Shana O’Connell (History of Art) is a graduate student in the Interdepartmental PhD program in Archaeology. Currently working on her dissertation in the cool confines of Special Collections she has spent less-temperate summers in the past traveling in Italy and Greece as well as excavating at Pompeii, Rome, and Southern Turkey. In the Spring of 2014 she will be teaching a Dean’s Fellowship Course entitled “The Disappearing Wall: Roman Frescoes in Context.”

A natural disaster, lost ancient Roman cities, excavations fraught with royal politics, treasures of art and daily life retrieved from dark, subterranean tunnels—these are just some of the highlights of the story of the rediscoveries of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Destroyed and buried in 79 CE by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, they were brought to light again by chance in 1753.

A natural disaster, lost ancient Roman cities, excavations fraught with royal politics, treasures of art and daily life retrieved from dark, subterranean tunnels—these are just some of the highlights of the story of the rediscoveries of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Destroyed and buried in 79 CE by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, they were brought to light again by chance in 1753.

Today, the Special Collections of the Sheridan and George Peabody libraries house a number of the artifacts from this monumental moment in the history of Archaeology. Coming in all shapes, sizes, and some with original bindings gold-edged or dust-worn, are books that were published to feed a European mania for all things Classical (fig. 1). Among them are the tomes of the Antichità di Ercolano (1755-1792), Jérôme-Charles Bellicard and Charles-Nicholas Cochin’s clandestine Observations sur les antiquités de la ville d’Herculanum (1755), and Sir William Gell and J.P.

Today, the Special Collections of the Sheridan and George Peabody libraries house a number of the artifacts from this monumental moment in the history of Archaeology. Coming in all shapes, sizes, and some with original bindings gold-edged or dust-worn, are books that were published to feed a European mania for all things Classical (fig. 1). Among them are the tomes of the Antichità di Ercolano (1755-1792), Jérôme-Charles Bellicard and Charles-Nicholas Cochin’s clandestine Observations sur les antiquités de la ville d’Herculanum (1755), and Sir William Gell and J.P.  Gandy’s Pompeiana (1817-1819). Whether these publications came with a royal stamp of approval or were printed behind the king’s back (he owned the ancient sites and the objects therein), they record not only the spectacular wealth of the ancient cities but they encapsulate an important moment in the origins of modern Archaeology. This era was the time when the material remains of Antiquity were valued not only as treasures of the past but also as objects of historical import, relics of a civilization that could be studied like the writings of Cicero or the poetry of Virgil.

Gandy’s Pompeiana (1817-1819). Whether these publications came with a royal stamp of approval or were printed behind the king’s back (he owned the ancient sites and the objects therein), they record not only the spectacular wealth of the ancient cities but they encapsulate an important moment in the origins of modern Archaeology. This era was the time when the material remains of Antiquity were valued not only as treasures of the past but also as objects of historical import, relics of a civilization that could be studied like the writings of Cicero or the poetry of Virgil.

My project this summer is to trace the history of a small but important artifact within the world left in the wake of Vesuvius: depictions of still life in Roman frescos. While the term “still life” seems straightforward enough and we have compositions that look strikingly familiar to those of later traditions of oil painting, the situation is more complex. The still lifes from Pompeii and Herculaneum were actually once

My project this summer is to trace the history of a small but important artifact within the world left in the wake of Vesuvius: depictions of still life in Roman frescos. While the term “still life” seems straightforward enough and we have compositions that look strikingly familiar to those of later traditions of oil painting, the situation is more complex. The still lifes from Pompeii and Herculaneum were actually once

part of architectural compositions—frescoes—that ornamented Roman houses and public

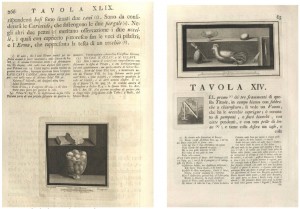

spaces (fig. 2-3). Not recognizing this fact of their design right away, the first excavators of the paintings removed sections of the walls, including the still lifes. They transported them in fragments for the private collection of the king, now the Museo Archeologico Nazionale of Naples. Thus many of the motifs in the wall paintings (fig. 3) came to be displayed like this: (fig. 4-5).

spaces (fig. 2-3). Not recognizing this fact of their design right away, the first excavators of the paintings removed sections of the walls, including the still lifes. They transported them in fragments for the private collection of the king, now the Museo Archeologico Nazionale of Naples. Thus many of the motifs in the wall paintings (fig. 3) came to be displayed like this: (fig. 4-5).

The illustrations of the Antichità and contemporary works housed in Special Collections at Hopkins offer a glimpse of the original appearance of the still lifes when they were newly rediscovered as well as valuable insight into the 18th and 19th century reception of these works. In this engraving of still lifes from a series of paintings at the Estate of Julia Felix in Pompeii we can observe great attention to detail as well as the imagination of the

The illustrations of the Antichità and contemporary works housed in Special Collections at Hopkins offer a glimpse of the original appearance of the still lifes when they were newly rediscovered as well as valuable insight into the 18th and 19th century reception of these works. In this engraving of still lifes from a series of paintings at the Estate of Julia Felix in Pompeii we can observe great attention to detail as well as the imagination of the  engraver (fig. 6). Like the Pompeian wall painter before him (fig. 7), he took care to illustrate the rich display of fruits through a large transparent glass bowl and added his own interpretation of the fruit bursting forth from a clay jar as a cluster of grapes. In the adjoining scene, set on a step, a pigeon freshly killed for a convivium (dinner-party), a garland, and a kylix (two-handled cup) filled with wine suggest a festive meal to come.

engraver (fig. 6). Like the Pompeian wall painter before him (fig. 7), he took care to illustrate the rich display of fruits through a large transparent glass bowl and added his own interpretation of the fruit bursting forth from a clay jar as a cluster of grapes. In the adjoining scene, set on a step, a pigeon freshly killed for a convivium (dinner-party), a garland, and a kylix (two-handled cup) filled with wine suggest a festive meal to come.

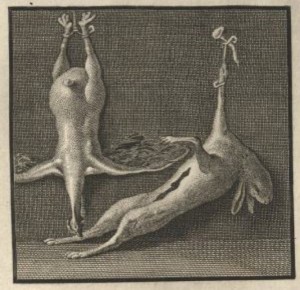

For these and other still lifes, the authors of the Antichità explain the significance of the subjects as images of food for the table. They also offer a learned commentary on the produce, the vessels, and the animals depicted in the scenes. The painting of game in one still life inspires them to quote the Roman poet Martial (1st century CE) on the gastronomic value of the lepus: “among four-legged ones, the finest is rabbit,” (fig. 8). Another bunny, this time live and nibbling on some grapes, is noted to have the same dusky color as a hare, an animal known by

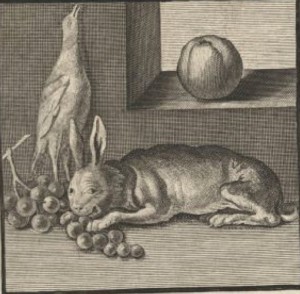

For these and other still lifes, the authors of the Antichità explain the significance of the subjects as images of food for the table. They also offer a learned commentary on the produce, the vessels, and the animals depicted in the scenes. The painting of game in one still life inspires them to quote the Roman poet Martial (1st century CE) on the gastronomic value of the lepus: “among four-legged ones, the finest is rabbit,” (fig. 8). Another bunny, this time live and nibbling on some grapes, is noted to have the same dusky color as a hare, an animal known by

the Greeks and Romans for its burrowing habits (fig. 9). According to several Roman authors that the authors cite, one of its Latin names, cuniculi, comes from the tunnels it so delighted in digging.

the Greeks and Romans for its burrowing habits (fig. 9). According to several Roman authors that the authors cite, one of its Latin names, cuniculi, comes from the tunnels it so delighted in digging.

In addition to discussing individual still lifes, book designers took advantage of the decorative potential of these motifs. Inspired by the actual fragments of fresco, still lifes  served as ornament at the beginning and ends of chapters (fig. 10-11), even the covers of books (fig. 1).

served as ornament at the beginning and ends of chapters (fig. 10-11), even the covers of books (fig. 1).

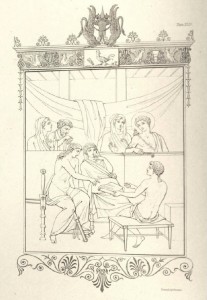

In the 1800’s Gell and Gandy’s publication went a step further. As the authors explain, images such as this frontispiece (fig. 12) were a composite of different motifs from Pompeian frescoes rather than an illustration of a single painting. In an image identified as “Poets Reading,” a still life of a rooster hangs in the frieze above the figures

(fig. 13). By re-combining the fragments of these frescoes, the engravers unwittingly re-enacted the original creation process of Roman wall painters who drew from many models

(fig. 13). By re-combining the fragments of these frescoes, the engravers unwittingly re-enacted the original creation process of Roman wall painters who drew from many models

to create their compositions (fig. 3). This time, however, the juxtapositions of architecture, figures, ornament, and still life were selected to a 19th century taste.

Certainly this lesson of selection remains with me as I make my own choices of digital reproductions of Roman still lifes for blog posts, dissertation chapters, and presentations alike!

Yeah, Shana! Interesting and entertaining! What a discovery! Art pulls us in in every. Century. A volcano starts everything over again in some cases. Good work! Love, Jane