“I see by your outfit that you are a cowboy.” The phrase comes from an old cowboy ballad, “ The Streets of Laredo,” also known as “The Cowboy’s Lament,” about a dying young ranch-hand shot in a bar fight. (At least, that seems to be the story; there are a lot of different versions of the song. You can listen to it along with some other cowboy tunes in this collection.)

The Streets of Laredo,” also known as “The Cowboy’s Lament,” about a dying young ranch-hand shot in a bar fight. (At least, that seems to be the story; there are a lot of different versions of the song. You can listen to it along with some other cowboy tunes in this collection.)

Cowboys have been dying for a long time—at least since the 1893 “frontier thesis” forwarded by Frederick Jackson Turner (who got his PhD from Hopkins) that put the frontier experience at the center of the distinctive American character… and posited at the same time that the American frontier was disappearing. “Buffalo Bill’s defunct,” e.e. cummings alleged in 1920.

But the cowboy is resuscitated just as often as he is declared dead: as an icon of the “Old West,” an emblem of “America,” a potent symbol of masculinity, a figure for social freedom, and a key player in arguments about the environment. Not to mention as an alluring image of smoking. We do seem to love our cowboys.

But the cowboy is resuscitated just as often as he is declared dead: as an icon of the “Old West,” an emblem of “America,” a potent symbol of masculinity, a figure for social freedom, and a key player in arguments about the environment. Not to mention as an alluring image of smoking. We do seem to love our cowboys.

You can get a sense of the cowboy’s many lives through his various appearances in print culture.

Just when Turner was sending out warnings of the demise of the Western frontier, Frederic Remington was celebrating all things Western in his sculptures and paintings. Pony Tracks (1895) is a  copiously illustrated anthology of some of his magazine articles about ranch life, stagecoach journeys, campfire stories—the whole cowboy kit and caboodle.

copiously illustrated anthology of some of his magazine articles about ranch life, stagecoach journeys, campfire stories—the whole cowboy kit and caboodle.

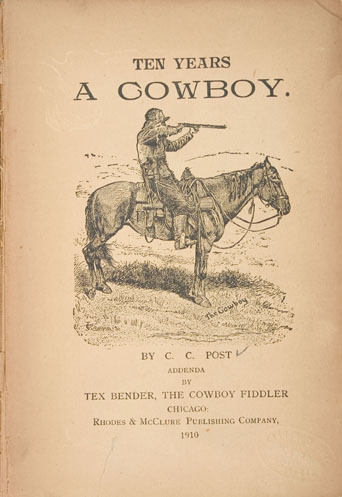

Of course, the cowboy mythology made for extremely popular entertainment, especially for city slickers and greenhorns. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show was one way the cowboy was repackaged as spectacle. Ten Years a Cowboy (1888) is evidence of another: the cowboy life as boy’s adventure story.

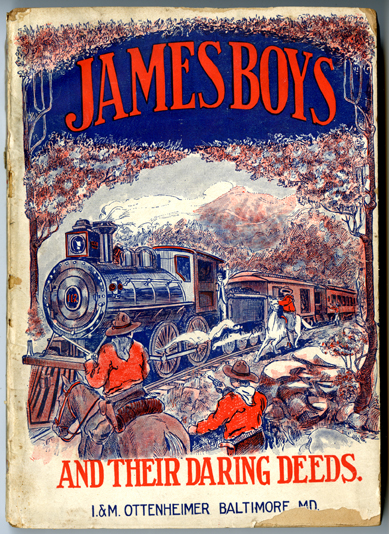

While cowboys originally worked as cowherds on horseback, the cowboy persona soon infiltrated other Western careers. In Randolph B. Marcy’s travel guide The Prairie Traveler, A Hand-book for Overland Expeditions (1861), the “frontier man” sounds an awful lot like a cowboy, with his experience as “a master spirit in the wilderness” (vi). And Jesse and Frank James, famous bank robbers, look pretty cowboy-esque on the cover of the sensational pulp “history” The James Boys’ Deeds of Daring (1911), turning a train hold-up into just one more Western exploit.

A Hand-book for Overland Expeditions (1861), the “frontier man” sounds an awful lot like a cowboy, with his experience as “a master spirit in the wilderness” (vi). And Jesse and Frank James, famous bank robbers, look pretty cowboy-esque on the cover of the sensational pulp “history” The James Boys’ Deeds of Daring (1911), turning a train hold-up into just one more Western exploit.

What about cowgirls, you ask? That’s a whole ‘nother fandango.