Veterans Day, as you may know, used to be called Armistice Day; November 11 was officially designated such by President Woodrow Wilson in 1919 to honor the cessation of hostilities on that day the previous year. The same day was set aside as Remembrance Day in Commonwealth countries by King George V. November 11 is also a national patriotic holiday in France and Belgium. Germans observe a national day of mourning, the Volkstrauertag, on the Sunday closest to 16 November—not to mark the official armistice but to commemorate all victims of war.

Veterans Day, as you may know, used to be called Armistice Day; November 11 was officially designated such by President Woodrow Wilson in 1919 to honor the cessation of hostilities on that day the previous year. The same day was set aside as Remembrance Day in Commonwealth countries by King George V. November 11 is also a national patriotic holiday in France and Belgium. Germans observe a national day of mourning, the Volkstrauertag, on the Sunday closest to 16 November—not to mark the official armistice but to commemorate all victims of war.

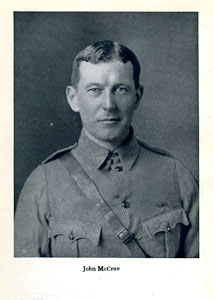

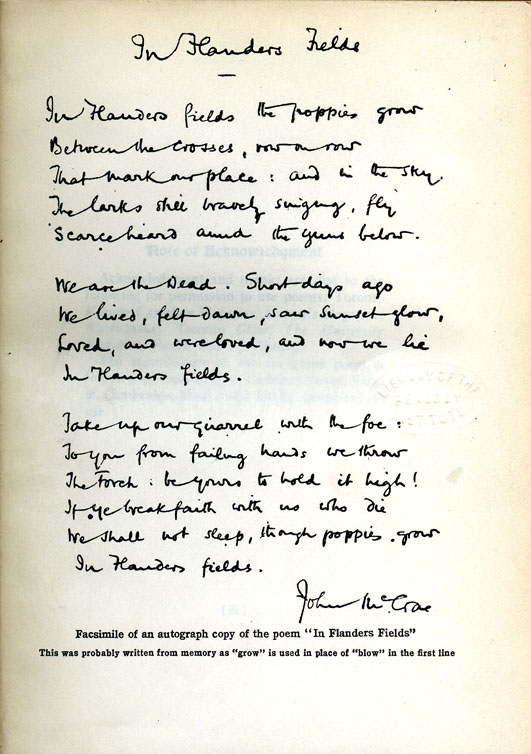

The name and nature of Armistice Day in the U.S. changed in 1954 to include veterans of later wars. But there continues to be an international “Great War” quality to Veterans Day; if you’ve ever been handed a tiny red paper poppy on November 11, you know what I mean. The poppy as a symbol for the war comes from the poem “In Flanders Fields” by the Canadian physician and officer John McCrae, who died of pneumonia in 1918 while commanding the Canadian military hospital in Boulogne. “Flanders,” the region that is part of present-day Belgium, France and the Netherlands, is closely associated with the battles of Ypres, Passchendaele and the Somme; the poem is often recited for November 11 commemorative ceremonies in Canada, the U.K. and the U.S. In its international origins and popularity, “In Flanders Fields” represents the global scale of the war.

The name and nature of Armistice Day in the U.S. changed in 1954 to include veterans of later wars. But there continues to be an international “Great War” quality to Veterans Day; if you’ve ever been handed a tiny red paper poppy on November 11, you know what I mean. The poppy as a symbol for the war comes from the poem “In Flanders Fields” by the Canadian physician and officer John McCrae, who died of pneumonia in 1918 while commanding the Canadian military hospital in Boulogne. “Flanders,” the region that is part of present-day Belgium, France and the Netherlands, is closely associated with the battles of Ypres, Passchendaele and the Somme; the poem is often recited for November 11 commemorative ceremonies in Canada, the U.K. and the U.S. In its international origins and popularity, “In Flanders Fields” represents the global scale of the war.

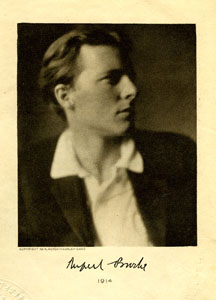

“In Flanders Fields” may be the most widely known poem of the First World War, but it has a few rivals. One would certainly be “The Soldier” by Rupert Brooke, who died in 1915 from sepsis from an infected mosquite bite on his way to Gallipoli. Another contender: “Dulce et Decorum Est” by Wilfred Owen. For those who object to McCrae’s not-so-subtle call to arms and Brooke’s patriotic invocation of an “English heaven,” “Dulce et Decorum Est” presents war as painful, ugly and haunting. Owen’s soldiers limp through the mud, exhausted, wounded, drowning in the green glow of poison gas. “In Flanders Fields” is a roundeau and has been turned into a song; in contrast, the rhyme in “Dulce et Decorum Est” proceeds like a heavy footstep. Owen himself died one week before the armistice, shot in the head as he led an attack on enemy strongholds near Joncourt, France.

“In Flanders Fields” may be the most widely known poem of the First World War, but it has a few rivals. One would certainly be “The Soldier” by Rupert Brooke, who died in 1915 from sepsis from an infected mosquite bite on his way to Gallipoli. Another contender: “Dulce et Decorum Est” by Wilfred Owen. For those who object to McCrae’s not-so-subtle call to arms and Brooke’s patriotic invocation of an “English heaven,” “Dulce et Decorum Est” presents war as painful, ugly and haunting. Owen’s soldiers limp through the mud, exhausted, wounded, drowning in the green glow of poison gas. “In Flanders Fields” is a roundeau and has been turned into a song; in contrast, the rhyme in “Dulce et Decorum Est” proceeds like a heavy footstep. Owen himself died one week before the armistice, shot in the head as he led an attack on enemy strongholds near Joncourt, France.

Owen’s work came to attention through the mediation of Siegfried Sassoon; the two men met at the Craiglockhart War Hospital, where both were being treated for shell shock. Sassoon started out in the glorifying vein, like Brooke and McCrae, but his war experiences soon led him to a more cynical view. The sonnet “Dreamers” and the almost-sonnet “Survivors,” for example, are dressed in proper rhyme and meter but pack a mean punch: a quick, gut-wrenching insight into the soldier’s broken psyche. One of the few “war poets” to survive the war, Sassoon lived long enough to write on other subjects—but still had nightmares in late life about the horrors of the trenches.

Owen’s work came to attention through the mediation of Siegfried Sassoon; the two men met at the Craiglockhart War Hospital, where both were being treated for shell shock. Sassoon started out in the glorifying vein, like Brooke and McCrae, but his war experiences soon led him to a more cynical view. The sonnet “Dreamers” and the almost-sonnet “Survivors,” for example, are dressed in proper rhyme and meter but pack a mean punch: a quick, gut-wrenching insight into the soldier’s broken psyche. One of the few “war poets” to survive the war, Sassoon lived long enough to write on other subjects—but still had nightmares in late life about the horrors of the trenches.

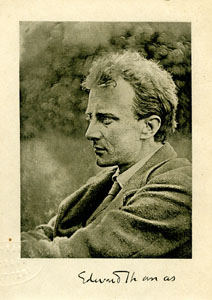

Other poets of the Great War include Edward Thomas, author of “In Memoriam [Easter 1915],” Alan Seeger, Isaac Rosenberg, Robert Graves and Vera Brittain. Selections from their works, plus biographies, images, oral histories, film clips and other documents from the war, have been collected in The First World War Poetry Digital Archive.

Other poets of the Great War include Edward Thomas, author of “In Memoriam [Easter 1915],” Alan Seeger, Isaac Rosenberg, Robert Graves and Vera Brittain. Selections from their works, plus biographies, images, oral histories, film clips and other documents from the war, have been collected in The First World War Poetry Digital Archive.

Was the poetic outpouring of the First World War typical of later wars? What else did “war poets” write about? How did war change poetic conventions? If you have questions about the poetry of the Great War, ask them of an expert in person! Edna Longley, author of Poetry in the Wars and editor of The Annotated Collected Poems of Edward Thomas, will give the Turnbull Lecture tonight at 6:30 pm in Mudd Hall Auditorium.

I concur with Sue. Thanks for posting this very informative and moving post. I knew so little about the poetry of the Great War–I had mostly read prose like “Im Westen nichts neues”, but this made me feel like reading a lot more.

Thank you!

Dr. Dean, This is a glorious and beautiful post. You have woven WWI poetry into a single, meaningful story. “Flanders” is so sad, and it will never lose its meaning. Thanks for the incredible amount of work it must have taken to put this post together.