Part of a monthly series of posts highlighting uncovered items of note, and the archival process brought to bear on these items, as we preserve, arrange, and describe the Roland Park Company Archives.

This is Part 2 of the two-part post titled A Paper Database. Be sure to read Part 1 here!

So now it’s a time for a post that offers some very real and important insight into the Roland Park Company Records, and it’s information that I hope will aid researchers when they come to use the collection at the Sheridan Libraries. It’s also probably going to be a pretty long blog post, but you might thank me one day.

So let’s get straight to it: The vast majority of the RPC Records are correspondence files; they make up around 200 boxes worth of material. Normally, correspondence in archival collections is organized either alphabetically or chronologically or a combination of the two. Say they’re organized by year, and then organized by correspondent, so both chronological and alphabetical.

Well, if there’s one thing I can tell you that is simple and clear, it’s that the clerks at the Roland Park Company definitely organized things chronologically. That’s the good news! The bad news is that within each year they used a system that you probably haven’t seen before (with nuances that even I hadn’t seen before!).

Did you read my very first blog post? In it, I gave the example of one box that was described as both “Letters 662-970” and “General correspondence A-Z.” Well, A-Z makes sense, but what did 662-970 mean and how can it be the same thing?

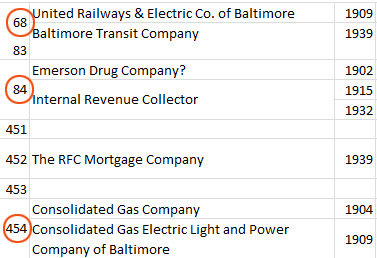

Well, it turns out that the clerks used a numerical filing system, which is a system where a concordance (a list of numbers like an index) is assigned to topics. So, say you filed all your credit cards under the number 5, all your tax returns under 10, and all letters from your cousin under 432. This doesn’t make sense on a personal scale, but it does make sense when a huge company corresponds with over 1,000 entities. So somewhere in the Roland Park office there was a list of almost 1,000 numbers, and each number represented a correspondent.

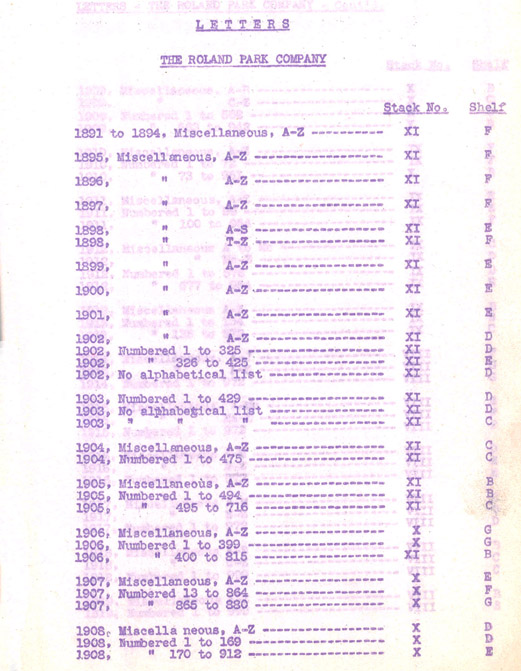

Here is an original finding aid for the collection (archivist nerd joy!), used by the clerks to find correspondence files in filing cabinets in their basement. You see that they started using this numerical system in 1902.

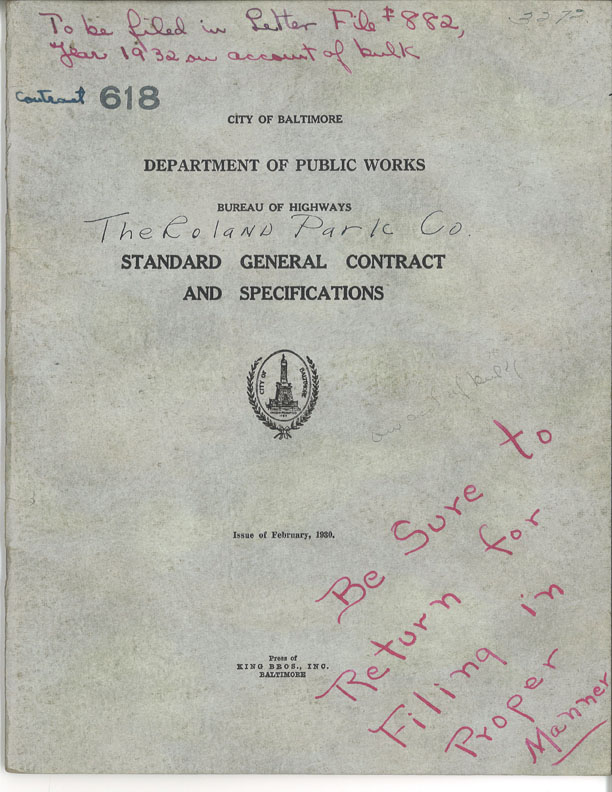

In the first half of this blog entry I talked about the importance of keys in relational databases; in other words, the important link between two kinds of information. In this case, there is [a numbered document], shown above, and an unknown [topic or correspondent]. The link/key between them is the number [882].

Are you ready for the really bad news? There is no key!! For whatever reason, the list of 1,000 numbers and what they mean did not survive, and so huge parts of the Roland Park Records are numbered, but we don’t know what those numbers mean! This paper database does not have a key! As a Real Life Information Professional, my suggestion is to panic!

So of course, some hope does exist. In trying to figure out this system I started a spreadsheet that attempts to re-create or de-code the numerical key. I didn’t come close to finishing, but more importantly I determined that the system is consistent and helpful once you figure it out.

So there remains one unanswered question: how can “Letters 662-970” and “General correspondence A-Z” be the same thing? The answer is that the Roland Park Company clerks filed correspondence first by year (chronologically), then by both number (numerical) and by letter (alphabetical). It kinda looks like this:

The numbers 1-100, filed A-Z. Then the numbers 101-200, filed A-Z, then 201-300, and on.

Confused? Don’t worry, you should be. But, I can promise future researchers that once you get elbow-deep in the files, and read the painfully long explanation of this system provided both here and in the finding aid, you will find that while complex, the numerical system really is dependable and useful.

Doesn’t this just make you appreciate real databases all the more?