Hi, I’m Elizabeth England, the Digital Archivist for Special Collections here in the Sheridan Libraries, where my job includes activities such as web archiving, transferring digital content off of media like floppy disks and CDs, and ensuring our digital materials are properly preserved so they may be accessible for years to come.

Recently, I was asked by the Society of American Archivists’ Preservation Section to give a version of a talk I gave at the 2018 Society of American Archivists annual conference, but this time formatted for Twitter! This virtual Twitter conference was held under the #PresTC19 hashtag as part of Preservation Week. The conference had a number of 10 minute long presentations, presented as Twitter threads, on a variety of topics related to the preservation of cultural heritage. You can view my presentation below, or click here to view it on Twitter! [To magnify each image here in the blog, simply click it.]

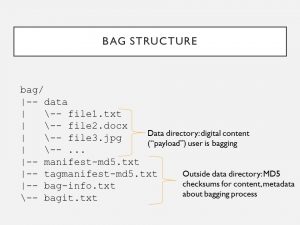

1. I disk imaged a hard drive (thinking it hadn’t been imaged before), used BagIt to package the image as a bag (file packaging convention that places content into sub-directory named “data” & creates files outside the data dir. to document the bag) & put bag in storage #PresTC19

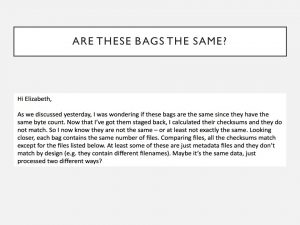

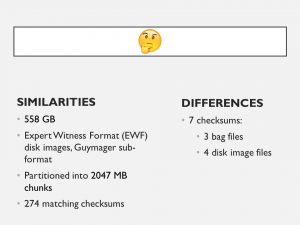

2. A library sys admin noticed my new disk image maybe wasn’t so new after all? Already in storage was a bag with same byte count, same # of files, & almost all checksums matched. Both bags contained an Expert Witness Format disk image created w/ Guymager in @BitCurator #PresTC19

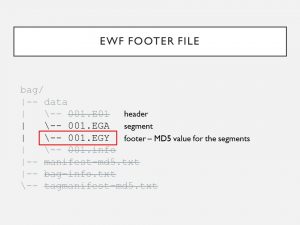

3. Both images were broken into 2047 MB segments (default Guymager setting). The bags had 274 matching checksums & 7 not matching. I took a closer look at those 7 files. Some I was able to eliminate as potential problems because of the nature of the file. #PresTC19

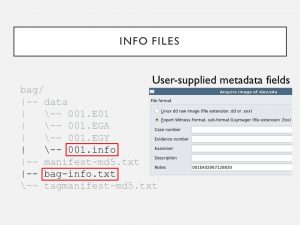

4. The bag-info & disk image info files both contain metadata, such as who performed the work & when, so it made sense the checksums didn’t match for these. When using a format that introduces info such as user-supplied metadata, you won’t get “identical” disk images. #PresTC19

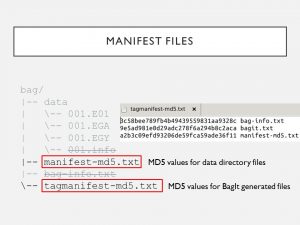

5. I then eliminated the MD5 files. If checksums for files in the data dir. change, then checksums for the manifest-md5.txt files won’t match either because the manifest files are documenting different bitstreams. This domino effect extends to the tagmanifest too. #PresTC19

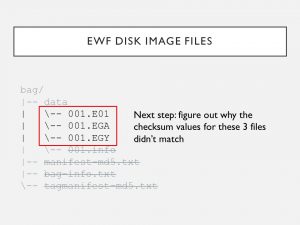

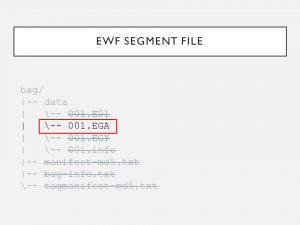

6. I wanted to know why the E01, EGA & EGY files didn’t match, other than a loss of integrity. Integrity means that an object is complete & unaltered in all essential respects. #PresTC19

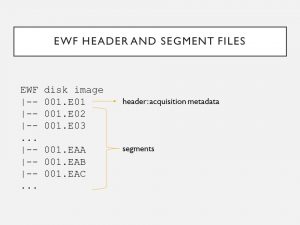

7. Expert Witness Format is a forensic disk imaging format & can break the data into smaller, equally sized partitions. When using EWF, the file name will remain the same but not the file extension: 1st extension is E01 & so on until E99, & then EAA, etc. #PresTC19

8. E01 is the header & contains acquisition metadata (user’s name, date, etc). After E01 are segments, beginning with E02 extension. Segments contain exact copies of the data with checksums for the preceding data interlaced. Segments don’t include acquisition metadata. #PresTC19

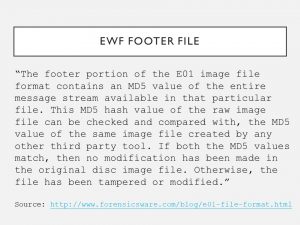

9. EWF images also have footer files. While E01 is consistently the header file, there’s no consistent extension for the footer: it can vary based on the amount of data being imaged, and the size selected for the partitions. In my case, the footer file was EGY. #PresTC19

10. The footer holds a checksum that pertains to the segments but not header. Using EWF to image the same drive 2 separate times partitioned the same way, you’ll never have the same header file but always have the same footer – so long as there’s no data corruption #PresTC19

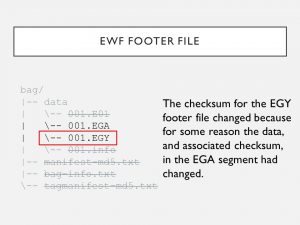

11. In this case, the footer was 1 of the discrepancy files, which is explained by the EGA segment file having different checksums between the two disk image versions. More domino effect. #PresTC19

12. While all 7 files differed from the 1st to 2nd imagings, I reasoned most away through considering user-supplied metadata & cascading effects that a change in 1 file’s bitstream can have on another file. Only the EGA segment indicated a loss of integrity. #PresTC19

13. I believe a small portion of the 558 GB was corrupted in between the 1st & 2nd imagings. For this reason I kept the earlier image as the preservation copy, using the info files to fill in some blanks in the provenance, such as acquisition date. #PresTC19

14. Finally, while disk images are associated with a high-level of transparency about what was on the source media, the way forensic disk images are formatted with added metadata can obscure where meaningful errors may lay. #PresTC19

Conclusion

It was a challenge to get in all the information I felt was necessary with a maximum of 280 characters per tweet, and maximum of 15 tweets total, spread across 10 minutes and required just as much preparation (if not more) than the original presentation! However the response I received indicated that the libraries and archives community enjoyed my presentation and learned something from it, and I hope you did as well. If you have any questions, you can reach me at eengland@jhu.edu.

Author: Elizabeth England, Digital Archivist