This blog post by Earle Havens (Nancy H. Hall Curator of Rare Books & Manuscripts at Johns Hopkins University Sheridan Libraries) is a re-post from the University of St. Andrews’ Preserving the World’s Rarest Books Project, of which the JHU Sheridan Libraries is a member. Preserving the World’s Rarest Books is a new programme, sponsored by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation of New York that aims to put the analytical power of the Universal Short Title Catalogue (USTC) at the disposal of the world library community.

————

This week’s post is by Dr Earle Havens, the Nancy H. Hall Curator of Rare Books & Manuscripts at the Johns Hopkins University. The Sheridan Libraries at Johns Hopkins is one of our Preserving the World’s Rarest Books partners.

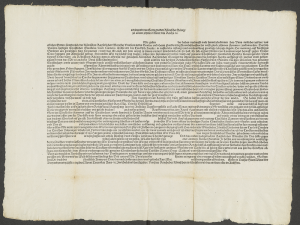

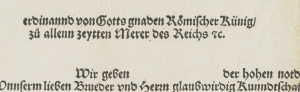

Featured image: Ferdinand I, King of the Romans, Bohemia, Hungary, and Croatia, Holy Roman Empire. [F]erdinannd von Gotts gnaden Römischer Künig … Wir geben der hohen notdurfft nach hiemit züerkennen … das Unns, unsern Lannden … von gedachtem Türken [Vienna, 1536].

The above circular letter was printed as a broadside on extremely durable paper and remains remarkably well-preserved in an uncut, nearly pristine state. It was initially issued from the imperial Viennese printer on 23 December 1536 to notify Ferdinand’s fellow Electors, their vassals, and the Estates of the imperial Diet about military preparations being made by the Turkish Sultan, Suleiman I “the Magnificent” (d. 1566), for yet another impending attack on Christendom. Such an attack would have transpired within a few years of the failed Ottoman Siege of Vienna (1529) and subsequent Siege of Güns (1533).

The imperial order was made after informants of King Ferdinand and his brother, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, reported once more of the distant beat of Ottoman war drums. Such invasion fears were exacerbated by allied concerns over internal dissension among the nobility of Ferdinand’s fissiparous hereditary Hungarian possessions.

This sturdily printed ephemeron called for a new muster of imperial cavalry and infantry to address the looming Ottoman threat well before the summer fighting season, for distribution across the vast territories that formed the eastern marches of the Holy Roman Empire. Perhaps to inspire a clearer sense of confidence in its authenticity and authority, and a more palpable sense of vassal obligations to imperial calls to arms, this broadside was printed on the heaviest paper then available. Such paper stock will have come at a great cost, for its weight was of the sort usually reserved for supporting and preserving large-scale and often extremely expensive maps and copper-plate engravings, rather than simple letterpress.

This was a piece of bureaucratic paperwork, but also a legal instrument meant to last and, quite literally, to make an impression on the interested parties. Its many blanks formed by the letterpress text were to be filled out with relevant dates, names, locations, and other logistical commitments made by its imperial recipients, including ample space for its official notarization (annotations that appear to be present in the British Library exemplar, Gen. Ref. K.T.C.7.b.5). The letterpress blanks also include an ample space for the initial capital “F” in Ferdinand’s name to be filled out calligraphically as a large decorated initial, perhaps even as a portrait illustration, depending on the prestige, taste, and inclination of the recipient.

One of perhaps a half dozen identifiable copies (others include University of Michigan DB 65.3 H6 1536, also blank; and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Library RM IV 966), these legal ephemera rarely survive, and perhaps less often, still, when they were never filled out in manuscript and, thus, never took on the status of a fully executed instrument of law. There might well be other examples completed in manuscript, though perhaps preserved in an unbound legal archival collection, where the letterpress element could be less susceptible to formal cataloguing as an early imprint. Comparison of the Hopkins exemplar with others may reveal further details along these lines.

Should printed administrative documents such as this—richly produced, but for a utilitarian legal purpose—properly count among the “world’s rarest books”? Or are they more common than one might expect, even during this fairly early period in the history of printed ephemera for which survival rates are incredibly low? In an effort to “preserve the world’s rarest books” how capable are we of “preserving the world’s rarest ephemera” in the process? Although we have no record of the broadside’s disposition prior to its acquisition by Johns Hopkins several years ago, the folds in the object suggest that it may well have survived simply by being tipped in between the boards of a larger bound book.

Image Rights: All images in this post are the property of the Johns Hopkins University and may be used and reproduced for non-commercial purposes.