“For Love or Mo ney: Art, Commerce & Stephen Crane” is about the work of Stephen Crane, boy wonder of the 1890’s literary world. On display at the George Peabody Library through June 14, the exhibition features quite a few phenomenal objects in humble disguises. Maggie: A Girl of the Streets is one of those objects… in more ways than one.

ney: Art, Commerce & Stephen Crane” is about the work of Stephen Crane, boy wonder of the 1890’s literary world. On display at the George Peabody Library through June 14, the exhibition features quite a few phenomenal objects in humble disguises. Maggie: A Girl of the Streets is one of those objects… in more ways than one.

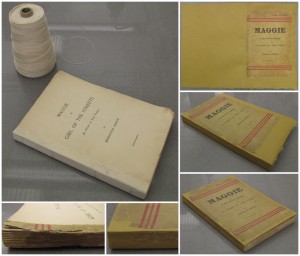

You may have read about Maggie in a previous blog post. Written when Crane was just 21, Maggie is the story of a poor city girl who, friendless and desperate, turns to prostitution to survive. In 1893, no respectable publisher would risk his reputation on such a book. So Crane paid an unknown publisher to print the book, using his own very limited funds. (This publisher did not even put his name in the book, so grave was his concern about its contents — and even Crane used a pseudonym.) As you can imagine, these circumstances did not lend themselves to the production of a durable, handsome object. Maggie was printed on cheap paper with a cheap paper cover and a staple binding.

Fast forward 120 years: this modest little paperback is now incredibly rare, precisely because of its lowly origins. Crane couldn’t afford to print that many copies; initially seen as a failure, few copies of the novella were preserved. Those that did survive into the twentieth century degraded over time. Combine its scarcity with its eventual rediscovery as a key text of late nineteenth-century American literature — not to mention the fact that our copy features an inscription by Crane on the cover — and voilà, you’ve got a very special book, albeit one that looks… rather shabby. The Sheridan Libraries’ copy of 1893 Maggie is about as desperate as Maggie herself: faded, fragile, falling apart.

How to display such a delicate object? Enter the conservator.

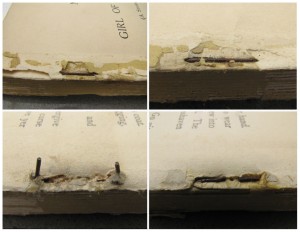

Usually it’s the job of a conservator to try to save as much as is possible of the original structure and materials of an artifact. However, sometimes, like with Maggie, something about the original is causing damage. As mentioned above, Maggie has no sewing to hold her together – just two (now rusty) steel staples and some (now brittle) animal glue on the spine. This not only made it tricky to open the book fully, it also led to stress points at the covers such that the back cover was lost and the front cover was fully detached – with first and last pages at risk of being not too far behind.

It also turns out that this is not the first time that Maggie has encountered a “restoration” treatment. Noticing that the bottom half of the last page of the text was missing, someone kindly found another copy of Maggie, took a Photostat image of the missing half of the last page, and used it to fill in the lost piece. Unfortunately, it was left as a negative image – white text on a photographic silver-based black background. The rigidity of the photographic paper was also pulling and damaging the much softer wood pulp paper of the rest of Maggie.

The conservation of Maggie therefore looked something like this:

1) Carefully lifting what was left of Maggie’s spine and front cover, the book was taken apart, and each page surface cleaned with erasers to remove surface dirt.

2) As for the old Photostat repair, it was Photoshop to the rescue! Taking a high resolution scan of the Photostat, using color inversion and a bit of touch-up in the software, and then using pigment-based inks printed on Japanese paper of sympathetic weight and color, it was possible to create a more subtle and suitable repair page.

3) Paper repairs were performed where necessary (using Japanese tissues and wheat starch paste adhesive), and then Maggie’s textblock was put back together – this time by sewing with a chain stitch. This is a very inconspicuous type of sewing that will allow the aesthetics of Maggie to stay the same (flat back), but give her full “openability” – relieving the stresses that the staples were causing.

4) To repair her paper covers (being very careful to test the stability of the Stephen Crane inscription!), Maggie’s remaining front cover was washed, deacidified and then lined onto a mustard-colored Japanese Matsuo Kozo paper, leaving enough space to make the back cover out of this same piece of paper.

5) Putting Maggie all back together, the top edge of the new cover was trimmed to align with the top of the textblock and attached to the textblock. The remaining edges were trimmed AFTER the cover was in place – just to make sure everything lined up. Finally, the pieces of Maggie’s original spine that were saved were adhered in place.

So after her trip to the conservation lab, Maggie is all ready for exhibition and use! Back in one piece, stable for handling, and aesthetically looking a lot like when she was first published. Of course… if you look closely, you can see exactly where all her repairs are. After all, the guidelines for conduct and code of ethics to which conservators adhere say that “Any intervention to compensate for loss should be documented in treatment records and reports and should be detectable by common examination methods.” But I won’t tell if you don’t – the full story will be kept safe in her conservation documentation, just in case anyone wants to know exactly what happened to Maggie on her trip to the “book doctor.”