In part one of this blog series, I discussed why processing archivists sometimes reprocess collections. In part two I’ll talk more specifically about reprocessing the Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve papers and give some context for why the papers needed work, how I approached reprocessing, and how perusing Gildersleeve’s Wikipedia page on a whim while looking at his correspondence led to an ongoing research project.

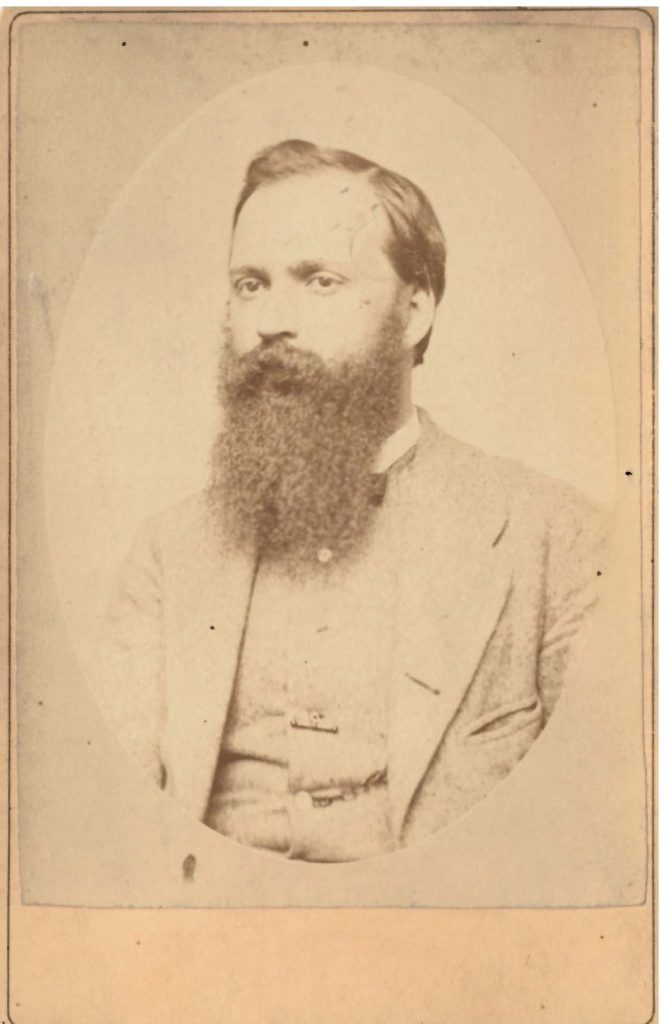

Both academics and non-academics have spilled a lot of ink about Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve in the last 150 or so years (including me, in the biographical note for the reprocessed Gildersleeve papers, which I’ll link to but not re-write here). The essentials to understand for the purposes of my work on his papers are these: Gildersleeve was a 19th century classicist, a specialist in the Ancient Greek language, and one of the first five full professors hired by President Daniel Coit Gillman to teach and research at the newly founded Johns Hopkins University in 1876. He also fought in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War and was, in the words of Dr. Gikandi of Princeton University (Gildersleeve’s undergraduate alma mater) “an unrelenting defender of the Confederacy, states’ rights, and, by implication, slavery” (“Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve,” Princeton and Slavery).

The Gildersleeve papers were therefore an ideal reprocessing project – Gildersleeve had an outsized amount of power to influence how Johns Hopkins University developed in its early years, the first materials in the collection were donated to the library as early as 1915, and the most recent finding aid for his papers was created in 1988 (with an update to the biographical note in 2019 to recognize Gildersleeve’s racism). Most archivists and historians talk about enslaved people, enslavers, the Confederacy, and the Civil War very differently in the 2020s than they did in 1988, let alone 1915. It was past time to comprehensively review the description of the papers and revise it to better reflect Gildersleeve’s beliefs about race, the institution of slavery, and the Confederacy, particularly within the context of Hopkins Retrospective’s Reexamining Hopkins History project and our efforts to reckon with the university’s connections to slavery.

These differences were at the front of my mind as I did a basic survey of the Gildersleeve papers, created a reprocessing plan, and began relabeling folders in the collection. The existing inventory in our collections database (ArchivesSpace) for the first series in the collection, Correspondence, listed the names of individuals and organizations who corresponded with Gildersleeve along with the box in which the correspondence was contained, but the inventory did not include folder numbers or the date range of the correspondence in each folder. I set about correcting this so that the folder titles included dates, box numbers, and folder numbers written on every folder. I also read much more of the correspondence than I usually do when processing a collection in order to make sure that the correspondents listed were accurate and to see if anything in the letters illuminated Gildersleeve and his personal and professional circles’ ideas about race in post-Civil War America, as well as the early years of Johns Hopkins University.

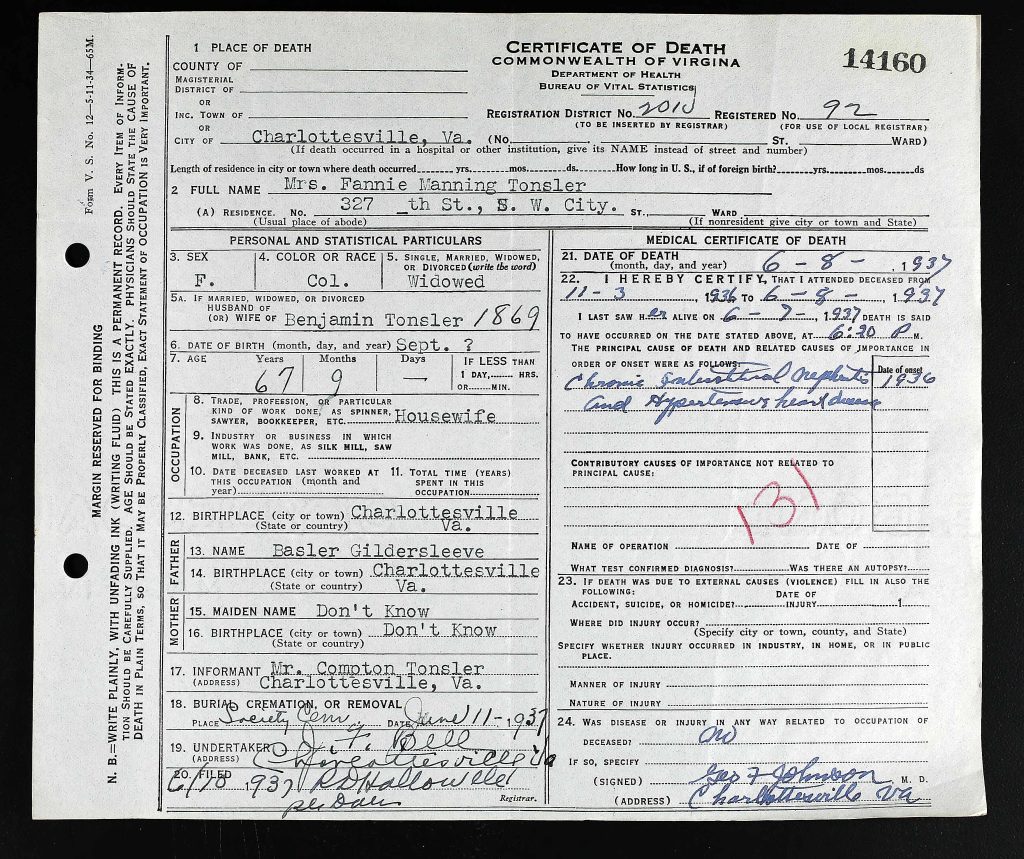

At some point during the often tedious (due to the wide range of legibility in 19th and early 20th century handwriting) process of going through the correspondence, I became curious about what Gildersleeve’s Wikipedia page said about him. What I found on the page changed the trajectory of my Gildersleeve-related research dramatically. At the bottom of the page, under the “Death and legacy” heading, the following two sentences jumped out at me: “Fannie Manning Gildersleeve, a black woman born approximately 1869, lists Basil Gildersleeve as her father on her funeral records. Fannie Gildersleeve was married to Charlottesville, Virginia educator Benjamin Tonsler” (“Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve,” www.wikipedia.org). This information was completely new to me, and I quickly confirmed that it was also new to my archives colleagues, including (now retired) 39-year-veteran Senior Reference Archivist Jim Stimpert. The Wikipedia page includes a citation for Fannie Tonsler’s funeral records, and additional digging by myself and my colleagues made it clear that the evidence for Gildersleeve and Fannie Tonsler’s relationship is there.

For the rest of the time that I spent working on the Gildersleeve papers (and up until the present), I have been trying to learn as much as possible about Fannie Tonsler and her family. I learned important details from current and past members of the Charlottesville community, as well as from classicists, and I have gathered information and public records that outline some of Fannie’s life. In my final two posts of this series, I will discuss what the records tell us about Fannie Tonsler and her husband and children, as well as what questions remain unanswered.