On this 77th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941), we glimpse back in time to the challenges facing librarians and university staff in preparation for war as reflected in meeting notes and correspondences from our archives. These documents summarize plans for protecting the various collections at Johns Hopkins University.

By the 1970s, some movie makers made light of the fear of invasion at the onset of WW2, but between 1939-41 reports of bombings in Britain and France struck fear in the hearts of U.S. civilians living along the east and west coasts. People were concerned that enemy planes would bomb coastal cities, and even more so that submarines would drop soldiers ashore to sabotage power plants and other key sites. Though the Imperial Japanese Navy, Kriegsmarine, and Luftwaffe were not equipped to carry out these attacks, university and city libraries along the east coast took precautions to protect their precious collections. Says Jim Stimpert, Senior Reference Archivist here in the Milton S. Eisenhower Special Collections:

By the 1970s, some movie makers made light of the fear of invasion at the onset of WW2, but between 1939-41 reports of bombings in Britain and France struck fear in the hearts of U.S. civilians living along the east and west coasts. People were concerned that enemy planes would bomb coastal cities, and even more so that submarines would drop soldiers ashore to sabotage power plants and other key sites. Though the Imperial Japanese Navy, Kriegsmarine, and Luftwaffe were not equipped to carry out these attacks, university and city libraries along the east coast took precautions to protect their precious collections. Says Jim Stimpert, Senior Reference Archivist here in the Milton S. Eisenhower Special Collections:

“The Kriegsmarine (German Navy) never built any aircraft carriers before or during the war, and land-based aircraft had nowhere near the range needed to make it from Europe to North America. The US ferried bombers to England in a succession of hops from Maine to Newfoundland to Greenland to Iceland to Ireland to Britain. That was possible because all of those locations were under allied control but the Germans did not have the advantage of airfields within range of North America. Even the V2 rocket did not have anywhere near the range needed to make it across the Atlantic. The Allies discovered after the war that the Germans were working on an early version of an ICBM , but it would have taken a couple more years before it would have been ready. They were certainly ahead of us in that respect. Our own missile program didn’t go anywhere until we got our hands on some captured V2 rockets (and Wernher von Braun).

Naturally, the Allies didn’t know for certain at the time that the Germans couldn’t fly across the Atlantic. That’s one of those little things that countries don’t disclose to their enemies during wartime. But we knew that if the Germans COULD have flown across the Atlantic and bombed North America, they likely would have done so. So it was more a matter of not knowing how close they were to perfecting that operation. Same with the atomic bomb; we knew they were also working on controlled fission but we didn’t know how close they were. After the war we learned they were not even close to building anything that could create a mushroom cloud.”

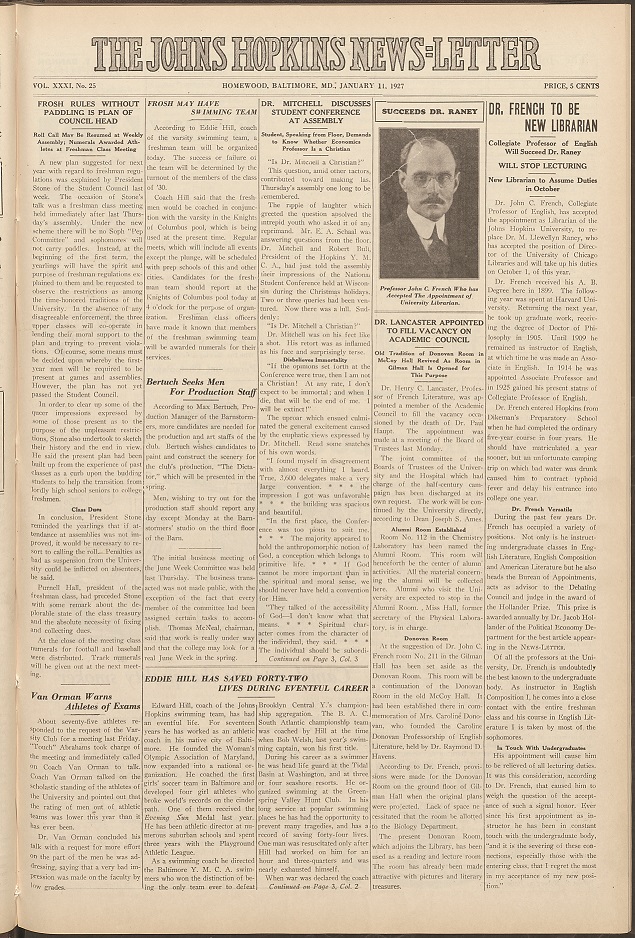

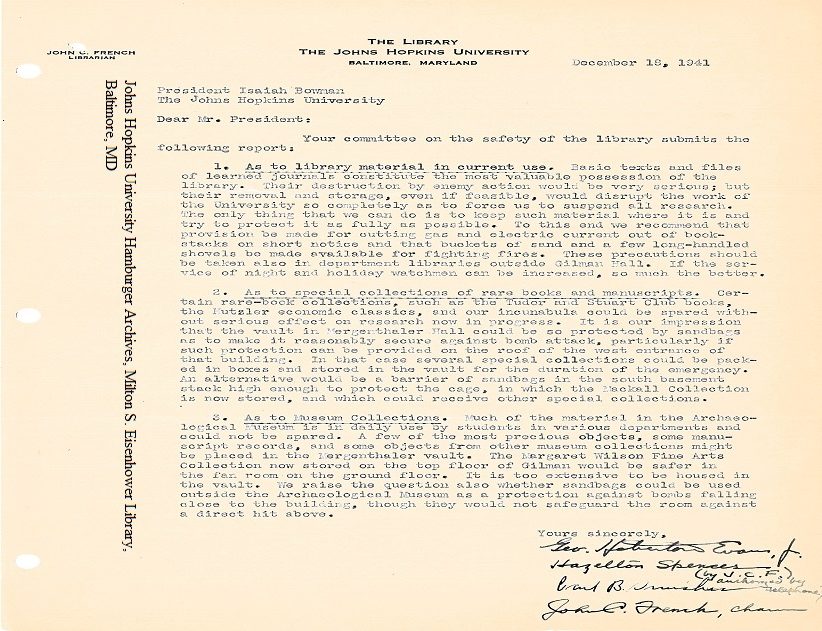

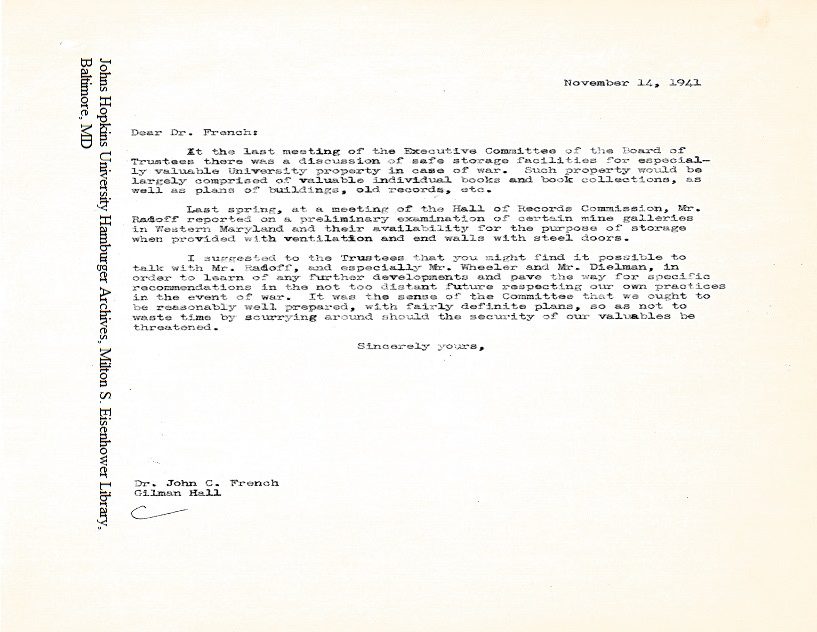

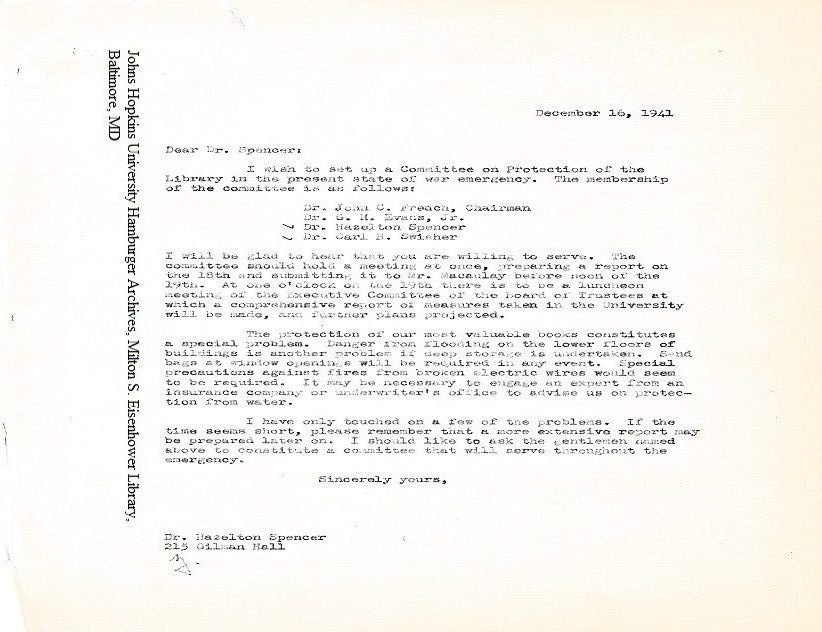

Johns Hopkins president Isaiah Bowman and the executive committee of the board of trustees commenced a plan of action to protect the Johns Hopkins University’s valuable books, book collections, building plans, old records, and museum artifacts. By the spring of 1941, the safekeeping of library valuables was at the forefront of the university’s agenda. One of the first steps was to establish a committee that would oversee the sheltering and, if necessary, offsite relocation of rare books and museum artifacts. The executive committee reached out to Dr. John C. French, university librarian, and three faculty members to form and oversee the Committee on the Protection of the Library. Their plan of action appears to have been two-fold: to utilize lower level campus buildings as deep storage vaults, and coal mines in case of a full-scale attack.

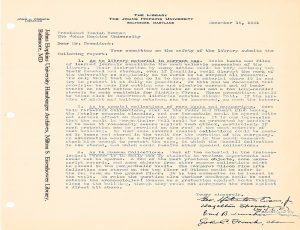

As stated in a December 18th report from French’s protection committee, students and faculty needed to continue their research and daily course work uninterrupted. Therefore in case of bombings, relocating basic books wasn’t feasible. Instead, books should remain in the stacks, but gas and power lines be severed and sand buckets placed throughout buildings to minimize the risk of fire. Rare books and manuscripts, however, were a different matter all together. The Tudor and Stuart Club books, Hutzler collection of economic classics, incunables, and museum items were to be placed in a vault in Mergenthaler Hall. It appears that at the time of French’s report to Bowman, some items had already been stored away, such as the Mackall Collection, and items from museum collections. The Margaret Wilson Fine Arts Collection would have to be moved from the top floor of Gilman Hall to the ground floor. However, if that were implemented, it could expose materials to the risk of flooding on lower floors. As a precaution, sandbags would have to be placed around the windows. One could only imagine that Gilman Hall would resemble a fortress more than an academic building.

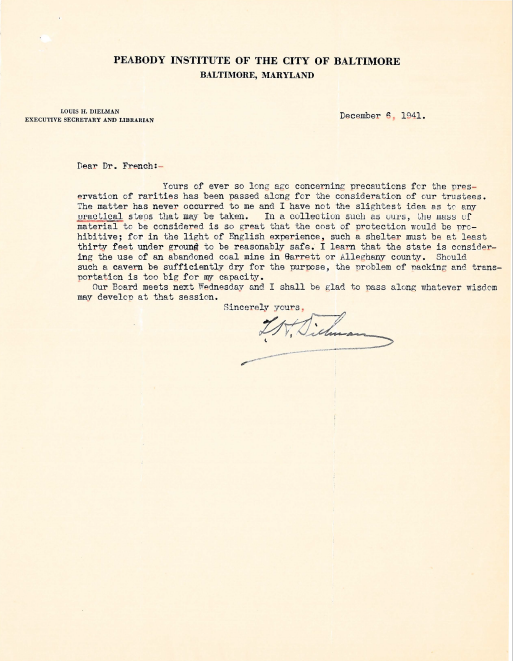

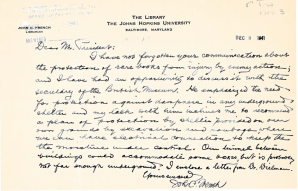

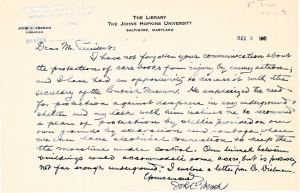

It appears that state of Maryland archivist Morris Radoff had been discussing with the university’s executive committee the feasibility of using mine galleries in Western Maryland to store items, but only under the consideration of adding proper ventilation and steel doors. Louis H. Dielman (executive secretary and librarian of the Peabody Institute) in his December 6th letter to Dr. French, reveals the locations of the mines: “…the state is considering the use of an abandoned coal mine in Garrett or Allegheny County.” Nevertheless, Dielman expresses that he has no idea how to handle the daunting task of moving the Peabody’s collections, and that such a feat would incur unimaginable costs. Specifically, he admits that he doesn’t have the expertise to advise on the packing and transportation of materials. It also appears that Dielman had been corresponding with a library in England about how to manage this kind of project, and it’s understandable why he would since London and its neighboring cities had just suffered the harrowing experience of The Blitz (September 1940-May 1941). In a letter just two days later, French mentions to Bowman that he has been communicating with the secretary of The British Library concerning how best to proceed with plans. Two months prior, architect Grosvenor Atterbury sent a letter to president Bowman dated October 1st saying he had a friend who possessed experience with safety vaults in both London and Spain, and that he could advise him on what to do. There’s also a reference of speaking with John Archibald Wheeler, theoretical physicist and Hopkins alum on how to proceed with relocating library collections.

It appears that state of Maryland archivist Morris Radoff had been discussing with the university’s executive committee the feasibility of using mine galleries in Western Maryland to store items, but only under the consideration of adding proper ventilation and steel doors. Louis H. Dielman (executive secretary and librarian of the Peabody Institute) in his December 6th letter to Dr. French, reveals the locations of the mines: “…the state is considering the use of an abandoned coal mine in Garrett or Allegheny County.” Nevertheless, Dielman expresses that he has no idea how to handle the daunting task of moving the Peabody’s collections, and that such a feat would incur unimaginable costs. Specifically, he admits that he doesn’t have the expertise to advise on the packing and transportation of materials. It also appears that Dielman had been corresponding with a library in England about how to manage this kind of project, and it’s understandable why he would since London and its neighboring cities had just suffered the harrowing experience of The Blitz (September 1940-May 1941). In a letter just two days later, French mentions to Bowman that he has been communicating with the secretary of The British Library concerning how best to proceed with plans. Two months prior, architect Grosvenor Atterbury sent a letter to president Bowman dated October 1st saying he had a friend who possessed experience with safety vaults in both London and Spain, and that he could advise him on what to do. There’s also a reference of speaking with John Archibald Wheeler, theoretical physicist and Hopkins alum on how to proceed with relocating library collections.

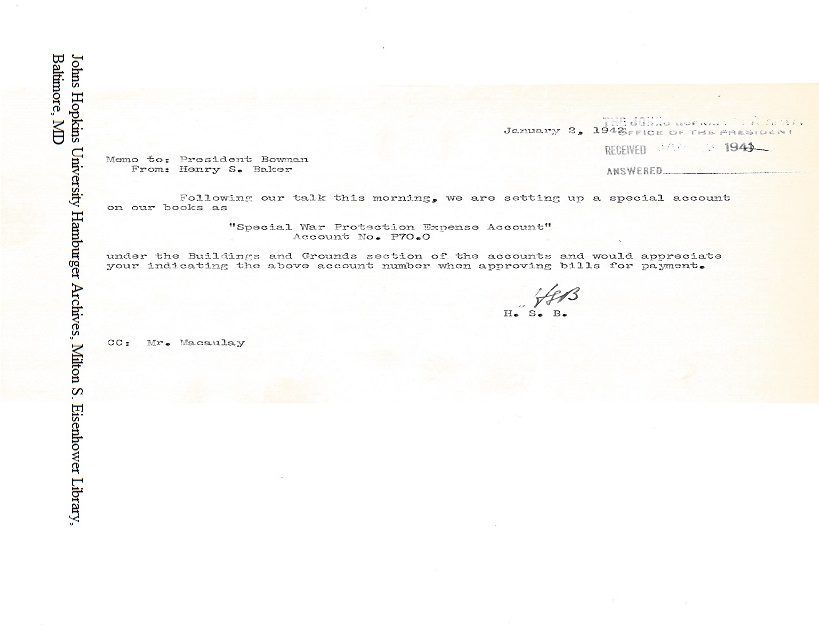

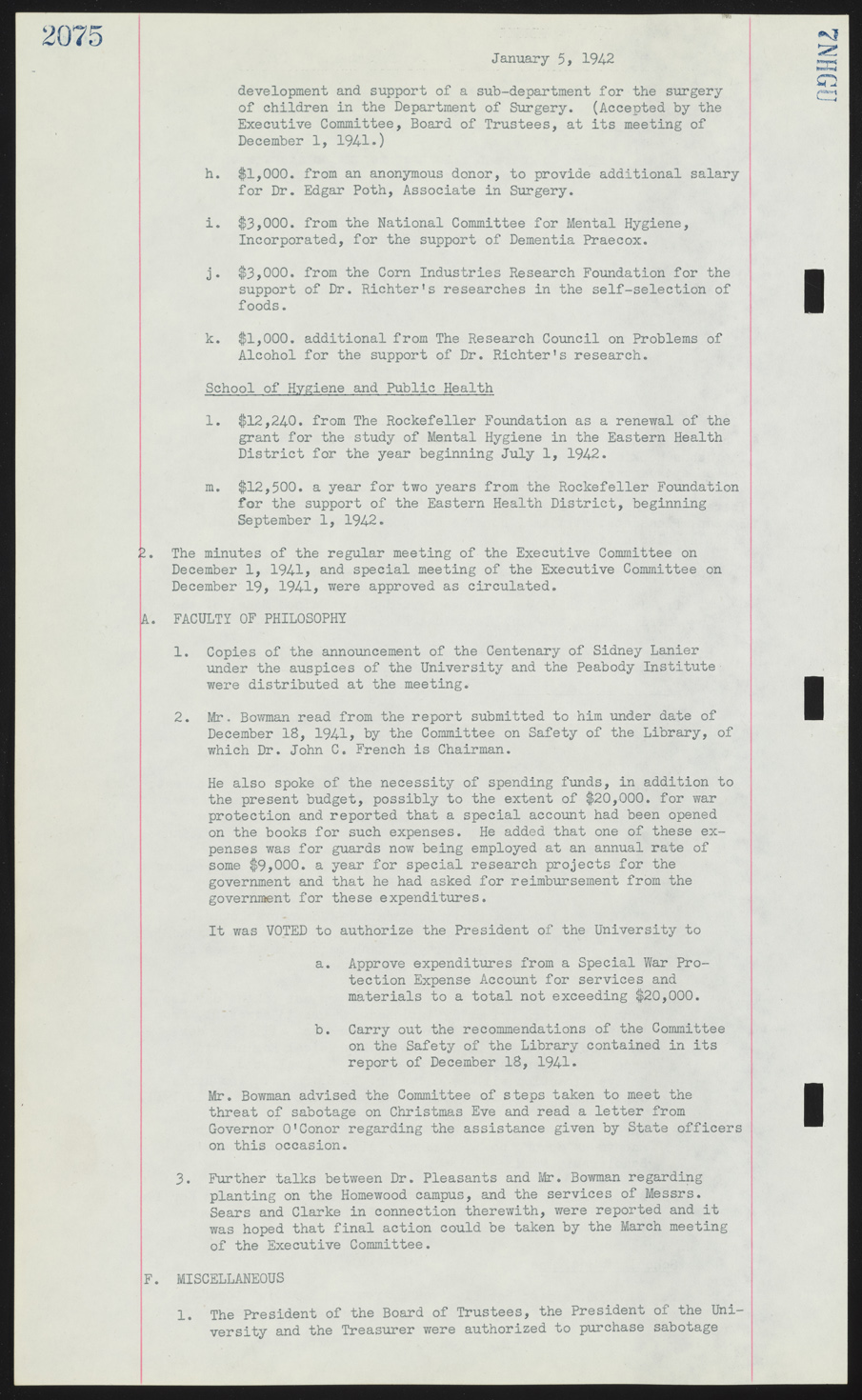

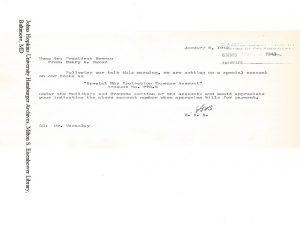

Just days away from Christmas, the executive committee discussed what they should do in case of sabotage on Christmas Eve. As seen in a copy of the December 19th meeting minutes, a request was made for increased watchmen during the holidays; during this time the U.S. Army had been conducting research at Hopkins. The university’s executive committee requested to set up a Special War Protection Expense Account to cover costs incurred, and put forth a request for the government to reimburse the additional cost of guards.

Just days away from Christmas, the executive committee discussed what they should do in case of sabotage on Christmas Eve. As seen in a copy of the December 19th meeting minutes, a request was made for increased watchmen during the holidays; during this time the U.S. Army had been conducting research at Hopkins. The university’s executive committee requested to set up a Special War Protection Expense Account to cover costs incurred, and put forth a request for the government to reimburse the additional cost of guards.

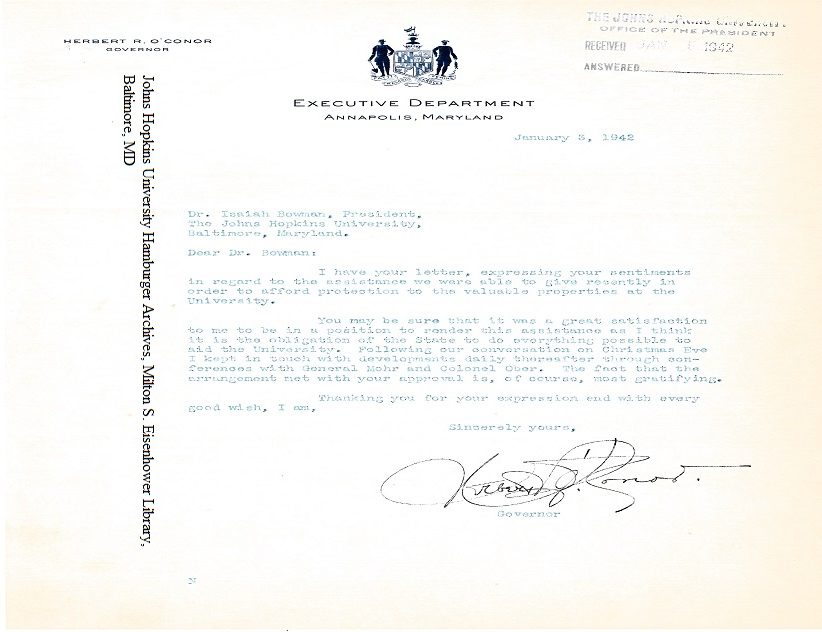

Less than a month after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the war expense account had been established by university treasurer Henry S. Baker, and the governor of Maryland had granted assistance to Johns Hopkins University.

Less than a month after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the war expense account had been established by university treasurer Henry S. Baker, and the governor of Maryland had granted assistance to Johns Hopkins University.

_____________________________

Thanks to Jim Stimpert, Sr. Reference Archivist for his contribution to this blog post.

All of the material in this post comes from the Records of the Board of Trustees, Record Group 01.001, series 2. The filename containing 11-41 is from the board meeting on November 3, 1941, and the file with 01-42 is from the meeting held on January 5, 1942.

You can read more on Hopkins’ preparation for war in 1941 in the JHU Gazette.