Authored by: Neil Weijer, Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow in Premodern and Early Modern Studies

Books can turn up in unlikely places, as anyone who has spent time wandering around a room musing “it was here somewhere…” is well aware. But in Special Collections, one might turn up inside (or on) another book as part of its binding. In my work on the earliest printed books at the  Peabody, I’ve come across several examples of medieval and early modern recycling at work.

Peabody, I’ve come across several examples of medieval and early modern recycling at work.

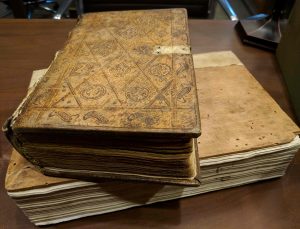

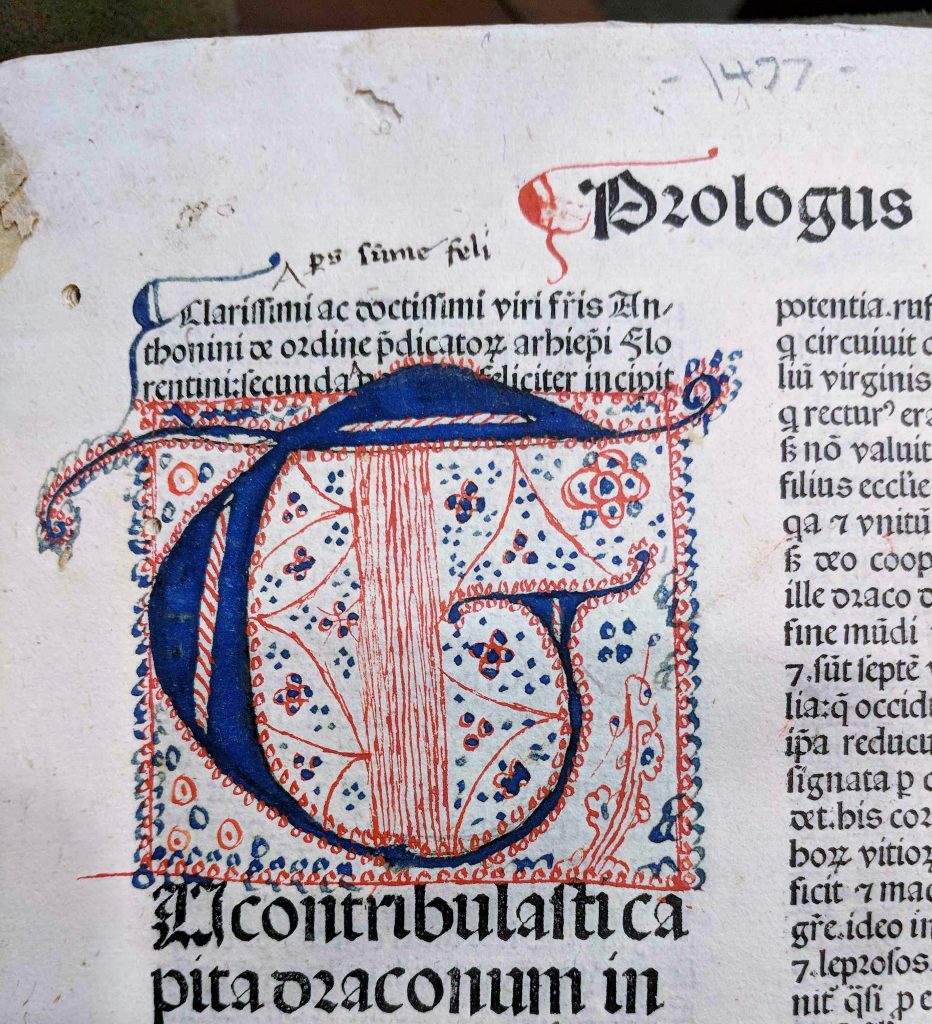

Like the manuscripts they circulated with, early printed books like this treatise on the moral vices by St. Antoninus of Florence (1389-1459) were bound by the communities who bought and used them. Antoninus was a prolific (and encyclopedic) author, so binding a text like this with anything else, even its first volume, would have been a difficult undertaking. The durable wooden boards that make up this binding would likely have included a full covering of leather or other skin, as well as clasps and straps to help hold the book closed and keep its pages flat. The pages would have most commonly been sold as loose sheets by the printer; the readers could therefore customize almost every aspect of their books. The elaborate initial “T” covers up some printed text that needed to be copied back in.

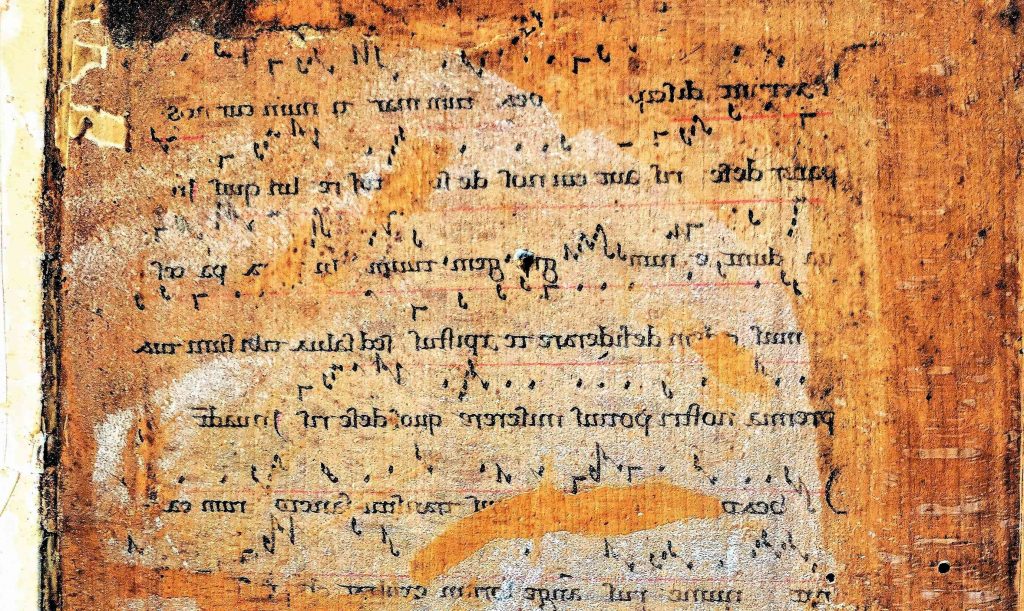

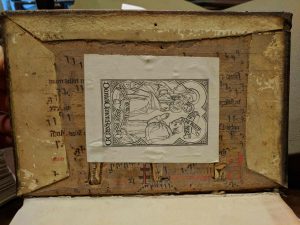

Sometime after its initial binding, this book was given a makeover – perhaps by a new owner. Three quarters of the original binding was cut away to expose the volume’s wooden boards, but opening it up revealed a trace of even earlier material, kept undercover.

Music books such as this one would have been subject to frequent use, as well as the changing of services, and their damaged or otherwise unusable leaves formed part of the arsenal of many pre-modern bookbinders. There’s even evidence that the early musical notation like this may have been recycled for its decorative properties as well as its sturdiness.

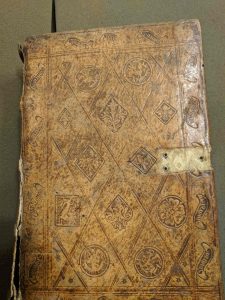

Nor  is this the only early printed book at the Peabody to have an older traveling companion. This volume of late medieval sermons, printed in 1493 in the town of Hagenow on the French-German border, contains two distinct collections, bearing separate title pages and indices, but completed a month apart. The printer may have hoped that the two would be bought as a set, and most are indeed bound this way: the Franciscan friars who owned it first covered it in thick leather, bleached with alum and decorated with stamps and other designs impressed by metal tools. [Image 4: Front Cover]

is this the only early printed book at the Peabody to have an older traveling companion. This volume of late medieval sermons, printed in 1493 in the town of Hagenow on the French-German border, contains two distinct collections, bearing separate title pages and indices, but completed a month apart. The printer may have hoped that the two would be bought as a set, and most are indeed bound this way: the Franciscan friars who owned it first covered it in thick leather, bleached with alum and decorated with stamps and other designs impressed by metal tools. [Image 4: Front Cover]

Looking inside, we find the remains of a third book, again a musical manuscript, one leaf being enough to cover the front and back boards of the book. The process of recycling leaves like these would continue for centuries, as use, damage, and (in newly-Protestant countries) religious change rendered these books unusable, obsolete, or potentially dangerous. But even if the writing had outlived its usefulness, there was no need to waste good material.

Not only does this practice give us a glimpse into the past lives of books and bookmakers, but in some cases we’ve been able to discover new pieces of texts (or even entire books) using what we now find in early bindings.

Yes, our apologies. We added his name to the top of the blog post once this was brought to our attention. Thank you!

Aha! Success:

Neil Weijer, Ph.D. and Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow in Premodern and Early Modern Studies at the Peabody Library

Who is the author of this very interesting piece? I tried to identify “nweijer” but have had no success thus far.