by Alicia Puglionesi, Ph.D Candidate in the History of Medicine

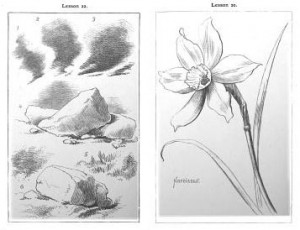

It was important to draw well in nineteenth-century America, at least if you hoped to appear cultured and refined. Drawing belonged to the set of impractical but socially-valuable skills cultivated in elite preparatory schools for men, and finishing schools for women, which also included singing, playing the piano, singing while playing the piano, and dancing while carrying on a witty conversation.

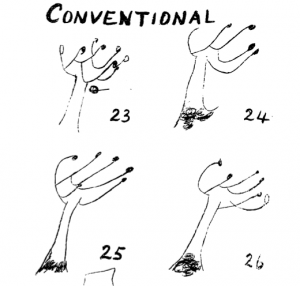

However, by the turn of the twentieth century, a different kind of drawing was catching the attention of researchers interested not in the rote techniques of a trained hand, but rather in the hidden contents of the mind. By paying attention to what children drew when they first entered school, before they received any instruction, pioneers of the new “child study” movement hoped to learn how children’s minds work, and what ideas they have about the world.

My dissertation project centers on the nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century science of psychical research. Psychical researchers hoped to determine whether “impressions from the minds of those about us [can reach] our own minds by channels distinct from those of the senses.” That is, they wanted to determine, scientifically, whether telepathy, clairvoyance, and spirit communication were real. So, how do we get from children’s drawings of trees to grown men who believe in telepathy? For me, it was the striking visual resemblance of their images that suggested a conceptual continuity. My research this summer, funded by the Special Collections Research Center Graduate Student Fellowship, has focused on the use of drawings as evidence in the study of the human mind and its capabilities.

The image on the right is from an investigation published in the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research in 1883. It is both evidence and illustration of the telepathic ability of one George Albert Smith, of Brighton, England. British investigators put Smith to the test by asking him to reproduce simple drawings shown to his partner Douglas Blackburn and then sealed in an opaque envelope; if Smith could “see” the drawings in Blackburn’s mind, he could fairly claim telepathic powers.

This evidence proved less than ironclad, however, when subject to the scrutiny of American scientists who had signed on to the psychical research project at the urging of William James. These scientists – astronomers, mathematicians, geologists, and chemists – prided themselves on taking a more rigorous stance towards psychical phenomena than their credulous British counterparts.

In Part 2, a debate between William James and the astronomer Simon Newcomb boils down to a question of drawing ability.