by Alicia Puglionesi, PhD Recipient (History of Medicine) and former fellow, Special Collections Research Center

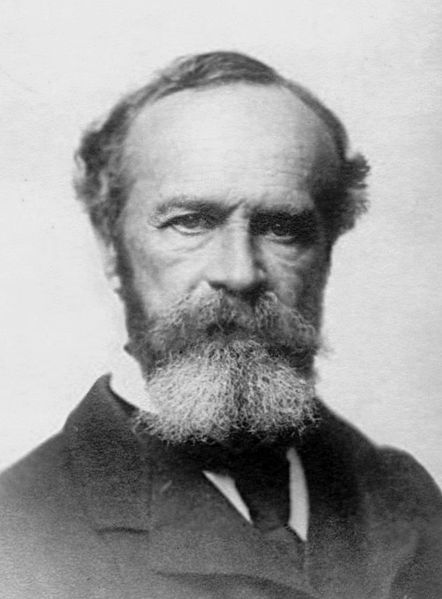

In Drawing and Believing, part 1, we met George Albert Smith, a British psychic medium, and the drawings that he supposedly produced using his telepathic powers. Those drawings would lead to a long argument between William James and Simon Newcomb on the subject of draftsmanship. James, often called the father of American psychology, and Newcomb, a driving force in American astronomy, were both prominent “men of science” and thus had the authority to weigh in on questions of general scientific and popular curiosity.

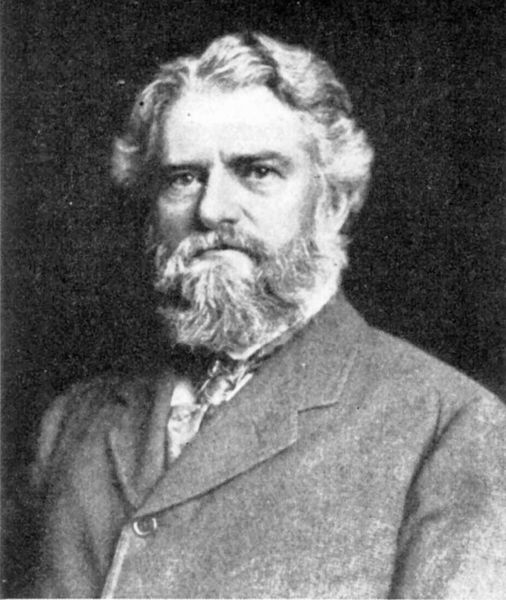

James organized the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR) in 1885, hoping to foster rigorous investigations of the psychic phenomena that were wildly popular in the late nineteenth century. Newcomb served as the Society’s first president. In his presidential address of January 12, 1886, Newcomb took a rather pessimistic stance not only on the Society’s accomplishments, but also on the veracity of psychic phenomena, especially telepathy (“the work of the society seems to me to have entirely removed any ground which might have existed for believing thought-transference a reality”).

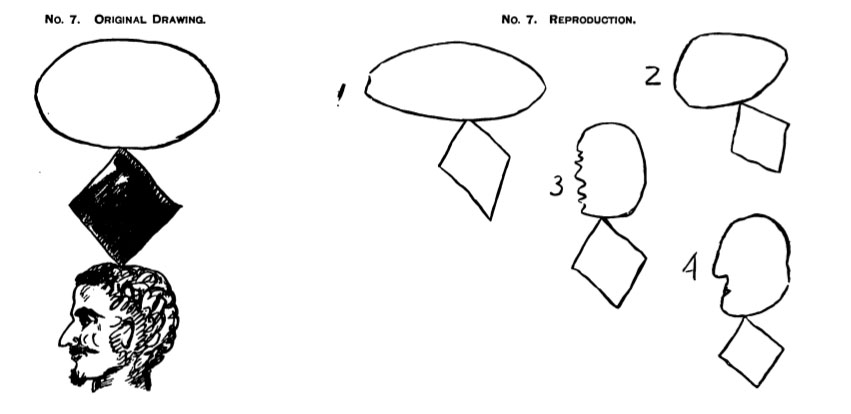

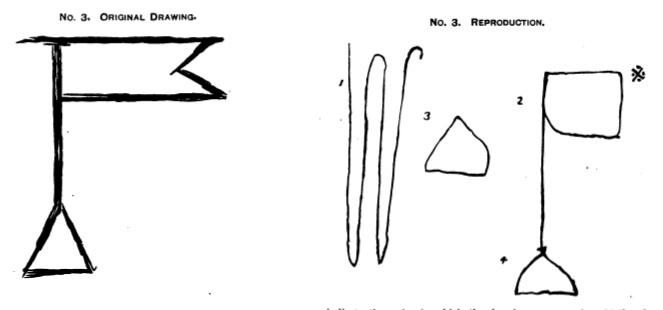

Among Newcomb’s targets in this speech was the George Albert Smith investigation, widely regarded as the best proof of thought-transference on record. Newcomb pointed out a slew of inconsistencies in the experiments. In tests supposedly performed while Smith was blindfolded, the lines of his drawings always met to form a closed image, which Newcomb deemed an impossibility without sight. Either the medium was cheating, or the experimenters were too lax.

Understandably concerned about the newly-formed ASPR running off the rails within its first year, William James defended the Smith drawings; the ensuing debate played out in the pages of the journal Science, and in private correspondence that survives in Newcomb’s papers at the Library of Congress. James challenged Newcomb to try blindfolded drawing for himself: “…he may perhaps be led to agree that [its] accuracy can hardly be deemed to fall outside the range attainable by the muscular sense alone. ”

Newcomb asserted that “I cannot make any such drawings,” but conceded that his poor drawing ability might be to blame. The very same day, William James took up his pencil, “and with tight-shut eyes scrawled the figures I enclose.” Unfortunately, James’s drawings have not survived in Newcomb’s papers; they were apparently very persuasive. Newcomb wrote back immediately to concede his point on the basis of James’s evidence. He agreed to strike out the passage criticizing the Smith experiments from the published text of his presidential address – in essence, revising the record so that his argument with James had never happened.

This would seem like a tactical victory for James, who had managed to salvage his best evidence for telepathy. Unfortunately, Smith, like so many other mediums, turned out to be a charlatan. In 1908 he would confess that all of his work with the SPR was completely fraudulent. The gentlemanly trust in images that led Newcomb to accept James’s blindfolded drawings, and James to accept Smith’s, would not, however, fall away in the face of treachery or new imaging technologies. The intuitive status of drawing as a form of communication that bypassed the distortions of language ensured a role for it in many subsequent attempts to access the inner workings of the mind, which I explore in my dissertation, The Astonishment of Experiment: Americans and Psychical Research, 1884-1935.

Sources:

- Editorial, “Comment and Criticism,” Science 7, no. 156 (January 29, 1886): 89–91. doi:10.2307/1760142.

- Gurney, et. al., “Third Report on Thought Transference,” Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, vol. 1 (1883):161-216.

- James, William. “Professor Newcomb’s Address Before the American Society for Psychical Research,” Science 7, no. 157 (February 5, 1886): 123. doi:10.2307/1761960.

- James, William. Letter to Simon Newcomb, February 12, 1886. Simon Newcomb Papers, Box 28, Library of Congress.

- James, William. Letter to Simon Newcomb, July 7, 1886. Simon Newcomb Papers, Box 28, Library of Congress.

- Newcomb, Simon, “Professor Newcomb’s Address Before the American Society for Psychical Research,” Science 7, no. 158 (February 12, 1886): 145–146. doi:10.2307/1760227.

- Newcomb, Simon. Letter to William James, February 16, 1886. Simon Newcomb Papers, Box 6, Library of Congress.