The post is guest-authored by senior Lucy Eills, a Writing Seminars major and curator of a new exhibition opening today on M-level of the Milton S. Eisenhower Library, the outcome of a Sheridan Libraries / Alexander Grass Humanities Institute Dean’s Undergraduate Research Award.

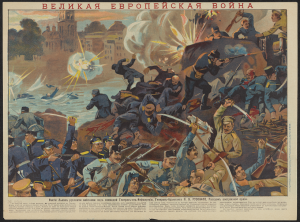

Over its four and a quarter years, World War I saw over 62 million troops enter combat. At its close on November 11, 1918, almost one hundred years ago, over 9 million troops and approximately 8 million civilians had been killed in the conflict. The magnitude of the war was unprecedented and its brutality was immense—impossible to describe. Nevertheless, soldiers, doctors, nurses, family members, and reporters attempted to do so. Driven to commemorate the dead and understand their own experiences, they often found their voices in poetry. In a new exhibit of rare books and archival materials that opens today in the Milton S. Eisenhower library, entitled “This book is not about heroes: Poetry and World War I,” I explore their efforts, contextualizing the wartime authors’ writings with information about, and pictures of, the war itself.

Poems form the core of this exhibit because of the unique way in which they became common across wartime experience. Those in combat and those outside of it, those who were wounded and those who cared for them, those who loved the fighting and those who hated it, all experienced war poetry in some way. Whether they were read, written, or shared in letters to loved ones, poems became an important language of the war, probing and recounting victory, defeat, injury, loss, camaraderie, grief, duty, and love.

Featured in the exhibit are books by well-known poets such as Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, as well as lesser known authors such as Vera Brittain and Andy Razaf. Their works are featured here in partnership with artifacts from wartime, including maps, photographs, a children’s game, and military booklets. Threaded throughout the exhibit is the correspondence of John G. Alexander, a Baltimorean and member of the American Expeditionary Forces, who fought on the western front through the November 11th Armistice. Here, Alexander’s letters are an intimate testament to the power of poetry in wartime as he quotes verse in letters to his wife, Alma, and reflects on their meanings.

Allied poetry during World War I changed alongside popular perceptions of and feelings about the war. Early on, verse was filled with patriotism and the strong desire to fight. In the exhibit, this mentality is exemplified by Rupert Brookes’ “The Soldier.” As the war dragged on, however, spirits and poetry began to reflect the harsh reality of wartime. World War I brought with it new technological advances never before seen on the battlefield, including destructive nerve agents and rapid-fire machine guns. Soldier-poets like Sassoon and Owen wrote unflinchingly about conditions on the front lines, as well as the ramifications of the war over the long term. Deaths, injuries, and post-traumatic stress disorder, then known as shell-shock, interrupted lives and livelihoods. So great was the impact that those killed became known as a “Lost Generation.”

Owen referenced this shift in perspectives in his “Preface” to a collection of poems. “This book is not about heroes,” he wrote, resisting the traditional ideal of the “war hero” in order to take a harder look at what patriotic young men were doing in the trenches—and how they were dying. Owen was killed in action not long after he compiled the collection, and his words come to us today through Sassoon, who published his work posthumously.

Owen referenced this shift in perspectives in his “Preface” to a collection of poems. “This book is not about heroes,” he wrote, resisting the traditional ideal of the “war hero” in order to take a harder look at what patriotic young men were doing in the trenches—and how they were dying. Owen was killed in action not long after he compiled the collection, and his words come to us today through Sassoon, who published his work posthumously.

It was not only combatants whose lives were shaped and changed by the war, and whose stories are reflected in the poetry of that time; non-combatants suffered as well. Families on the home front grieved when loved ones were killed or debilitatingly injured. On the front lines, medical volunteers, often women, were also killed and injured. During the war, many women took on jobs and responsibilities that had been the nearly exclusive domain of men—such as financial management and driving. After the war, when they were supposed to return to their previous roles, they sometimes found themselves at odds with social expectations. Brittain’s poem “Lament of the Demobilised,” exhibited here, explores her experience gaining autonomy in jobs on the front, and then finding it wrested away upon the war’s conclusion.

November 11, 1918, meant many things to many people. The conclusion of what was, at that point, the deadliest conflict in human history, was both an exuberant day and a somber one. People were killed up until the moment the ceasefire took place at 11 am. Through this exhibit, the many extraordinary sacrifices of the war are remembered, honored, and examined through poetry.