How do you become a professional writer? It helps to have a family member provide a model—or better yet, both parents and a couple of siblings. It also helps to have access to a good public library—and to read voraciously, across genres, nationalities, and styles. And if you can get a part-time job at a newspaper, that’s a great springboard. These are the tricks of the trade that helped launch the career of Stephen Crane, a fabulous yet under-rated American story-teller.

How do you become a professional writer? It helps to have a family member provide a model—or better yet, both parents and a couple of siblings. It also helps to have access to a good public library—and to read voraciously, across genres, nationalities, and styles. And if you can get a part-time job at a newspaper, that’s a great springboard. These are the tricks of the trade that helped launch the career of Stephen Crane, a fabulous yet under-rated American story-teller.

Some other tips from Crane: you might try flunking out of college, twice; self-publishing a novel on the most shocking subject you can think of; living in a disgusting boarding-house with a bunch of medical students; disguising yourself as a homeless man in order to research a story… what? This isn’t what they teach in the Writing Sems?

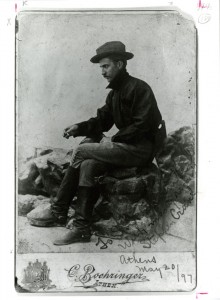

You can learn more about Crane’s, um, unconventional approach to the writing life in the new exhibition For Love or Money: Art, Commerce & Stephen Crane, at the George Peabody Library in Mt. Vernon, which offers an unusual first-hand look at rare books, letters, photographs, and newspaper clippings documenting Crane’s literary output. The exhibition runs through June 14 and is free.

You can learn more about Crane’s, um, unconventional approach to the writing life in the new exhibition For Love or Money: Art, Commerce & Stephen Crane, at the George Peabody Library in Mt. Vernon, which offers an unusual first-hand look at rare books, letters, photographs, and newspaper clippings documenting Crane’s literary output. The exhibition runs through June 14 and is free.

Crane got his first break as a teen-age journalist, writing up cultural events and fashion notes from the seaside resorts of New Jersey for New York newspapers. Not exactly Jersey Shore… but not entirely different. After the afore-mentioned aborted stint at college, he moved to New York and hung out with the city’s growing underclass: the denizens of saloons, flophouses, brothels, and tenements—the casualties of a nation dealing with a huge influx of immigrants and rapid industrialization. He got paid a few cents a word for his articles and stories about the urban poor—never quite enough to earn a decent living, but more than he would have gotten a decade or so earlier. He was able to scrape by because the newspapers and magazines that published his work were struggling to adapt to a new technological landscape (advances in printing machinery), new consumers (a lot of those immigrants were becoming literate) and increased competition. It was the time of “yellow journalism” and the great newspaper wars, when the New York World (owned by Joseph Pulitzer) and the New York Journal (owned by William Randolph Hearst) threw all kinds of juicy material at potential readers—political scandal, personal tragedy, celebrity gossip, sensational fiction—in the effort to attract customers.

Sure, Crane needed to sell his work, but he was also dedicated to what he called “the beautiful war” for truthful art; he wanted to write stories about real people dealing with real problems—which were often ugly or scary or sad. At the age of 21, he finished his first long work, a novella he called Maggie: A Girl of the Streets. (And yes, if “a girl of the streets” sounds salacious to you, you’re on the right track.) He couldn’t get a trade publisher to print Maggie because it was too risqué. So he used up a small inheritance and borrowed money from his brother to print it himself. He still couldn’t get anyone to buy it, however, so he tried his hand at guerilla marketing: he paid a couple of guys to sit on the elevated railways—the precursors to the subway—reading Maggie in full view of the crowd.

After the Maggie letdown, Crane was ready to write a potboiler. Perusing old copies of The Century Magazine, which ran a series on Civil War generals and battles, he decided to write a novel of the Civil War from a soldier’s point of view. But in the end, he couldn’t make himself color inside the stereotypic lines. The book that he produced is an utterly unique, vivid recreation of war from the perspective of a combatant. War from this angle isn’t a picture-perfect stage for glorious acts of heroism; it’s a messy roller-coaster ride of smoke, fear, bravery, pain, noise, solidarity and most of all, confusion. Ironically, Stephen Crane—who was born six years after the Civil War ended—had never seen military action. But even Civil War veterans were convinced by the story’s realism.

Watch this space for more about Crane’s break-through novel The Red Badge of Courage—and additional installments on the vicissitudes of the literary life, circa 1895.