By now, most of us have heard the news that the venerable Encyclopaedia Britannica will no longer produce a printed set. For those among us who remember leafing through the volumes of colorful images and arcane text, and for intellectual history in general, this is somewhat sad. This is a book that has been printed for 244 years, and besides, we discovered some incredible bits of information that way.

no longer produce a printed set. For those among us who remember leafing through the volumes of colorful images and arcane text, and for intellectual history in general, this is somewhat sad. This is a book that has been printed for 244 years, and besides, we discovered some incredible bits of information that way.

Before we shout “The King is dead! Long live the King!” and turn online for encyclopedia-type information, let’s pause and look back at a long history of encyclopedias, many of them archived here in the Sheridan Libraries.

The desire to have all of the world’s knowledge in one place is as old as history itself. From the Great Library of Alexandria to something called the World Wide Web, we have sought ways to accomplish this goal. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the dream took the form of a book, or a set of books, as various encyclopedia projects took shape, the most famous being the French Encyclopédie. At first, an attempt to translate the English Cyclopaedia of Ephraim Chalmers, the Encyclopédie grew into a mammoth printed enterprise, with 17 volumes of text and 11 volumes of exquisite engraved plates. Its editors, including Diderot, spent years gathering articles on all areas of knowledge, both practical and philosophical.

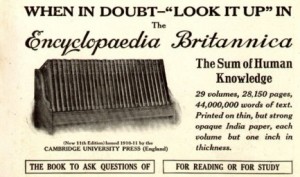

The Encyclopaedia Britannica was part of this 18th century movement to publish all the world’s knowledge. First printed in 1768, when the Encyclopédie was still putting out its volumes, it took its place beside grandiose projects in other countries. Germany had already finished the Zedler Lexikon (1732); its 64 volumes are available to you in the George Peabody Library. And England had inspired the French project with Chambers’ Cyclopaedia in 1728.

The history of the world’s encyclopedias is a fascinating one, as it traces our quest for finding all knowledge in one place; an impossible dream, but obviously one that hasn’t died with the advent of the digital age. We can mourn the disappearance of the venerable Britannica, but we can continue to study and use the old printed sets, as well as forge optimistically ahead into the digital era.

Yearning for more? Explore the holdings in historic encyclopedias here at the Sheridan Libraries.

I just love posts like this! You BET that humankind has always wanted the world’s knowledge in one place, and that goes backward *and* forward — most science fiction stories have a “library computer” or something that will access anything from anywhere. (My absolute favorite is the museum’s system in Mike Resnick’s “Ivory,” a stunning and beautiful tale about a researcher and his mysterious client.) I treasure my volumes of the Encyclopedia Americana’s yearbook from the ’60s, which sum up the entire year. Encyclopedias will live forever, in all of their formats and languages! Thanks again for this marvelous post.