998. https://books.google.com/books?id=zItuPDQoXcAC&newbks=0&printsec=frontcover&pg=PA10&dq=Fannie+Gildersleeve+Tonsler&hl=en#v=onepage&q=Fannie%20Gildersleeve%20Tonsler&f=false. Accessed July 10, 2023.

Daughters of Zion Cemetery. “Tonsler, Benjamin Ellis.” https://daughtersofzioncemetery.org/the-people/tonsler-benjamin-ellis/. Accessed July 10, 2023.

Hallett, Judith Peller. ” ‘Ultra veritatem muliebris vis’: women classicists at and beyond Washington University in the dawning of post-bellum America.” Paper delivered at Washington University in St. Louis, February 2021.

Jolliffe, William. Historical, genealogical, and biographical account of the Jolliffe family of Virginia, 1652 to 1893 : also sketches of the Neill’s, Janney’s, Hollingsworth’s, and other cognate families. Philadelphia: J. Lippincott, 1893. https://archive.org/details/historicalgeneal00joll/page/n115/mode/2up. Accessed July 10, 2023.

Marriage License, Benjamin Tonsler and Fannie Monroe, 1876, “Tonsler” Vertical File, Albermarle Charlottesville Historical Society Library.

United States Census Bureau. “U.S. Census Bureau History: 1890 Census Fire, January 10, 1921.” https://www.census.gov/history/www/homepage_archive/2021/january_2021.html. Accessed July 10, 2023.

“United States Census, 1880,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MCPX-1TY : 15 January 2022), household of Benjamin Tonsler, Charlottesville, Albemarle, Virginia, United States; citing enumeration district , sheet , NARA microfilm publication T9 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), FHL microfilm. Accessed July 10, 2023.

“United States Census, 1900”, Charlottesville District, Charlottesville city, Ward 4, ED 91, Albemarle, Virginia, United States, Sheet 31B, database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MMJJ-9WD : 10 March 2022). Accessed July 10, 2023.