By Rob Gamble, Processing Assistant and Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History

Part of a monthly series of posts highlighting uncovered items of note, and the archival process brought to bear on these items, as we preserve, arrange, and describe the Roland Park Company Archives.

Trolling through the Roland Park Company Archives, it is easy to become overwhelmed by the immensity of the collection. The company was fastidious in its recordkeeping, a reflection of the sweeping influence of ideas about modern business management in the first half of the twentieth century. (Some eras appear to have had employees better skilled at organizing their records than at other points in the company’s long history, but that discussion is for another time.) As one of the initial self-proclaimed “suburban” developments in America, Roland Park shaped the political, cultural, and architectural features that would come to be synonymous with suburbia. The collection, which I am currently helping to process in Special Collections, casts light on the wide range of social actors who helped define Roland Park.

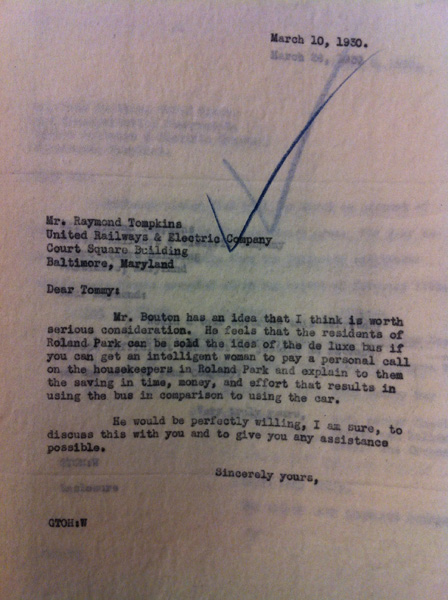

One of the wonderful things about collections of this magnitude (almost 500 cubic feet!) is happening upon the occasional document that, without knowing its immediate context, seems incongruous. For my inaugural blog post, I have selected such an artifact: a letter from the office of Edward H. Bouton, manager of the Roland Park Company, to Raymond Tompkins, vice president of the United Railways & Electric Company.

Written in early March 1930, the correspondence was one of thousands of documents that Bouton’s office transmitted annually. Details about landscaping features, rules for parking on the street, the architectural flourishes on individual houses, questions of jurisdiction over water pipes between Baltimore City and Roland Park (the former annexed the latter in 1918), reports taken from injured workers—such were matters of daily import in the company offices.

In this particular missive, Bouton, who had managed the company since its inception in 1893, tries to allay Tompkins’ fears about the inability of the newly introduced “de luxe bus” to attract Roland Park customers. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, suburban developments in America had been oriented around public transportation, particularly the street car. By 1930, despite the first rumblings of the global economic depression that would hamper growth for over a decade, suburban residents were becoming more reliant on automobiles. Even the Roland Park Company depended on motor vehicles for routine maintenance, as its folders of brochures for the latest models from the Packard Motor Car Company and others suggest.

United Railway long had held a close relationship to the Roland Park Company (note that Bouton refers to Tompkins as “Tommy”), having introduced its streetcars decades earlier. Bouton’s solution to low ridership was to harness the influence of Roland Park’s “housekeepers” to convince their husbands to ride the new buses and save “time, money, and effort.” Bouton undoubtedly recognized the significant role that housewives played in the day-to-day running of the neighborhood, such as paying or contesting bills, coordinating work to be done on their houses, and establishing associations like community kitchens.

Having read the latest books on modern advertising and written to their authors, like Northwestern University Professor Walter Dill Scott (who declined Bouton’s request for advice), Bouton sought “an intelligent woman” to persuade the housewives, someone with whom they might identify. Not exactly material for a new television drama, Mad Men of Upland Road, but this attention both to message and messenger illustrated the impact of evolving management and advertising techniques on the seventy-two year-old Bouton.

The success of Bouton’s experiment is not immediately known. While most correspondence in the collection was collated by the company, preserving the back-and-forth conversation over particular matters, this letter was not one of them. Perhaps Tompkins was unimpressed with Bouton’s suggestion, or perhaps the follow-up messages were filed elsewhere. In any case, even a letter three sentences long holds the power to illuminate many different historical issues, so long as we remain attentive to context.

There is a photograph of a railcar in Roland Park -the second photograph on this website: http://www.baltimorestreetcar.org/thirdcharm/thirdcharm.htm