You may not recognize the name Laurence Hall Fowler, but you certainly know his work. As one of the preeminent architects at work in Baltimore during the first half of the 20th century, Fowler’s elegant eclecticism helped define many of the city’s most fashionable neighborhoods and important buildings. Although his work lives on, his name has faded from public consciousness. That’s where Amy Kimball comes in. As Materials Manager for Special Collections at the Sheridan Libraries, Kimball was introduced to Fowler through the Laurence Hall Fowler Collection, which the architect donated to the university (also his alma mater, class of 1898), upon his retirement in 1945. After more than 20 years of working with the collection, Kimball has emerged as a leading Fowler scholar, asking us to reconsider the contributions of this overlooked local master. On Wednesday, April 11, Kimball will present a talk titled “Light, Line, Iron, and Wood: Detail and Derivation in the Designs of Laurence Fowler.” The talk kicks off Evergreen Museum & Library’s annual House Beautiful lecture series, a trio of talks by experts in the fields of architecture and design. Each lecture is at 6:30 p.m. in the museum’s historic Bakst Theatre and followed by a reception with the speaker. Appropriately, this week’s lecture falls in the middle of National Architecture Week, and qualifies for AIA continuing education credit. In the following Q&A, Kimball offers a preview of tomorrow’s talk, explaining just how pervasive Fowler still is, why he might have chosen Baltimore over New York or Europe, and how his signature style remains elusive.

How did you first become interested in Laurence Hall Fowler? When I came to Hopkins, and came to Special Collections in 1996, Evergreen Museum & Library was part of my responsibility, and the collection lives here.

For those not familiar, what do you mean when you say “the collection?” The Laurence Hall Fowler Collection has complete sets of drawings for his commissions and the corresponding correspondence, documentation, specifications, and sometimes photographs. Besides that, we have two of his book collections: one is his rare books or treatises that he, as a book collector, accumulated. Then, we also have what you might call his reference library or his working library, the things he was using on the job that were more contemporary to his lifetime, as opposed to being rare treatises.

So, the collection was under your purview. That put it under your nose, but there are a lot of collections under your purview. What was it about this one that grabbed you? I was hired as the rare book assistant, so most of my job for most of my career here has been dealing with print material. So, it was kind of nice to have a chance to get into non-print material, and they’re beautiful drawings. Plus, I grew up in Towson in a historic house. I like old houses, but Fowler was never a name that had crossed my consciousness until I got to Hopkins.

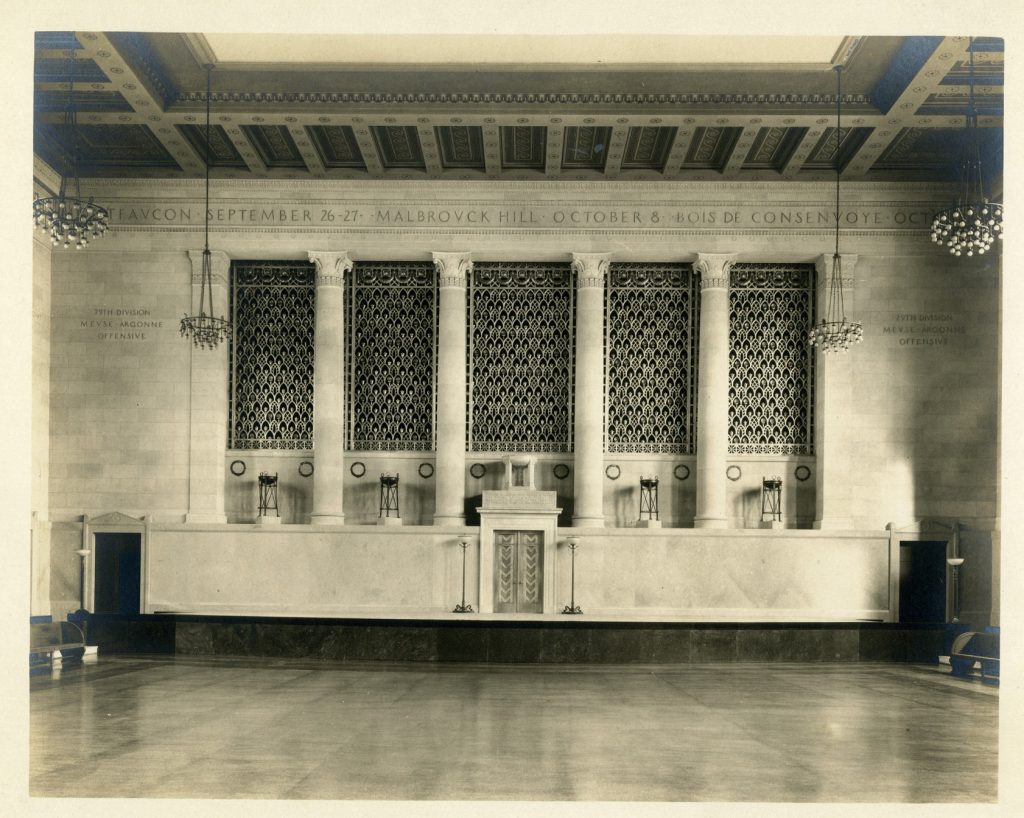

That’s probably true of most people, even though as Baltimoreans and Marylanders we interact with his buildings all the time. Can you enumerate some of the buildings he designed that we take for granted? Well, Evergreen was not his original design, but he certainly changed the look of it, so this room, the New Library, and the house’s John Work Garrett Libraries would not look the way they do without him. Same with the Bakst Theatre, which was a gymnasium before he renovated it in the early 1920s. Then there’s the War Memorial, across from City Hall in downtown Baltimore, and what was called the Annapolis Hall of Records (now part of St. John’s College). There’s also the Abel Wolman House across from the Homewood campus. It belongs to Johns Hopkins University. It’s currently used as a conference facility by the Department of Housing and Dining Services. Greenwood: that’s another house that people probably drive by. It’s on Charles Street in Towson. It’s now the Baltimore County Board of Education building. That was designed by Fowler for the Deford family and then it was part of Greenwood School.

What’s really interesting is that there are a lot of houses in Roland Park, Guilford and Homeland that were Fowler designs. And there are a number of historical houses that he had something to do with even though they weren’t his design. There’s Dumbarton—in present day Rodgers Forge—where he did alterations and additions. He also did some alterations to The Cloisters. They may not have been very major, but he had his hand in a lot of things and a lot of places.

His work is fairly ubiquitous, then. Why don’t we know him? I think one of the reasons he’s not as well known is because he was a very, very local architect, and though he did do a few things outside of Baltimore and outside of Maryland, it wasn’t a lot and they weren’t huge. He really was a homegrown boy who didn’t go too far.

Do you know why he decided to stay in Baltimore rather than go somewhere else and make more of a name for himself? After graduating from Hopkins with a bachelor’s degree in general studies with a focus on mathematics, he went on to attend Columbia University, where he earned a Bachelor of Science in the Course of Architecture in 1902. While he was at Columbia, he’d done a year or so with Boring and Tilton in their office, and he had worked with Bruce Price while he was getting his degree. During that time, his father had written to him and said, ‘This is wonderful, but you might consider being your own boss,’ and I think Baltimore probably just offered him that. He wanted to be in charge of what he was doing, though he was not a one-man show. He had a typical architectural office with draftsmen and chief designers and a secretary, especially after the War Memorial, when things kind of picked up. Also, he was an only child, so I think just the fact that his parents were here influenced his decision. His father died in 1911, so I think he had family obligations, and he knew the area. He was born in Catonsville and he loved Baltimore. He was really interested in Baltimore history and the conservation of that.

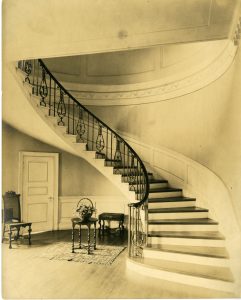

What are the hallmarks of a Fowler design? The thing that’s tricky about Fowler is he’s not Frank Lloyd Wright. You can’t just look at the house and say, ‘Oh, that’s Prairie Style. That must be Frank Lloyd Wright.’ Fowler’s design is very subtle and he’s using motifs and language that his peers are using. So, it’s difficult to stand in front of one of these homes in Guilford or Roland Park and say, automatically, ‘That’s a Fowler house!’ I find some commonalities. The barrel-vault ceiling he uses a lot—but he doesn’t have the trademark on that design, obviously—and a lot of curved lines that are not structurally necessary. It’s more about how he takes these elements that everyone is using and how he combines them.

Is it more about the feeling his spaces inspire than any particular design element? The homeowners that I’ve visited and talked with, that’s what they’ve conveyed to me. One of them had said, ‘We looked at a lot of houses. None of them felt quite right. We walked into this one and we felt like we were at home.’ Now you can’t really describe what makes it feel that way. So I think he was very sensitive to site—as much as the plot would allow him to be—and I think that has a lot to do with it. Like, how light is manipulated. It’s intangibles like that. I think it’s a byproduct of his decisions about where he places things.

When people come to the lecture, what do you hope they take away? I’m hoping to present some of those characteristics that folks can be on the lookout for, and just to place him in that world, in Baltimore in the early 20th century. I think he’s an important local architect. As we get further away from his lifetime we’re less likely to [remember him]. I think he deserves to have his name shouted a little bit.