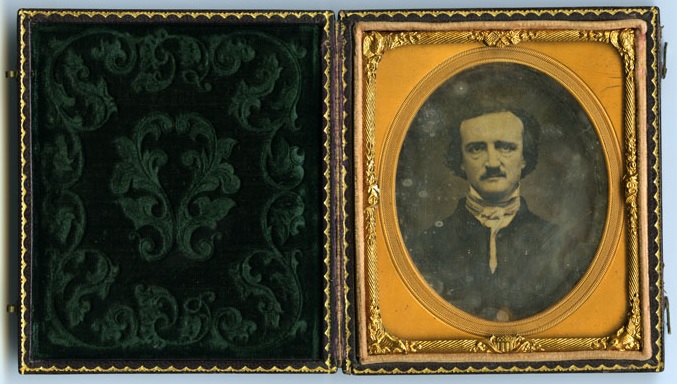

There are two days during the year when you are bound to come across some version of the portrait above: Halloween, when we gather about us anything spooky, ghostly, ghastly, or tragic; and the anniversary of Edgar Allan Poe’s birth in 1809, which is today.

The source of this well-known image is actually a daguerreotype, a single positive photograph made from a simple camera and “fixed” on a copper plate coated with silver. The daguerreotype process (named after Louis Daguerre, a French painter and master of the diorama, who perfected and announced the process in 1839) was the first to permanently capture photographic images.

Daguerreotype subjects had to remain motionless for several minutes while the primitive camera did its work, so people in these early photographs often look rigid, blurry, pained, or inert. Given the gloomy trend in the mid 1800s to commemorate dying elders and dead children in daguerreotypes–or even just sleeping children (often the only way to get them to stay still) in anticipation of possible death in an era of high child mortality–you would not be alone if you found these images to be, well, kind of creepy.

And there are additional fonts of creepiness to consider! Because of the silver coating on the plate, a daguerreotype has a mirrored surface–chances are you’ll see your own reflection within or on top of the photo. The coating is also fairly delicate and vulnerable to scratching. For this reason, nineteenth-century owners of daguerreotype portraits kept their precious pictures in small, velvet-lined, hinged cases, often with a memento related to the subject tucked inside. And if that memento were a newspaper obituary, or a lock of hair from a deceased loved one? The whole package becomes increasingly eerie.

So how does this context shape your response to the familiar, doleful image of Edgar Allan Poe? Knowing that the melancholy expression on his face and the discomfiture of his pose are somewhat characteristic of the photographic culture of the time, does Poe suddenly seem more typical and less… Poe-ish?

If the possibility of a typical Poe sends chills down your spine, let me offer you a few reassuringly odd tidbits. Rather than marvel at the distinctive mournfulness of the well-known Poe portrait, you can ponder the fantastic fate of the Poe daguerreotypes en masse.

As many as ten daguerreotype portraits were made of Poe in his lifetime. The one that is best known, often called the “Ultima Thule” image after poetic line by Poe, was taken in Providence, Rhode Island in 1848, a few days after Poe tried to commit suicide. (Needless to say, he was not looking his best.) For years, it was on display in Providence… but around 1860, it was lost or stolen. What we see above is a daguerreotype copy of the original daguerreotype. (Or rather, a copy I made of a digital reproduction of the daguerreotype copy.) And that daguerreotype copy was not the only one: at least five other copies of the 1848 daguerreotype were made… although one of these was also lost or stolen. Even stranger, of the other daguerreotype portraits made of Poe, many have also been lost or stolen. Two of these ten are gone forever–no copies were made, and their existence is known only through historical references. Another five of the original ten are also lost, but we can get a sense of them through photographic copies… some of which, again, have also been lost.

Confused yet? You can get a fuller and less bewildering account of the Poe daguerreotypes from this book by photographer Michael Deas. To make matters even stranger, Poe himself was one of the earliest commentators on the new daguerreotype invention–showing a characteristically acute understanding of the technology and its symbolic significance.

Of course, we must add to this story of image losses and copies the more recent creation of thousands, if not millions, of copies and recreations of Poe photographs. Poe tattoos, t-shirts, and tote bags abound; artists use the 1848 photograph as the basis for all kinds of Poe-rific riffs on melancholy, loneliness, and the infinite human appreciation for large black birds, as anyone knows who has searched google images for “Edgar Allan Poe.” For a more carefully curated collection of Poe images in contemporary times, check out this digital exhibition made by Hopkins students in the class “Edgar Allan Poe & His Afterlives.” They also made this timeline of major events in Poe’s life.

The history of Poe photographs is a hall of mirrors, full of disappearances, confounding origins, multiplication, and disorientation. And for Poe, that’s perfectly, uncannily appropriate.